Vul. Horbachevskoho, 18 – university building ID: 1485

This was the first student dormitory in Lviv, built in 1894-1895 as an example of a grassroots initiative, a common cause of many people, especially the Society of Fraternal Aid organized by the Polytechnic students. Its detailed history illustrates the process of building a house in the city in the late 19th century. Now the lecture-rooms of the Institute of Entrepreneurship and Advanced Technologies of the Lviv Polytechnic National University are located there.

Story

Today it is common for universities to have student dormitories, which are built and maintained primarily by educational institutions themselves. More than a hundred years ago, however, students mostly lived in rented apartments or, more frequently, rooms, the so-called "stations." Instead of paying rent (or part of it), they often were engaged in tutoring the children of the apartment owners. This concerned not only university students but also gymnasium and secondary school students, since in the 19th century, educational institutions were not ubiquitous and operated only in a few towns of the region. Newspapers were full of advertisements about the search for "stations", while topics related to moving to the town and this type of housing were quite common in fiction.

In his essay Science as a Vocation sociologist Max Weber points out that two groups of people have always been interested in the number of students. The first one includes so-called Privatdozenten, associate professors in the German academia who received fees not from the university but from students; while the second consists of house and apartment owners, who can rent their rooms out (Weber, 1918). Although Weber apparently meant chiefly small towns in Germany (such as Marburg, Heidelberg, etc.), whose life revolved primarily around universities, the role of this aspect should not be underestimated for larger cities, such as Lviv.

In the late 19th century, Lviv actually became the city of two universities, as well as one academy (veterinary), two secondary schools, and five gymnasiums (nine by 1914). It was in the 1880s and 1890s that the city grew rapidly and experienced a construction boom. The issue of housing for students had also become more acute.

In 1888, at a meeting of the Fraternal Aid Society, organized by the Polytechnic School students and aimed at supporting poor students, it was decided to undertake the construction of a house for students. A committee was then elected from among the Society, although its members later changed several times. Complicating matters was the fact that the students did not have models to follow (the fact is emphasized in their history in 1897, see Księga pamiątkowa, 1897), so actually they were about to set a precedent. In 1890, the committee was headed by Karol Rolle, a chemistry student, the future president of Krakow; in late 1891 – early 1892, by Józef Sosnowski, a future architect; in 1893, by Alfred Zachariewicz, son of the rector and a future architect.

This was a grassroots initiative, implemented by activists, and the official structures did not take part in it. Students enlisted all possible help. The first monetary donations were made in 1890, and a year later official permission from the governor to raise funds was received. Students involved their professors, sent letters to local administrations (municipal, county, etc.), to famous and influential people. Many politicians and their wives can be found on the list of the Fraternal Aid Society benefactors, including count Włodzimierz Dzieduszycki, governors Agenor Gołuchowski and Alfred Potocki; religious figures, such as Fr. Wasyl Focjewicz and Archbishop Issakowicz; entrepreneurs, such as the Wczelak brothers, Zygmunt Rucker, the Mikolasch family, philanthropist Maurycy Lazarus, writer Kornel Ujejski, as well as numerous professors and graduates of the Polytechnic.

Professor Julian Zachariewicz and Ivan Levynskyi (Jan Lewiński) donated a plot of land for the future house as part of their Kastelówka project on present-day vul. Horbachevskoho, not far from the Polytechnic building. Eventually, the Fraternal Aid invested 10,000 ducats of their own funds and thus became the owner of the future House of Technicians, although this had not been plannedoriginally. In the future, to implement the project, they took loans from a bank, as well as looked for manufacturers, who were ready to give some products at a discount or as a gift.

In 1894, several events, important for technicians, were held simultaneously. As the construction of the General Provincial Exhibition was being completed, construction materials and labor became cheaper, which they took advantage of. The cornerstone of the building was laid on July 12, 1894, in the midst of the exhibition, this becoming the final event of the Third Congress of Polish Technicians (July 8–11) and the Congress of the Alumni of the Polytechnic.

In May 1894, the committee announced an architectural competition, with June 20 as the deadline for applications. Only students were allowed to apply. Among five projects, the work of Jakób Kuraś, the future head of the Przemyśl magistrate construction department, won. The jury consisted of Professors Gustaw Bisanz (architecture) and Placyd Dziwiński (mathematics), as well as Tadeusz Münnich (professor at the School of Art and Industry), Ludwik Baldwin-Ramułt, an architect, and Karol Ruebenbauer, engineering student, the then chairman of the Fraternal Aid Society.

Jakób Kuraś finalized the project in accordance with the remarks of Michał Łużecki (then an assistant to Julian Zachariewicz at the Department of Architecture), as well as a specially selected Technical Commission for the construction of the House of Technicians. Kuraś led the construction (he was a so-called inscipient); apart from that, he was advised by architect Tadeusz Mostowski (in 1893, an assistant to Gustaw Bisanz at the department). Ferdynand Gisman, an engineering student, was the construction administrator, while the aforementioned chairman of the Society, Karol Ruebenbauer, was the "leader of the whole action."

On August 25, earthworks were started: leveling of the ground, under the guidance of Maksymilian Huber, a future professor and then an engineering student, with the participation of Adam Lewicki, an assistant professor of geodesy, and assistant Paul (first name unknown). On October 9, they received the magistrate's permit for the construction. A room was rented for a low fee in a nearby villa for the construction "office." Although the address is unknown, it was one of the Kastelówka villas, which still belonged to Ivan Levynskyi at that time. By the end of the year, the three-storey house was built. In the following year, finishing works continued in the interior. The solemn opening of the building took place on November 24, 1895.

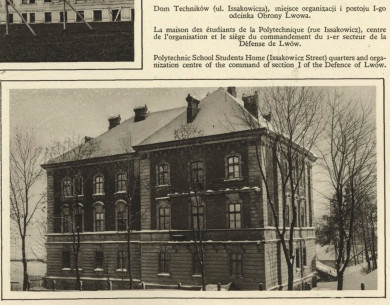

An important part of the House history is the already mentioned cornerstone consecration, which took place on July 12, 1894. It was conducted by Eustachy Skrochowski, a Roman Catholic priest. His participation was not accidental, as he had once studied at the Technical Academy and only later chose the church. An activist during the Spring of Nations in 1848 in Lviv, Skrochowski belonged to the Resurrectionist Congregation (pol. Zgromadzenie Zmartwychwstańców); he was known for his involvement in secular affairs and participated in the preparation of the General Provincial Exhibition in 1894, in particular, the art pavilion; at the same time, he was elected president of the Polytechnic Alumni Congress (Sanak, 2016). The consecration of the completed House was carried out by the Armenian Catholic Archbishop Isak Issakowicz, apparently due to the untimely death of Skrochowski. The street, where the House of Technicians was erected, officially laid in 1895, was named after Issakowicz (Kurjer Lwowski, 1895, No. 178, p. 4).

The completed three-storey building had modern technical equipment, sewerage, electric lighting, telephone, a freight lift, bathrooms, as well as a laundry and a kitchen. The rooms were mainly designed for one (15), two (6), or three (3) students; there was a block of three toilets on each floor and a bathroom with showers in the basement. In addition to these rooms, there was an event room on the second floor with a reading room next door and an administration room; each floor had a room for servants. Entertainment was also provided, in particular, a billiard table was purchased for the House, and a bowling alley was set up in the area behind the house. It is known from the press that in winter the students used to arrange a skating rink on the ponds of the neighboring Marjonówka, a recreation complex around the ponds, which is called Medyk today (Kurjer Lwowski, 1898, No. 358, p. 5).

On October 5, 1895, the magistrate gave permission to use the house, the first students settling in on October 15. At that time, only men could study at the Polytechnic, so all the protagonists of this story are male: students, professors, architects, builders and the House staff, including five boys and a caretaker. Regarding the rules of use of the house, a special statute (pol. Regulamin) was developed; the House was managed by the Society representatives. The first to manage it were Karol Ruebenbauer and his deputy Jan Łaurynow, as well as a treasurer and two other members of the Fraternal Aid. The manager lived in the House for free on the second floor.

The House of Technicians was setting the pace in Lviv: as early as the 1890s, similar initiatives were launched at the Franz I University, which resulted in the Ukrainian Academic House in 1904 (vul. Kotsiubynskoho 22), the Polish Adam Mickiewicz Academic House (vul. Stetska 7) in 1907, the Polish-Jewish Andrzej Potocki House in 1912 (vul. Yosyfa Slipoho), and the Jewish House (vul. Anhelovycha) in 1913. At the same time, the question of the construction of the Second House of Technicians arosein 1906; however, the house itself was built later, in the interwar period.

In 1918, the House of Technicians, under the leadership of Ludwik Wasilewski, became one of the centers of Polish forces during the Polish-Ukrainian war.

During the interwar period, the building was expanded by adding a fourth floor, the open brickwork façades were plastered and repainted, and the roof was replaced completely. Since that time, the appearance of the house has changed little. It was redesigned inside for educational purposes; after Ukraine became independent, the roof was rebuilt again, with the walls raised.

Architecture

The house was built on the territory of Kastelówka, designed by Julian Zachariewicz and Ivan Levynskyi, on the edge, on the newly opened ul. Issakowicza (nowvul. Horbachevskoho), next to the recreation complex known as Marionówka (now Medyk). The location is really convenient for the dormitory, as it is very close to the Polytechnic buildings and,at the same time, on the outskirts of the city (as of the late 19th century), which was considered extremely healthy. The villa of Zachariewicz was situated nearby; in the early 20th century, quite a lot of the Polytechnic professors (Antoni Popiel, Gustaw Bisanz, Roman Zalozetskyi (Załoziecki) and others) settled in villas around the House of Technicians.

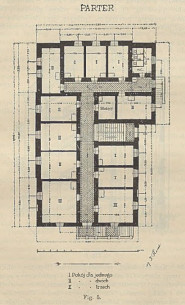

The house with a building area of 468 m2 was erected at a distance of 6 m from the street. The site was lined with trees, a well was dug in the north of the site, a wooden dump was arranged, and a drain pump was installed in the south. The house is rectangular in planand has an avant-coprps;its internal layout is based on a system of corridors. The house faces the street with its shorter side, where the main entrance is made through the stairs leading to a small veranda. The premises are arranged on both sides of a long corridor, which turns sideways;in the avant-corps, there is an additional, back entrance; next to it, there is a block of bathrooms. The staircase is located near the northern façade; next to it, there is a room for a service worker. Four rooms on the floor face north, three rooms face west, five rooms face south. On the second floor, instead of three rooms with windows facing south, there was an assembly room for student events, and next to it, a room for the administrator of the House of Technicians.

Initially, there were three floors with apartments for 1, 2 or 3 students. However, it was immediately thought that in each of the rooms it was possible to accommodate one person more than planned. In the high basement, there were storerooms and a kitchen, a dining room, a room for the caretaker and guard, as well as a bath and a shower, a laundry.

"The whole house is in the Renaissance style": that's how its design was interpreted by the authors of the history of the Fraternal Aid Society (Księga pamiątkowa, 1897). Its details, such as trimming of the windows and pediments, the rustication of the ground floor walls surface and the house corners on the higher floors, really fit this definition. At the same time, the asymmetrical composition of the façades, open brickwork, attics and massive balconies (which have not been preserved), as well as a brick non-order cornice can be seen as grounds to interpret the building's style as a kind of picturesque historicism, which combines elements of different historical styles and varying colorful building materials.

The symbols of the Society are preserved on the main façade. The trimming and pediment above the balcony door, above the main entrance, contain a pair of compasses and a triangle, surrounded by bay leaves like the symbols of the Polytechnic Society. This element was originally made of terracotta; today it is apparently just painted over.

In the interwar period, a fourth floor was added to the house, it was plastered and repainted, attics and masonry balconies disappeared. The roof was raised again later. Although the house has generally retained a lot of its original appearance, its overal image has been virtually lost.

Related buildings and spaces

Organizations

Sources

- Księga pamiątkowa Towarzystwa "Bratniej Pomocy" Słuchaczów Politechniki we Lwowie, (Lwów, 1897)

- Album inżynierów i techników w Polsce, t. I, cz. II. Towarzystwo bratniej pomocy studentów Politechniki Lwowskiej, (Lwów, 1932)

- "Rada m. Lwowa", Kurjer Lwowski, 1895, Nr. 178, s. 4

- "Dom politechników we Lwowie", Dodatek do nr. 328 Kurjera Lwowskiego, 1895, s. 1

- “Ze stowarzyszeń”, Kurjer Lwowski, 1898, Nr. 358, s. 5

- "Nekrologia", Czasopismo techniczne, 1917, Nr. 16, s. 168

- Program dla ces. król. Szkoły Politechnicznej we Lwowie na rok naukowy 1893/1894

- Program dla ces. król. Szkoły Politechnicznej we Lwowie na rok naukowy 1894/1895

- Marcin Sanak, "Ksiądz Eustachy Skrochowski (1843–1895) jako badacz starożytności chrześcijańskiej", Starożytność chrześcijańska. Materiały zebrane, red. Józef Cezary Kałużny, t. 4, (Kraków, 2016), s. 117–150

- Max Weber, Science as a Vocation, translation from: 'Wissenschaft als Beruf,' Gesammlte Aufsaetze zur Wissenschaftslehre (Tubingen, 1922), pp. 524‐55.