Ukrainian Summer Courses, 1904 ID: 69

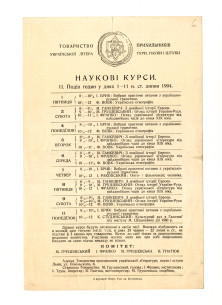

From June 23 to July 22, 1904, the summer courses took place in the Belle Vue Hotel at ul. Karla Ludwika 27 (now prosp. Svobody). They were organized for the residents of Galicia and Ukrainians from the Russian Empire. From the organizers' point of view, the courses were to show the need to open an independent Ukrainian university in Lviv (Гнатюк, 1904).

Story

It was the Society of Supporters of Ukrainian Science, Literature and Art that was formally responsible for organizing the courses. The founders of the Society were Ivan Franko, Volodymyr Hnatyuk, Mykhailo Hrushevskyi and artist Ivan Trush. The aim of the society was to organize events, which were impossible or problematic for the Shevchenko Scientific Society (hereinafter NTSh) for internal reasons (Rohde, 2019). Apart from the founding members, one of the organizers of these courses was Maria Hrushevska, Mykhailo Hrushevskyi's wife. All the lecturers at the courses, except Mykola Hankevych, were full members of the NTSh. According to the official data, the total number of students taking these courses was 135 people from all over Galicia and Dnieper Ukraine (Грушевський, 1904). It should also be emphasized that the idea of these courses did not come from the scholars themselves but from the Ukrainian community (Дорошенко, 1930).Mykhailo Hrushevskyi gave a review course on the history of Ukraine-Rus, Ivan Franko — on the history of Ukrainian literature, Fedir Vovk — on Ukrainian anthropology and ethnology, Kyrylo Studynskyi told about the cultural and educational movement in Galicia, from Markiyan Shashkevych to 1860, Mykola Hankevych told about the history of Western Europe since the French Revolution. Ivan Rakovskyi's seminar on human ontogenesis and phylogenesis was the only course in natural sciences; however, it was closely related to Vovk's course on anthropology. Stepan Tomashivskyi prepared lectures on Hungarian Rus and the history of Ukrainian-Polish relations in the 17th century. Hist style of lecturing was considered extremely boring, therefore his second session was barely attended and the further sessions cancelled. In addition, Ivan Bryk, a young philologist, gave a course on the Ukrainian language, with the main emphasis on grammar; this course was aimed primarily at Ukrainian students from the Russian Empire, who did not have the opportunity of a systematic, advanced training in Ukrainian. Mykhailo Hrushevskyi described the essence of these courses as "historical Ukrainian studies," whose main components were history, history of literature, and ethnography. Here, one has to do with a more detailed term that describes Ukrainian "national science" — Ukrainian studies (ukrainoznavstvo), suggested by Mykhailo Hrushevskyi (Грушевський, 1904).

Almost a third of the audience were women, including members of the Circle of Ukrainian Girls, who promoted Ukrainian-language science in Lviv (Rohde, 2020). According to one of the participants, Nastya Hrinchenko, the Circle took an active part in the preparation of interesting educational activities that took place in the afternoons and were intended for Ukrainians from the Russian Empire. Despite the fact that there is no detailed documentary evidence of this activity, it is clear from memoirs that the young participants were interested not only in science but also in good company. In addition to the transfer of knowledge, these courses aimed at establishing symbolical ties between the politically divided Ukrainian lands (Kotenko, 2018), the scholarly community building and the establishment of personal ties between students. In addition, young women who demonstratively attended these courses manifested their desire to obtain higher education (Rohde, 2018).

However, there is no reason to consider this event a successful step on the way to a Ukrainian university (Rohde, 2019). The event should rather be considered as an important moment, in which the mission of Ukrainian scholarship was negotiated and new Ukrainian networks across borders were build and intensified.

Lviv through the eyes of participants from Russian-run Dnieper Ukraine

Volodymyr and Dmytro Doroshenko left the brightest memories of the summer courses (Дорошенко, 1930; Дорошенко, 1949; Дорошенко, 2011). They were students of the universities of Moscow and St. Petersburg. They were joined by Maria Dvernytska, Mykhailo Derkach and Dmytro Rozov (Дорошенко, 1949, 51). Their memories allow to understand how these two students, who visited Lviv for the first time, saw the city. Ukrainians who attended these courses, as well as scientific and literary events held by the NTSh and other institutions, initially imagined Galicia in general and Lviv in particular as a kind of "Eldorado" (Kotenko 2018).

When they arrived in Lviv and saw Polish signs on the city streets, their impressions changed: "We were not impressed by the appearance of the capital of Galician Ukraine either. Narrow, winding streets, which we passed on the way from the Pidzamche, those meager Jewish shops with their Polish inscriptions, seemed to us so provincial in comparison with Kyiv, with its wide streets, lush boulevards, majestic churches with their golden domes, with the dense greenery of city parks" (Дорошенко, 1949, 53). Nastya Hrinchenko, who came to Lviv from Kyiv in 1903 to study at the university, had similar impressions (Клименко, 2012).

Inviting Ukrainians from the Russian Empire, the organizers of the summer courses promised to provide them with accommodation for the duration of the courses. However, they did not fulfill the promise. Therefore, the Ukrainians appealed to the Academic Community, a Ukrainian student organization, to assist them in finding housing. Levko Hankevych helped them to find an apartment on ul. Kurkowa, which they liked because it was spacious and could accommodate everyone. Having settled, they all went to a canteen run by the Bratnia Pomoc, a Polish student mutual aid organization, since there was no Ukrainian student canteen, as Dmytro Doroshenko noted. Later, difficulties with finding an apartment arose again: "…we learned that the agitated landlord from ul. Kurkowa came running and said he could not accept us because the owner of the house, a Polish woman, said she would throw him out if he accommodated those Ukrainian haidamaks... What had we to do? We did not invent anything and decided to go to the Monopol [café] to meet Franko and to let it be as God wills" (Дорошенко, 1949, 53).

Before that, they learned that Franko came to the Monopol Café (opposite the monument to Adam Mickiewicz), the favorite meeting place of the NTSh board, every day at 5 p.m. (Дорошенко, 2011, 557).

Ivan Franko invited students to stay at his home for the duration of the courses. However, to the writer's shame, his wife was not enthusiastic about this idea: "Mrs. Franko was dissatisfied with the fact that a young, apparently emancipated woman from Ukraine was to live with her" (Дорошенко 1949, 55). In his memoirs, Dmytro Doroshenko wrote later that he had been shocked by the conservatism of Galician women and the conservative attitude towards women in Galicia in general.

Anyway, Franko was a very interesting person for the students of the vacation courses. They admired not only his clear manner of lecturing but also the simplicity and naturalness they did not expect from a great writer (Дорошенко, 2011). Levko Chykalenko, the son of Yevhen Chykalenko (who financed these courses), also visited Franko's house. After completing the courses, he went with Franko, who was visiting his brother, to Nahuyevychi. In 1947, already in exile, Levko Chykalenko fondly mentioned fishing together with Franko, an avid fisherman (Чикаленко, 2011).

A group of Ukrainian students, along with Dmytro and Volodymyr Doroshenko, eventually found housing at ul. Kurkowa 10. The girl who accompanied them settled in the St. Olha Women's Dormitory (founded in this building with the support of the Ruthenian Pedagogical Society — ed.), as well as Nastya Hrinchenko, who also felt a chilly attitude from Olha Franko (Загірня (Грінченко), 2011). Many Ukrainian emigrants from the Russian Empire lived at ul. Kurkowa 10, so this house was called their "colony" (Клименко, 2012, 150; Качмар, 2006, 116). Here the guests had the opportunity to communicate with socialist-minded emigrants and Galicians, who shared their views (among the latter were Levko Hankevych and Yulian Bachynskyi). Political debates for 20-25 people, including Dmytro and Volodymyr Doroshenko, took place in this apartment (Дорошенко, 1949, 59).

Doroshenko visited the NTSh building and the Society's library. First of all, Dmytro was pleasantly surprised by the liberal conditions of using the library. At the request of Volodymyr Hnatyuk, he became a regular member of the NTSh, in order to support Mykhailo Hrushevskyi at the general meeting of the Society on June 29, 1904 (Дорошенко, 1949, 58).

Fedir Vovk together with those attending his lectures visited the museums of the city, in particular the NTSh museum and the Dzieduszycki museum. In addition, he organized city tours, which were accompanied by intellectual conversations and anecdotes from his young years (Грушевський, 1904).

While the stay of the guests from Ukraine in Lviv and their contacts with the city residents are recorded only in a small number of documents, in memoirs one can see a broad picture of their familiarity with local features. Galician conservatism was most striking for the more progressive and often socialist-minded, ambitious young people from Ukraine. Their reactions to the lectures were also very different, as not of all the lecturers were experienced speakers and could convincingly convey their opinions to the audience (Rohde, 2020). For many attendees of the courses, including Volodymyr Doroshenko, who from 1909 until his death had close contacts with the NTSh, these courses were an opportunity to establish important contacts that later affected their lives.

Organizations

Related buildings and spaces

Sources

- Володимир Гнатюк, "Наукові вакацийні курси", ЛНВ, 1904, т. XXVII, кн. VII, 52-56;

- Михайло Грушевський, "Українсько руські наукові курси", ЛНВ, 1904, т. XXVII, кн. VIII, 102-113;

- Володимир Дорошенко, "Іван Франко (Зі споминів автора)", Спогади про Івана Франка / упорядник Михайло Гнатюк (Каменяр, 2011), 553-564;

- Дмитро Дорошенко, "Перші українські наукові курси у Львові в 1904 році", Діло, 1930, ч. 9, 2-3;

- Дмитро Дорошенко, Мої спогади про давнє-минуле (1901-1914) (Вінніпег, 1949);

- Марія Загірна (Грінченко), "Спогади про Івана Франка та його сеймове огнище", Спогади про Івана Франка / упорядник Михайло Гнатюк (Каменяр, 2011), 602-618;

- Людмила Качмар, "Іван Франко та наддніпрянські політичні емігранти", Вісник ЛНУ, Серія мист-во 2006, вип. 6, 114-120;

- Нінель Клименко, "Львівський період життя Насті Грінченко: сторінки біографії", Краєзнавство, 2012, 4, 144-154;

- Мартін Роде, "Внутрішньоімперські навчальні процеси? Національне питання Іннсбруцького університету на початку ХХ століття: галицько-український погляд", Сучасність минулого в урбаністичному просторі Чернівці-Іннсбрук / Курт Шарр, Ґунда Барт-Скалмані, укр. видання Світлана Герегова, Лариса Олексишина (Чернівці, 2019), 185-206.

- Левко Чикаленко, "Як ми з І. Франком ловили рибу", Спогади про Івана Франка / упорядник Михайло Гнатюк (Каменяр, 2011), 576-579;

- Anton Kotenko, "Galicia as Part of Ukraine: Lviv 1904 Summer School as an Attempt to Tie the Ukrainian Nation Together", Magdalena Baran-Szołtys et al. (eds.) Galizien in Bewegung: Wahrnehmungen – Begegnungen – Verflechtungen (Vienna, 2018), 257-275.

- Martin Rohde, "Innerimperiale Lernprozesse? Die Nationalitätenproblematik der Innsbrucker Universität im frühen 20. Jahrhundert aus galizisch-ukrainischer Perspektive", Scharr, Kurt/Barth-Scalmani, Gunda (Hrsg.), Die Gegenwart des Vergangenen im urbanen Raum Czernowitz-Innsbruck, (Innsbruck, 2019), 183–204.

- Martin Rohde, "Ukrainian Popular Science in Habsburg Lemberg, 1892–1914", Talk at the Urban Seminar (Center for Urban History of East Central Europe, 2018).

- Martin Rohde, "Ukrainian Popular Science in Habsburg Galicia, 1900-14", in: East/West: Journal of Ukrainian Studies 7, 2020, no. 2, 139–171.