An integral part of the Lviv ghetto history is the Janowska forced labour camp (Zwangsarbeitslager Lemberg-Janowska), which was the largest concentration camp for civilians in the territory of modern-day Ukraine. Scholars are now debating how to properly designate this camp because of the hybridity of its functions: not only that of forced labour, but also a transit and death camp.

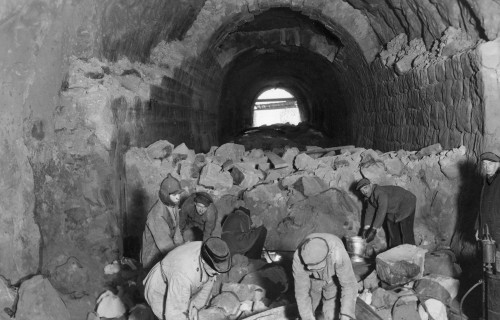

The camp was established in October 1941 by order of the Governor of the District of Galicia, Dr. Otto Wechter, and the SS Police Major General Fritz Katzman. Territorially, it was located on former ul. Janowska (now vul. Shevchenka), which the Germans renamed Weststraße, from the building number 132 and further down the street to the modern penal colony number 30 (building number 156) near the Klepariv railway station. Before the war, there was a factory manufacturing flour mills there, owned by Steinhaus. A little up the street, at number 146, the ceramic factory of Lewiński and brickyards were located. During the first Soviet period (1939-1941), the Steinhaus factory was nationalized and placed under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Transport. When the Nazis entered Lviv, they set up two factories of their own, belonging to the United Industrial Enterprises and the German Armories. The camp was subordinated to the SS military-economic department (Deutsche Ausrüstungswerke, DAW).

Initially, the factories were a beneficial place to work, and many Jews and Poles tried to get jobs there. Until the beginning of October, factory workers were free to move around the city from their working places to their homes, but in early October 1941, Jewish workers were told that they were no longer allowed to leave their working places. The areas of the factories were fenced with barbed wire.

On November 1, 1941, a sign was established at the camp gate reading in German: "Der S.S. und Polizeiführer im Distrikt Galizien. Zwangsarbeitslager im Lemberg” (The SS and police of the District of Galicia post. Forced labour camp Lemberg). Initially, there were 350 Jewish craftsmen there producing equipment and ammunition. An eyewitness to the events associated with the camp formation, Janina Gescheles, recalls as follows:

Cesia Kolin's father worked on the construction of barracks on ul. Janowska. One day he was not let out and was locked up there along with the others. They slept in the barracks they were building. They were ordered to remove their armbands and to put yellow patches on the back and front. Cesia kept crying. She used to bring parcels for her father every day and stopped attending classes [in an underground school — ed.]. One day in front of the gate leading to the barracks an inscription reading "Zwangsarbeitslager" was hung. Now men began to be caught to be sent to the camp. It was very bad in the camp. The “campers” were beaten ruthlessly and looked like the living dead, walking skeletons.

In December 1941, there were already 554 Jews in the camp. In March 1942, about 400 workers were brought there from Lviv. Over the following two months, another 4,000 from other towns near Lviv were also brought there. In August-November 1942, new Jewish workers were brought to Lviv while the exhausted prisoners were sent to death camps.

The camp consisted of three parts: 1) administrative buildings, SS premises, a "selection" camp, 2) prison barracks, and 3) DAW factories. It had a male part and, later, a female part. Prisoners were engaged in forced labour both inside and outside the camp. Constant bullying, illnesses, and violent actions led to the camp constantly needing new influx. Witnesses and participants in these events — Philip Friedman, David Kahane, and Felix Horn — describe their stay in the Janowska camp in their memoirs.

Prisoners of the Janowska camp were killed in various ways. In addition to the invariably hard and exhausting 10-12 hours of work, the daily beatings and bullying exhausted the prisoners finally. Willhaus came up with the so-called BCD vitamins (B for belka, “beam”; C for cegła, “brick”; D for deska, “board”) for “campers”. After a hard day's work, the “campers” were ordered "in addition" to load heavy bricks, beams or boards on themselves and to run with them (im Laufschritt) back and forth (mostly from the Klepariv station to the camp or back).

(Philip Friedman)

I was lying on the sixth, upper tier of the sleeping bunks. [...] From now on I don't have a name, I am just number 2250.

At 4.30 in the morning the lights were turned on and the voice of the man on duty was heard in the barracks: "Get up, Jews, get up, campers, get up, dickheads, go to work!"

Immediately the barracks were on the move. The race for the toilet and washbasins began. In both places, long queues quickly formed. To make the lives of the prisoners as miserable as possible, the toilet and washbasins were deliberately made clearly too small and far apart. Those who managed to quickly cope with these two morning procedures, hurried to take their place in the longest queue — the queue for the kitchen. For the unbearable workload the exhausted prisoners had to endure, the breakfast was far too meager: black coffee and a slice of bread smeared with something resembling jam. According to the camp rules, all morning activities took 75 minutes. I must admit that I managed to cope with all the three of them just a few times. Very often the kitchen window was closed before I had time to get to it to be given my scanty breakfast.

At 5.45 all the prisoners were already lined up in the yard for the roll call. Everyone was expecting this morning ceremony with a feeling of horror. There always were people lucky enough to have escaped. And this always was a reason for punishment. For each fugitive, the SS man on duty could shoot three, four, or five Jews.

(David Kahane)

From that time on, I was taken to a labour camp on vul. Yanivska in Lviv. It was not a concentration camp, it was a labour camp, but they treated us just like in a concentration camp. We had to lie on wooden boxes, not in beds, there was nothing to eat, and we had to be on the Appell [roll call] at 5 a.m., in wintertime. We couldn't stand straight, and they beat us, they kicked wherever they could — on the stomach, on the back, on the sides. You couldn't fall 'cause they would shoot you. So there was an awareness of not to fall, all the bleeding always kept me aware of the need to stand up, and I was getting numb, for after a while I didn't even feel the beating. And then, around 7 a.m. or so, we were marching to the city to work. After a few days I thought: Well, there's nothing to hope for. So I ran away. And where could you go? I escaped to the dormitory.

(Felix Horn)

A path led from the barracks to the Pisky area, where ghetto residents and camp prisoners were killed during various periods of the occupation. Executions in this place began to peak after December 1942, when the Bełżec death camp was closed. Until then, it was there that Lviv residents and Jews from around the region were executed. There were no gas chambers in the Janowska camp at all; everyone was killed by shootings.

Before the arrival of Soviet troops, the Nazis, realizing that the bodies of those killed in the Pisky area would be used as evidence against them, decided to destroy the bodies. To do this, the Sonderkommando 1005 was formed of the camp prisoners to exhume the remains of the bodies and to burn them. The bones remaining from the burned bodies were also destroyed. In the Janowska camp, this process was well established, so workers from other camps were sent there for 10-day courses on how to dig up bodies and destroy remains. In addition to the bodies, some camp buildings, which could be used as evidence of Nazi crimes, were destroyed. These actions to destroy bodies and buildings and the lack of documents made it impossible to accurately ascertain the number of the dead, so the Soviet Extraordinary Commission used the mathematical method of calculation in the first place.

The camp existed until July 1944, when the camp's management took about 100 last prisoners and went with them first to Przemyśl and then to Austria, fleeing from Soviet troops.

In 1952, a penal colony was established in part of the Janowska camp territory, which still exists today. Until the 2000s, a dog farm was located in the Pisky area. Due to all this, it was impossible to conduct research involving modern equipment. Only in the 2000s it was allowed to establish a commemorative sign there — a stone with an inscription telling about the death of the Jews. After the dog farm was removed, the territory was designated as a "park" and partially became a place of rest for Lviv residents.

All this slowed down the study of the real picture of events. In recent years, the number of victims has been debated. According to contemporary research by Ukrainian historians Oleksandr Kruhlov, Andriy Umansky, and Ihor Shchupak, the number of deaths in the Janowska camp in 1941-1943 ranged from 13,000 to 15,000. Taking into account these and other studies, such as that of Waitman Beorn, we can assume that the number of deaths in the Janowska camp in the entire period of its existence ranges from 30 thousand to 80 thousand people. This figure is much lower than that published immediately after the war by the Extraordinary State Commission — 200 thousand. The previous figure was prepared before the Nuremberg Trials and could indicate the need to confirm and give more weight to Nazi crimes in court, as well as to divert attention from Soviet war crimes in the same area. In addition, Jews were often included in the total number of victims, which also led to an increase in numbers.

During the commemoration of the victims of the Nazi occupation in the late 20th - early 21th century the data of the Extraordinary State Commission was used in inscriptions on the monuments. Today's discussion of the transition to modern research and the reduction of the death toll has led to opposition on the part of some members of Lviv's Jewish community, who flatly refuse to accept another version, although reducing the numbers does not mean reducing the gravity of the crime against the Jewish community.

The study of the Janowska Hybrid Camp should reveal its role in the global Nazi project of genocide, as there were all forms of extermination of Jews, collaboration, seizure of property, mass killings of Soviet soldiers and prisoners of war, Jewish resistance, deportations in this camp. The important question is whether this phenomenon was typical or unique.

Work is underway to organize the areas of the shootings, and a memorial complex will soon be erected there, telling about the past events.