The theme was prepared as a part of the program The Complicated Pages of Common History: Telling About World War II in Lviv.

The citizens of Lviv saw the beginning of a military conflict between the Third Reich and the USSR with different expectations. Some were convinced that with the Germans it would be possible to establish a better life and bring order, while others were more pessimistic. Some part of the Ukrainian population expected a real opportunity to gain independence and restore statehood after a failed attempt in 1918-1919. Jews were mostly afraid of the unknown future.

From the first days of the Nazi occupation of Lviv, it became clear that the Nazis had their own plans for these territories and populations. In Lviv, the implementation of the Third Reich’s state program of the extermination of Jews and Roma in the General Government, i.e. in the regions of Warsaw, Lublin, Radom, Krakow and Lviv, began. Subsequently, the extermination became large-scale and planned, and from early 1942, after the conference in Wannsee (according to other sources, from late 1941), it was code-named Operation Reinhard. In general, the operation was part of a broader concept of the extermination of Jews during World War II, to which the term Holocaust will be applied. This section will also use the term Holocaust to refer to the extermination of Jews during World War II.

We will look at the structure of the Holocaust in Lviv, focusing on the time frame and topography of the genocide, the anti-Jewish policies of the Nazis, the survival strategies of Jews and non-Jewish victims of Nazism.

The reaction of the non-Jewish population of Lviv is described in detail in two other sections dedicated to the events of World War II — "Collaboration" with the Nazi regime and "Reactions of Lviv residents to the Holocaust". It will be mentioned in this section to outline the subject matter and to remind that not only the Nazis and Jews took part in these events.

The Nazi occupation of the city lasted from June 30, 1941, till July 27, 1944. During this time, the city underwent radical changes. First of all, they concerned the urban space as the ghetto, a separate area for the forced isolation of the Jewish population, was allocated, the Yanivsky camp and other places of forced labor were created, as well as a camp for Soviet prisoners of war; also, a system of deportation of Jews from Galicia through Lviv to death camps was established, and controlling and executive bodies (both those of the occupiers and Jewish) were organized, which worked under the constant supervision of the Nazis. At the same time, after the front moved to the East, theaters, cinemas, schools, hospitals, mass media, shops, public transport, etc. resumed their work in the city.

During the war, the ethnic composition of Lviv also changed. Before World War II, more than 50% of Poles, 32% of Jews and about 16% of Ukrainians lived here. After the liberation of Lviv by Soviet troops in 1944, up to 2,000 of the city's 32% of Jews survived. According to the Extraordinary State Commission for the establishment and investigation of the atrocities of the Nazi invaders and their allies and the damage they caused to the communities, collective farms, public organizations, and state-owned enterprises of the USSR, 130,000 to 150,000 Lviv Jews were killed.

The Nazis' strategy was first to turn the non-Jewish population against the Jewish community, to intimidate the community itself, and then to form a structure to control, exploit and exterminate the Jews.

The intimidation began with the Nazi-planned pogrom in Lviv, largely carried out by the local non-Jewish population. Violent actions against the Jews lasted almost all of July, with the largest events taking place at the beginning and end of the month.

The structure set up for the plunder and exploitation of Jews included the Judenrat (a Jewish council under Nazi control), the ghetto (a compact place of Jewish residence), places of forced labour, and the Yanivsky camp. Although the Judenrat was a Jewish council, it was completely subordinate to the occupying power and governed the daily life of the Jews in accordance with the orders of the Nazi authorities. The ghetto was to ensure quality control over the Jewish population as the entire Jewish community had to find itself in one closed area of the city. The Yanivsky camp had hybrid functions: imprisonment, forced labour, transfer to other camps and places of murder. This camp became the epicenter of the persecution and extermination of Jews not only in Lviv but in the region as a whole.

One can read about the survival strategies of the Jewish community, its reaction and actions during the Holocaust in Lviv in the memoirs of witnesses (Jews and non-Jews), studies, the press, chronicles, diaries, archives, etc. From the first days of the occupation, the city's Jewish community was in a state of fear of the unpredictable future. Part of the Jewish community was convinced that if they followed all the instructions of the Nazis, it would be the right way to save at least their own lives and the lives of their loved ones. In Lviv, the Nazis organized the Judenrat. One of its subdivisions was the Jewish Order Service. The existence of these bodies usually raises many questions for modern researchers: whether their workers can be considered collaborators, whether those who worked there had a choice to agree to this work and follow the instructions of the occupiers, whether the workers could disobey the Nazis and save the community. In addition to the Judenrat and the Jewish Order Service, Jews worked in factories set up by the Nazis and in non-Jewish private businesses (with the consent of the Nazis and with all necessary paperwork performed) or were engaged in forced labour in the ghetto or in the camps.

Some members of the Jewish community were involved in the resistance movement withstanding the occupying power. However, much less is known about the Lviv Jewish underground than, for example, about the Warsaw underground. There were some isolated cases of armed resistance to the Nazis.

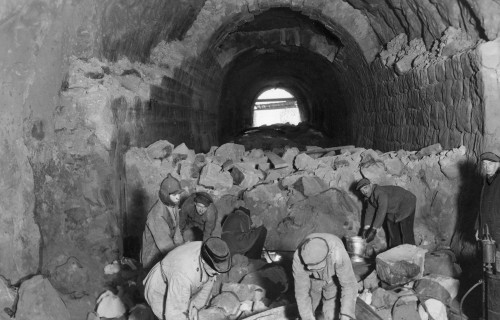

Some tried to escape to the "Aryan" part of the city with forged documents, some hid in the city sewers, in basements, attics, apartments of pre-war acquaintances or friends, in monasteries and churches, some Lviv Jews escaped outside the city, where they were more likely not to be recognized and reported to the security police and the SD (Sicherheitsdienst, ger. for Security Service). However, constant raids by the Nazis and the Ukrainian Auxiliary Police, denunciations by neighbours and casual witnesses, did not allow a large number of Jews to escape.

The Holocaust in Lviv ended in July 1944 with the arrival of Soviet troops. However, this did not put an end to individual violence against Jews; besides, it was also the beginning of a long silence and distortion of information about the wartime events. This was due to the post-war Soviet narrative, which included the creation of an image of the victorious Soviet people and the concealment of Soviet war crimes in the territories occupied under the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact. While during the war and in the first postwar years the Soviet media sometimes mentioned the special fate of the Jews, the following forty years of the victorious narrative and the communist regime in Ukraine put an end to the Holocaust debate.

According to the victorious Soviet narrative, formed in the 1960s, there was a single Soviet nation that suffered at the hands of the "fascists" (the word "Nazis" also did not fit into the new narrative). Despite all the losses, it was the Soviet people that won the war. A story telling that one of the peoples of the USSR suffered greatly and was a great victim did not correspond to the general concept. The facts of collaboration of some part of the Soviet population with the Nazis did not fit into this concept either. In addition, there were virtually no Jews left, as was, in fact, most of the prewar population, in the places where they once lived. They were replaced by their former neighbours and new residents, who often deliberately seized abandoned property, in particular apartments (before the status of this property was "normalized" by the Soviet authorities).

There were virtually no public attempts to discuss the suffering of the Jewish community, indicating all the places of death, as this could be interpreted as a manifestation of Zionism and lead to catastrophic consequences. Especially against the background of deteriorating relations between Israel and the USSR and the policy of official anti-Semitism (closure of the "Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee" in 1948 due to "anti-Soviet propaganda", the Doctors' plot, ban on Jewish religious communities, etc.).

Representatives of various nationalities who came to Lviv, in particular, ethnic Ukrainians, were given the opportunity to occupy all the niches that had previously been filled by Jews and Poles. For the new residents of the city, the issue of the Holocaust and post-war violence was irrelevant. Moreover, they used the situation for their own social advancement. In addition, in the postwar period many officials shared the anti-Jewish prejudices nurtured in previous years due to the policy of forming homogeneous territories. Meanwhile, the Holocaust dissolved into the general memory of the war.

After the war, the Soviet Union was also interested in overestimating the number of victims of Nazism. This was especially necessary to increase the influence on the general consciousness during the trials of the Nazis. Subsequently, the discussion of these figures in the Soviet Union was stopped altogether. This led to the fact that, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, some inflated figures were without analysis made part of many studies (or memoirs).

Other victims of Nazism in Lviv included prisoners of war (first Soviet, and later Belgian, Italian, French) and Roma. While the place, where the POW were concentrated, is known — the Stalag 328 camp, located in the territory of the former Citadel (its Eastern bastion tower on the Kalicha hill, which during the existence of the camp was used as a death tower, has recently been transformed into a hotel named the Citadel Inn), as well as the number of prisoners and the dead, there is no clear data on the Roma due to lack of memories and research.

The suppression of the Holocaust events in the Soviet Union and the formation of different cultures of memory on both sides of the "Iron Curtain" led to the fact that the Holocaust is a topic around which there is much controversy and debate. The two extreme points of view are either the denial of the Holocaust or the fact that only Jews can speak about the Holocaust and the Jews in it.

Researchers are examining various issues in the Jewish community's relationship with the Nazis and the non-Jewish population. One of the most controversial issues is still the role of Lviv's non-Jews in the Holocaust: whether it would be possible to exterminate almost 32% of the city's population without the help of Ukrainians and Poles, whether interethnic relations in pre-war Lviv were really friendly, and how the Holocaust could take place in the conditions of interethnic understanding and support, whether to consider work in the Judenrat or the Jewish Order Service as a manifestation of collaborationism, how to count the victims of the Holocaust, despite all the measures taken by the Nazis and the Soviet authorities to falsify or conceal real figures.

List of places:

- Political killings as a tool of propaganda

- Entertainment industry as a means of propaganda

- "City scum", nationalists or ordinary people: interethnic violence on the streets of Lviv

- Choice without choice?

- District IV of the City: At Home But Without A Home

- Hybrid camp: Janowska camp

- The role of transport in the Holocaust

- Murder of the City

- Collaboration or survival: Jewish Order Service

- Prisoners of war in Lviv

- Places of forced labour