Raj Cinema ID: 264

Сinema as the tool of propaganda. Repertoire of Lviv cinemas. Impressions of Oleksandr Dovzhenko from his work in Lviv. The chronicle film "Liberation". This story is a part of the theme about Soviet Occupation in 1939-1941, prepared as a part of the program The Complicated Pages of Common History: Telling About World War II in Lviv.

Story

One of the many cinemas, where Soviet-made feature and documentary films were shown in 1939–1941, was located in the building on pl. Mitskevycha 6/7. In 1930-1943 it was called Raj (Paradise); after the war it was renamed after Lesya Ukrainka. It ceased to exist in 2007.

For the Soviet government, cinema was one of the main tools of propaganda; for the people of Lviv, it was one of the few allowed and affordable kinds of recreation. Therefore, with the beginning of the Soviet occupation in Lviv, the number of cinemas gradually increased: from seven in October 1939 to 25 in the early December of the same year.

On the first day of the occupation, September 22, 1939, the first screening of the Soviet film "Lenin in 1918" took place. From November 1939, more and more Soviet films appeared in Lviv cinemas, such as "Maxim's Youth", "Chapayev", "The Rich Bride", "Mitka Lelyuk" and others.

Even after the war erupted, it was possible to watch foreign films on some screens in Lviv; over time, however, the association of cinema owners, adapting to the new situation, decided to show only Soviet films. Subsequently, all Lviv cinemas were nationalized.

As the occupation of Lviv took place under the slogan of "liberation" of Ukrainians, the Soviet authorities prepared a corresponding repertoire for the Ukrainian audience — films like "Taras Bulba", "Bohdan Khmelnytsky", "Minin and Pozharsky", "Suvorov" and others. These works had a clear anti-Polish accent, were in Ukrainian or Russian, and aimed to prove the justice of the "liberation" of Western Ukraine from the "Polish yoke." In November 1939, the first colour film was released — "The Sorochyntsi Fair"; the film was broadcast in Ukrainian, but with Polish subtitles.

In total, about 120 Soviet films were brought to Lviv in early December 1939. Lack of other available entertainment, relatively low ticket prices, a large number of shows during the day contributed to an increase in the number of spectators in the first year of Soviet occupation. Over time, however, interest in overtly propaganda films produced in the USSR began to decline, as most of them were of low artistic quality and were made by the same pattern. It was only the export of films from abroad that allowed the Soviet authorities to bring viewers back to cinemas. The first foreign film shown in Soviet Lviv in 1940 was “The Great Waltz”, whose popularity could not be surpassed by all Soviet films combined. In 1941, Charlie Chaplin's last silent film, “New Times”, appeared on the screens. During the Soviet occupation of Lviv, along with feature films, full-length documentary chronicles typical of the USSR began to be shown and produced, such as "Comrade Stalin's Report on the Draft Constitution during the VIII Extraordinary Congress of Soviets", and so on.

The best Soviet artists were trusted to shoot documentary chronicles in the occupied territories. One of the best was Oleksandr Dovzhenko, a Ukrainian Soviet film director whose works rightly belong to the world cinema heritage. Anyway, absolutely all of Dovzhenko's films can be called propaganda as all Soviet art was to reflect the party's policy and promote communism. Dovzhenko adapted his directing talent to regular party slogans and concepts that promoted the ideas of industrialization and collectivization, the eternal struggle against everything and everyone, the conquest of nature, the participation in the civil war, and the "liberation" of territories with accents that satisfied Soviet censorship. It was to fulfill another state commission that the director arrived in Lviv with his wife, Yulia Solntseva. She mentions their work in the city as follows:

We lived in Lviv for a few days and started filming everything interesting and unexpected that we encountered. The cameraman Y. Yekelchyk, who worked with us, could not get used to shooting documentary materials and therefore felt bad. He could never do anything in time. Anyway, he was a great cinematographer. What had we to do? [...] We shot a lot of material in Lviv and also stayed in other places that were interesting to us.

Lviv made an unforgettable impression on the couple, interesting in that it is the opinion of people who worked in the USSR, first came to the "liberated" city, were happy to communicate with locals and, as artists, could not help but notice how different newly arrived citizens looked and could not help seeing the reaction of the local "bourgeois" and bohemian public, which, despite Soviet realities, still looked different. From the memoirs of Yulia Solntseva:

We entered the restaurant because there was no other place to have dinner. We were impressed by the incredibly richly dressed visitors and the load music. All tables were occupied. We — me, Dovzhenko, Shklovsky and two more of our comrades, also dressed in military, — stopped at the door of the hotel. All eyes turned to us. Our clothes did not fit the general appearance of the restaurant in any way. So the whole restaurant turned in our direction. The music suddenly stopped. We felt we were in a difficult situation but we were really hungry, so we walked between the tables, where people were sitting and looking at us with depressing eyes.

Finding a free table, we sat down. A waiter came up to us. Shklovsky turned to Oleksandr Petrovych: "Sashko, we obviously got to a wrong place, we need to get out immediately." Taking the menu, we began to look it through, pretending that there was nothing suitable for us, and then we got up and left. The other visitors were sitting in absolute silence. Everyone was watching our movements, and this made it even harder for us.

These private impressions did not hinder the creative work, and the result of Oleksandr Dovzhenko’s and Yulia Solntseva’s stay in Galicia was a Ukrainian documentary historical chronicle film "Liberation". It was released on July 25, 1940, in Ukrainian and Russian. Dovzhenko wrote the off-screen commentary for it and was its editor.

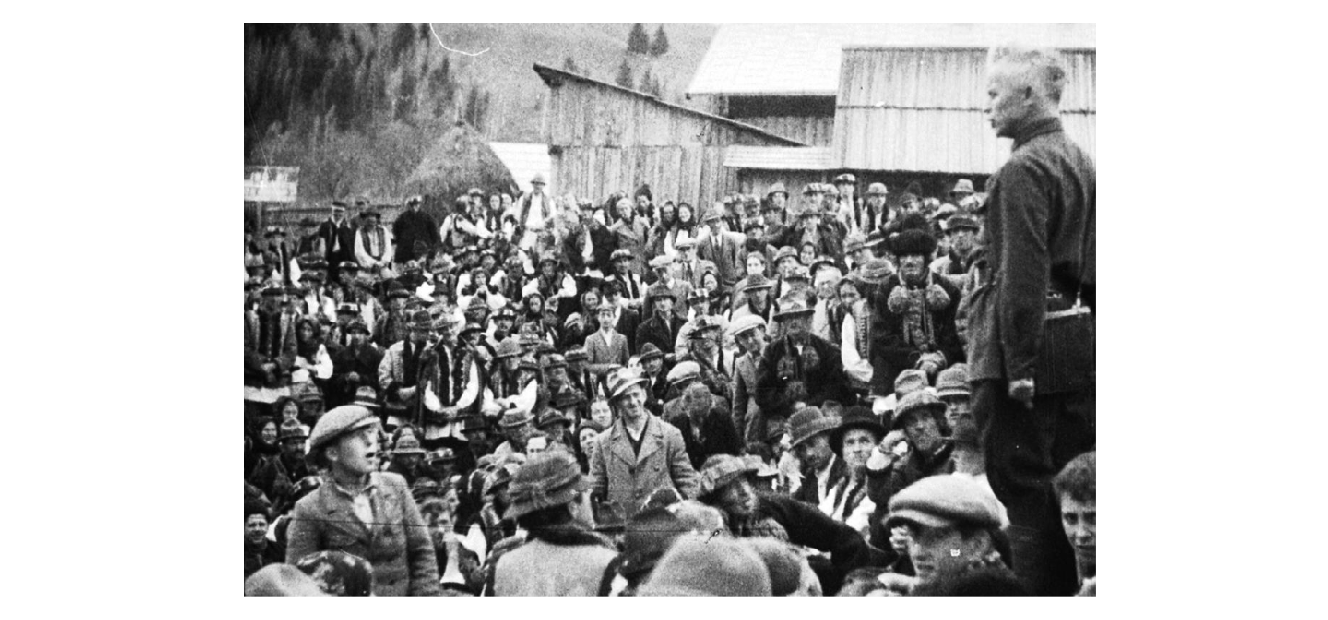

The chronicle film "Liberation" tells about the arrival of Soviet rule in the territory that was part of Poland before the war. The main idea was to show the joy and happiness of peasants, workers and residents of Lviv caused by the regime change. The shots depicting the welcome of the Red Army by the Hutsuls and the Pochaiv Lavra monks’ unanimous vote for the establishment of Soviet rule were to prove the unanimous position of all the inhabitants of Western Ukraine in their consent to become part of the USSR.

The Lviv episode in the "Liberation" is not very long. The first shots show the architecture and streets of the city, the monument to Jan Sobieski, who, the voice-over warns, must not be confused with Bohdan Khmelnytsky; however, from the first minutes of the text it is clear that in the future the main accents in the city history will be what monuments will be left and what terminology will enter the daily vocabulary of the new Soviet citizens. One of the arguments in favour of the "accession" of Western Ukraine is the common history and common origins of the three Slavic peoples: Ukrainian, Russian and Belarusian. Also, the eternal desire of the "brothers" to be together in one state is emphasized, as well as the peasantry’s common struggle against "Roman Catholicism" and the "Polish gentry" and the difficult economic situation of the local proletariat. Among the main historical figures associated with the city, the film focuses on "people's fighters" against the "Polish gentry" — Ivan Pidkova, Bohdan Khmelnytsky and Maksym Kryvonos; however, the twentieth century is not forgotten as Oleksandr Parkhomenko is mentioned, one of the leaders of the military garrison of the First Cavalry Army of Semyon Budyonny, and the "steel divisions" of Semyon Tymoshenko, who, according to the authors of the film, was greeted in Lviv with bread and salt. They did not forget to mention Ivan Franko, who is called a democratic writer, as well as Adam Mickiewicz, whose monument in Lviv became a place for rallies and demonstrations.

While from an ideological point of view Dovzhenko's film "Liberation" is a typical example of Soviet agitation, from an artistic and aesthetic position the film is a very interesting example of cinematography. Dovzhenko's team included four cinematographers, and newsreels made by other artists were also used. Despite the off-screen text of typical Soviet propaganda, it is the footage of conversations and meetings of Lviv residents with Red Army soldiers that is very much alive and real and is still widely circulated as an example of a documentary chronicle of Lviv in 1939–1941.

Almost forty minutes of the one-hour-long film are dedicated to speeches of citizens, newly elected delegates and representatives of the top party leadership; this part of the film is the most predictable and least interesting.

On September 11, 1940, the documentary "Liberation" was shown in Lviv on the occasion of the "reunification" anniversary. However, the film did not last on the screens long and disappeared soon. Now the entire film and Lviv fragments of this chronicle are available for viewing at the Dovzhenko Film Studio in Kyiv, at the Center for Urban History in Lviv, as well as on the Internet. They are undoubtedly worth reviewing and discussing.

Sources

- Віра Агеєва, Сергій Тримбач, Довженко без гриму: листи, спогади, архівні знахідки (Київ: Комора, 2014), 472.

- Grzegorz Hryciuk, Polacy we Lwowie 1939–1944, Życie codzienne (Warszawa: Książka i Wiedza, 2000), 430.

- Documentary “Liberation”, directed by Oleksandr Dovzhenko, Yulia Solntseva. Освобождение, (accessed on 05.02.2019).

- Сергій Тримбач "Без жодних купюр!", Щоденна газета "День", Без жодних купюр (accessed on 05.02.2019).

Cover photo: Pre-election meeting in Hutsulia. Oleksandr Dovzhenko is delivering a speech. Courtesy of the Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance.