The Central National Council (Centralna Rada Narodowa) ID: 126

The Council was the main representative body of the Polish revolutionary movement in Lviv during the Spring of Nations in April-November 1848. It sought liberal constitutional reforms, the establishment of a Polish administration in Galicia, the Polonization of education, and the abolition of serfdom. It started a new "legalistic" stage in the Polish national movement in Galicia. This publication is a part of the Spring of Nations in Lviv project.

The Central National Council (pol. Centralna Rada Narodowa) was the main representative body of the Polish national movement throughout the Spring of Nations operating in Lviv from April to November 1848. It sought the implementation of liberal constitutional reforms, the establishment of a Polish administration (autonomy) in Galicia, the introduction of the Polish language in education, and the abolishment of serfdom. The Council consisted mostly of representatives of the petty gentry, intelligentsia, and aristocracy of liberal views.

The Council adhered to legal methods of struggle, formed a Polish faction in the Reichsrat and created the National Guard. Its main political opponents were the governor of Galicia, Franz Stadion, his loyal conservatives, the newly formed Ruthenian (Ukrainian) national movement, as well as Polish radicals in exile. The government abolished it after suppressing the uprising in Lviv on November 1, 1848, and imposing martial law in Galicia.

The Polish Issue on the Eve of the Revolution

The "Polish issue" was one of the main political problems in Eastern Europe throughout the nineteenth century. After the partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth between Russia, Prussia, and Austria, the restoration of a united state within the borders of 1772 became the main task of the Polish movement, with armed uprisings and conspiracies as its main tools.

For a long time, it was the Russian Empire that remained the main area of its activity, as most of the territories claimed by the Polish movement were located there. It was there that, after Napoleon's invasion supported by thousands of Polish volunteers, the autonomous Kingdom of Poland emerged. It was there that the first large-scale Polish uprising of 1830 took place. After its defeat, the autonomy was strictly curtailed, and thousands of insurgents — those who still had not found themselves in exile by that time — resorted to large-scale emigration, mostly to France but partly also to Austrian Galicia.

The so-called "Great Emigration" in Paris played a significant role, often a coordinating one for the Polish movement. It comprised two wings: the conservative and a more radical one. The former, led by Prince Adam Czartoryski, preferred using diplomatic methods for the revival of Poland. The latter, the Polish Democratic Society, coordinated conspiratorial structures and took part in preparing new uprisings on the Polish lands.

Meanwhile, Austrian Galicia remained just a "province" for the Polish cause. The Habsburg monarchy was ruled by Chancellor Metternich's "police" regime; and the administration in Galicia was carried out by governors appointed, in their turn, from Vienna. Besides, Lviv, with its German-speaking university, numerous Austrian bureaucracy, and imperial military garrison was hardly a city to play the role of a national center.

After the Napoleonic Wars there were only a few concessions to the Polish movement here. Among them was the functioning of the advisory body called Galician Estates, a Polish language department was opened at the University, as well as the Ossolineum, which became the main scientific institution in the province, and a few Polish-language journals became published. All Polish national life in Galicia concentrated around these institutions until the mid-nineteenth century.

The only attempt at an uprising in Galicia in 1846 ended in complete fiasco at its very beginning. Organized by radical emigrants and local conspirators (often refugees from the Russian Empire), the rebels were defeated not by the imperial army but by their "fellow" peasants, whose support they relied on in the first place. As a result, more than a thousand rebels were killed, many were forced to emigrate, and Krakow, a "free city" until then, was officially annexed by the empire and incorporated into Galicia.

This way, the eruption of the Spring of Nations caught the Polish movement in Galicia by surprise. Its leaders had just been recovering after the physical and moral defeat of two years before. This way in the mid-March 1848, when news of the revolution in Vienna and Chancellor Metternich's flight reached Lviv, they were not at all certain of popular support and were not ready for new armed protests against the government. The fiasco of 1846 defined the tactics of 1848: the Polish movement both deliberately and forcedly switched to moderate positions and legal methods of struggle.

Creation of the Council

The National Council was established in Lviv on April 14, 1848. It was conceived as a broader representative body of the Polish national movement in Galicia to replace the previous National Committee (Komitet Narodowy). The latter was the first open political organization, which had functioned in the province since March but had no branches throughout the land, and represented thus only Lviv circles.

The immediate impetus for the creation of the Council was the news that the governor of Galicia, Franz Stadion, after a month of revolutionary events in the empire, decided to revive the old Galician Estates, which had not been convened for the previous three years. This institution, which functioned in Lviv in the first half of the nineteenth century, consisted of representatives of the upper classes and the clergy and had a purely advisory function. Its members could compose petitions addressed to the emperor with their recommendations for governing the province. As it was said then, the Estates could only "ask the emperor for what he never gave and thank him for what he was never asked for." Revolutionaries deemed the Estates to be a poor substitute for a full-fledged provincial Sejm, which would represent all social classes and would have some real power in the province (apparently limited by supervision from Vienna); it was the latter that they sought. Even a large part of the aristocracy sitting in the Galician Estates wished for more power than they were endowed with.

Under such circumstances, the Lviv revolutionaries decided to create their own alternative representative body, which would give them the right to speak on behalf of the entire crown land. On April 14, more than 20 representatives (according to other sources, 17) of the National Committee gathered in Tomasz Kulczycki's house on the Ferdinandsplatz. There were both those who had returned from the delegation to Vienna, as well as those who did not take part in it. They formed thus a new organization called the National Council (pol. Rada Narodowa).

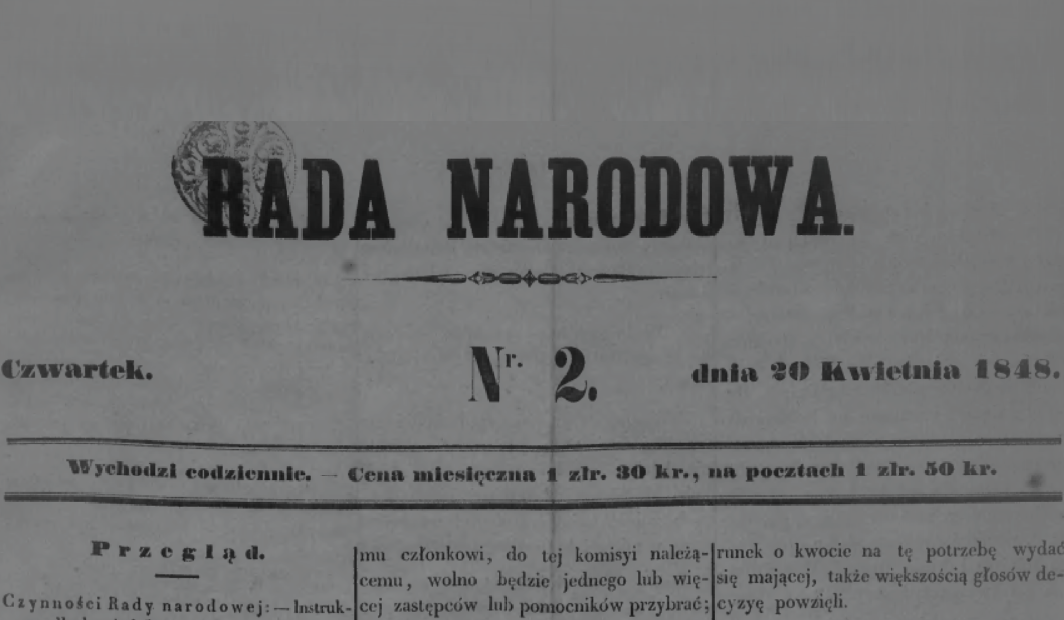

In the first week of its activity, the Council positioned itself as the editorial office of the newspaper of the same name. The first issue of the Rada Narodowa (later renamed Gazeta Narodowa) came out on April 19. Freedom of the press was proclaimed in Lviv in late March, therefore such form of activity could not cause any legal suppression. This way the Council declared itself and began to act as a leading political force, aiming to represent the people of the whole region before the authorities. As it stated in the first issue of the newspaper, the Council was to become "an organ not of a single party or an individual, but, in fact, a collective representative body of all national elements" (Rada Narodowa, 1848, No. 1).

Demands and Initiators

The National Council's program was based on the petition to the emperor, which had been drawn up on behalf of the Lviv public and signed by thousands of Lviv residents on March 19, the first day of the revolutionary events in the city.

The demands set out in the petition envisaged broad political and social reforms in the province. The petition demanded basic constitutional freedoms; equal political rights for all inhabitants of the monarchy; the introduction of Polish (local) administration in Galicia; the restoration of self-government; the creation of a provincial Sejm (or reorganization of the existing Estates); the introduction of the Polish language in education; the formation of a national guard in the province; and, finally, the abolition of serfdom and any feudal obligations. The petition also contained some minor demands, such as immediate release of all political prisoners. These postulates became the main political program of the Polish movement during the 1848 revolution.

The chief initiators and authors of the petition, who became the core of the Polish movement in the first month of the revolution and later the founders of the National Council, were two circles, united by the revolutionary moment and common views on the situation.

One of them consisted of "professional" Polish revolutionaries — Franciszek Smolka and Florian Ziemiałkowski. In previous years, they belonged to secret circles and participated in the preparation of the uprising. Some of them, like Smolka, were initially sentenced to death but were later pardoned by the emperor. It is to Smolka that some sources attribute the initiative to create the National Council.

The other circle was a group of writers united around the Dziennik Mód Paryskich newspaper. Founded and maintained by Tomasz Kulczycki, a wealthy tailor, the newspaper had earlier departed from its original "tailoring" theme and, despite its name, became the main literary periodical in Lviv. With the eruption of the revolution, the edition openly engaged in political activities. Its editor, Jan Dobrzański, and regular contributor, Józef Dzierzkowski, were among the leaders of the protest movement in Lviv, while the owner Kulczycki repeatedly placed his house at the Committee's or, later, Council's disposal for regular meetings. Dobrzański also became the editor of the main press organ of the Council, which emerged on the basis of the Dziennik.

Both of these circles belonged to the so-called secular intelligentsia. Descending mostly from petty gentry, they were deprived of their status under the Habsburgs, and therefore they engaged in free professions. Only some of them, such as Smolka, came from the families of Austrian officials or military acculturated in the Polish environment.

Their petition found support from almost all sections of society (except for extreme conservatives and government supporters). Gaining support of the upper strata of society was crucially important for the newly formed movement and their influence. On the first day, March 19, the aristocrats — those who shared the intelligentsia's reformist views (albeit in a somewhat more moderate form) — personally signed the petition drafted by the revolutionaries. By doing so they added significant political weight to it, both in the eyes of the public and the government. It was they who headed the delegations to the governor and later to the emperor in order to present the public's demands to the authorities.

The National Committee which formed around the petition, included representatives of various social classes. There were intellectuals, clergy, aristocracy — as well as different religious denominations, namely, Roman and Greek Catholics and Jews. Among the founders of the National Council on April 14 there were lawyer Franciszek Smolka and editor Jan Dobrzański, counts Aleksander Fredro and Tytus Dzieduszycki, Roman Catholic priest Roman Zubrzycki and Greek Catholic priest Onufriy Krynytskyi, lawyer Oswald Menkes and banker Abraham Mises, who were both Jews. Moreover, all members of the delegation to the emperor, who, on behalf of the Committee, had at that time gone to Vienna to submit the petition with public demands to the emperor, were immediately included in the Council in absentia.

However, most aristocrats, including those who supported the petition in March, stood aside from the Council's activities during the first weeks after its foundation. Even those who took part in its creation on April 14 did not take an active part in its activities. There could be two reasons for this. Firstly, the Council remained an organization not officially recognized by the government (hence semi-legal), which could be a problem for those who supported legal methods of activity, mostly aristocrats; secondly, the aristocrats were waiting for the convening of the Galician Estates, announced by the governor, in which they were to take part. Both obstacles were removed in late April.

An Alternative to the Galician Estates

The restored Galician Estates were to be opened on April 26 as scheduled by the governor. On April 21, the Council issued an appeal to its members urging them not to agree to resume its activities.

On April 25, on the eve of the Estate's opening, a solemn service was celebrated in the Latin Cathedral in honor of the Emperor Ferdinand's birthday. Unexpectedly, the Council representatives came to stand in the church by the governor, as if they were an equal source of power in the province. On the one hand, the Council's participation in the service was to demonstrate the loyalty of the Polish movement personally to the emperor and the monarchy, while, on the other hand, it symbolically challenged the authority of the governor in the province.

On the same day, after the liturgy, the governor, who had so far ignored the Council as a political force, invited Franciszek Smolka and suggested that they, including several members of the Council, "discuss public affairs" (Schnür-Pepłowski, 1895). Smolka refused, because it was at the same time that a preliminary meeting of delegates to the Estates was held with the participation of several invited members of the Council in the Ossolineum halls. After a short discussion, its participants decided by a majority vote to withdraw from the Estates and declare it invalid. This was regarded as the first significant victory of the Council, which itself arose as a counterweight to the Galician Estates and used all its influence to prevent its restoration.

At 4 a.m. on the following day, in response to the failure of the Estates, the police broke into the hall of the National Council, confiscated its documents and sealed the premises on the governor's instructions, outlawing the Council. In response to the sudden crackdown, the Galician Estates members delegated 20 of their representatives to the Council, which continued to meet in private quarters, not only expressing their support for it in this way but also effectively taking it under their "care" before the government. Among those Estates members who joined the Council there were influential aristocrats such as Leon Sapieha, Leszek Dunin-Borkowski and others, and also one of the two Catholic hierarchs in Galicia (the Lviv archbishopric was vacant at that time), Franciszek Wierzchlejski, the then Bishop of Przemyśl and the future Archbishop of Lviv.

Having received such solid support, the Council rather soon persuaded the governor to unblock its premises in the "old theater" and to actually recognize and accept its existence. In the following days, the Council continued to accept representatives from the province, and on May 1, it accepted several peasants from different counties as symbolic representatives of their estate. The number of its members grew up to 80 people.

Meanwhile, in about the last days of April the Lvivians read the text of the constitution, which was promulgated on April 25 in Vienna by the emperor (Gazeta Lwowska published it only on May 3, but mentions of the new constitution appeared in the press a day or two earlier; at that time, it took several days for information from Vienna to reach Lviv). The constitution did not grant autonomy to the provinces, as the Polish movement had hoped. However, it guaranteed basic civil liberties for the imperial subjects, including freedom of assembly and organization, thus giving the Council a legal basis for functioning.

Thus, in the last days of April, from a group of oppositionists, mostly intellectuals, operating under the guise of a newspaper, the Council became a powerful political organization with claims to represent the entire Polish people of the province and hence, in their view, the entire population, all the estates, from the aristocracy to the peasantry, and all denominations, from Christians of both rites to Jews. In the ranks of the National Council, they acted as representatives of various classes and religious groups of the united Polish people.

The Council Structure

As the Council stated in its first appeal, "our capital cluster will be connected with similar clusters… in all county towns" (Rada Narodowa, 1848, No. 1). Accordingly, in the following weeks, in late April – May 1848, local National Councils began to be formed in the province. Local councils were to coordinate the revolutionary movement on the ground; they could compose their wishes and recommendations to the Lviv-based Council and send their representatives. As a result, the Lviv Council adopted the name of the Central Council and now claimed the right to represent the interests not only of Lviv, but of the entire crown land.

At the time of its greatest rise in activity, in May 1848, the Council numbered up to 170 members. The Council did not have a single distinctive leader; its chairman was to be elected by its members by a simple majority of votes on a monthly basis. New members were to be admitted (co-opted) to the Council with the consent of at least three-fourths of the votes.

The location of the Council's seat is not completely clear. In the early days, it relocated often due to various obstacles from the government. The Council emerged in Tomasz Kulczycki's house. In the following days its members tried to meet in the refectory of the Dominican monastery, but there was an urgent need to deploy troops there. Then they tried to gather in the Ossolineum halls, where the Committee had met earlier, but the governor's office did not give permission for this, saying that these halls were already used as the seat of the Galician Credit Society.

Later, the meetings of the Council took place in the building of a theater, but it is not entirely clear which one. A modern Polish researcher of the Council's activities wrote about the Skarbek Theater as the seat of the Council (Stolarczyk, 1994). A Lviv historian from the nineteenth century, to whom he refers, repeatedly and unequivocally mentioned the "old theater" (in the building of the former Franciscan monastery on Teatralna street, which has not been preserved): general meetings of the Council are said to take place in the ballroom, while the committees used to gather in the side rooms (Schnür-Pepłowski, 1895). The version with the old theater seems more plausible, because at the same time, when the police blocked the seat of the Council on the governor's instructions on April 26 and 27, the governor himself was waiting for the arrival of the Galician Estates members and its opening, which traditionally took place in the Skarbek Theater; that's why the "new theater" could hardly be blocked. However, the Council's first appeal, drawn up on April 15 and then published twice in the newspaper on April 19 and 22, stated that the Council's newspaper could be subscribed to at the editorial office of the Dziennik Mód Paryskich (i.e. in the same Kulczycki's house) or in the "new ballroom" of the Skarbek Theater (Rada Narodowa, 1848, No. 1, 4). However, this may be evidence of the "travels" taken by the National Council around the city in the early days of its existence.

Internally, the Central Council was divided into separate committees or departments. The regional affairs department, headed by Leon Sapieha, dealt mainly with the introduction of the Polish language in the administration and courts and with the appointment of local Polish personnel there. The correspondence department, headed by Józef Dzierzkowski (later by Oswald Menkes), dealt with communication with local provincial councils, as well as with foreign delegations arriving in Lviv and the Council's own delegations to other regions: mostly to Vienna, Prague and Pest, but also abroad, to Paris and Frankfurt. The department of spirituality and science dealt with issues of education and comprised the clergy of all three denominations and representatives of intellectual labor, such as historian Karol Szajnocha. The budget of the Council was managed by a separate financial department, which included, from among more known people, Franciszek Smolka, the Dziennik's owner Tomasz Kulczycki and others.

Finally, a separate department dealt with the creation of the National Guard, which was conceived as the core of the future Polish army. The bulk of the volunteers consisted of Lviv students, petty gentry and burghers. In the summer, the Guard already numbered 4,000 people in Lviv and about 20,000 in the whole region, but they were rather poorly armed and performed mostly police functions. Its commanders were at first General Józef Załuski and later, most of the time, General Roman Wybranowski, both participants in the Napoleonic Wars and the Polish Uprising of 1830.

An Opposition to the Opposition: Peasants, Ruthenians and Conservatives

Having failed to resume the Galician Estates and realizing that direct repressive methods had no effect, the empire found a more subtle way to strike back. Although the Council claimed to represent all the peoples, religions and estates of the region, in practice significant social groups in the province remained outside its influence or even opposed its policies. There were three such groups in Galicia: the peasants, the Ruthenians, and the conservative aristocracy. Governor Stadion decided to take advantage of these differences and to "mobilize" his potential allies.

Peasants

The "peasant question" was one of the main ones during the Spring of Nations and, at the same time, one of the main dilemmas within the Polish movement. After several unsuccessful attempts at uprisings, it became clear that without the mass support of the peasants the nobility’s conspiratorial forces alone would not be able to overcome the rule of the empires. In the nineteenth century, Polish democrats consistently called for the abolition of serfdom and referred to peasants as their "brothers." From now on, in their view, the Polish nation consisted not only of the "gentry people", as in previous centuries, but of all social strata. The restored Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was now to be not a "noble republic" but a state of all the Polish people.

However, attempts to reform the Polish state even before its collapse did not affect Austrian Galicia. On the contrary, it was the "occupation" government that became the agent of change here. As early as the 1780s, Emperor Joseph II abolished serfdom in the empire: the peasants still had to work as serfs but gained personal freedom and became subjects of state law. Accordingly, recalling their position of having virtually no civil rights in the old Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Galician peasants had little motivation to support "noble" demonstrations (as they saw the beginnings of the Polish movement); rather, they were quite loyal subjects of the empire, which allegedly could protect them from their landlords' arbitrariness. This was most evident during the attempted uprising of 1846, when the peasants, frightened by the "noble revolt", sided with the empire.

In 1848, a real struggle between the Polish movement and the bureaucracy for the support from the peasantry unfolded in the countryside. Both "parties" tried to convince the peasants that it was their opponents who were more to blame for all troubles the peasants had to cope with. In addition, the Polish movement blamed the administration for the bloody events of two years before, which supposedly incited the peasants to rise against the rebels. In the structure of the Council, the peasant problem was dealt with by a separate committee, which tried to protect the peasants from the influence of the administration.

Both local democratic forces and emigrant circles called on the Galician aristocrats to abolish serfdom on their own, satisfying in this way the main need of the peasants. The National Council appealed to landowners in the first issue of its newspaper. Prince Adam Czartoryski, one of the most influential emigrants, proposed to do so symbolically on Easter, April 23.

Governor Stadion sensed the moment and managed to take the lead. On the eve of Easter, April 22, 1848, he arbitrarily — without the sanction of the emperor but on his behalf — announced the abolition of serfdom in Galicia. The emperor later approved these steps and signed the decree, backdating it to April 17. Thus, the Galician peasants were relieved of their duties a few months earlier than their counterparts in the rest of the empire, and again thanks not to potential national leaders but to the imperial administration.

Conservatives

Having deprived the Polish movement of a broad social base at the grassroots level, Stadion decided to cut off the conservative part of the elite from it as well. In matters of compensating for the lost labor power and sharing of forests and pastures that came to the fore in the countryside after the abolition of serfdom, the revolutionaries' program differed greatly from the position of many large landowners. Some of them did not agree to radical social changes, such as the abolition of all class privileges, the political equality of all citizens, which radical democrats sought. In the confrontation between the Council and the governor, they remained on the side of the latter.

On May 3, a week after the "self-dissolution" of the Galician Estates, a group of conservative aristocrats, who were loyal to the government, created, with the sanction of the governor, the Landowners' Association. In their program, they combined Polish patriotism and social conservatism. There was a heated controversy between conservatives and revolutionaries in their press. Conservatives accused the revolutionaries of destructive policies, while representatives of the Council accused them of collaborating with the government.

Divided by social and political issues, both camps were nevertheless united in the national question: both wanted greater rights for the Polish people (though often interpreted the latter differently) and culture in Galicia; both considered the local Ruthenians only a separate branch of the united Polish people.

Ruthenians

Of all the external problems of the Polish movement, the Ruthenian was the main one since it undermined Polish national "monopoly" over Galicia and other Ruthenian territories of the ancient Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Most members of the Polish movement perceived the Ruthenians only as a peculiar confessional and ethnographic group within a single Polish nation, denying them the right to a separate political voice. During the first half of the nineteenth century, as in the first month of the revolution, the Polish movement was indeed the only national political movement in Galicia and in Lviv, and even some of the Ruthenian intelligentsia took part in it. However, in the age of romanticism and fascination with folklore, the fact that the vast majority of the population in the east of the province (mostly peasants) spoke a different language and belonged to a different rite, other than most revolutionaries (mostly gentry and intellectuals), became increasingly significant in both political and social terms.

Back in March, during the first demonstrations, some of the Ruthenians present were outraged that the text of the petition did not mention them as an equal national community within the province. Members of the delegation to the emperor later rectified this shortcoming, realizing the possible damage, and the National Council published appeals to the Ruthenians calling for fraternal cooperation. Nevertheless, the general attitude of Polish activists to the Ruthenian issue could not change so quickly. Stadion decided to take advantage of these national differences and prompted the loyal Ruthenian hierarchs to lead their national movement, which was just beginning to assert itself. As a result, the Supreme Ruthenian Council, an alternative to the Polish one, emerged in Lviv in early May. Having been confronted with an alternative, the Central National Council, which had been the only one of its kind in Galicia, now became the Polish Council, one of two competing national representations in the province.

It is noteworthy that both organizations, which were in opposition to the National Council — both the Ruthenians and the landowners, — arose just a week after the governor was defeated in the matter of the Galician Estates, and the constitution was promulgated in Vienna that allowed organizations to be formed freely; both organizations were headed by people belonging to the governor's advisory council (the so-called Beirat).

Back in May, the Polish Council created its own alternative to the Supreme Ruthenian Council, an organization called the Ruthenian Congress, or Sobor. It consisted mainly of Ruthenians loyal to the Polish movement, who, in many cases, belonged to the Polish Council earlier, as well as of Poles, including aristocrats, who recognized their Ruthenian origins. However, the Ruthenian Congress did not achieve any significant success, although promoting some interesting ideas, and in early October it fully joined the National Council.

The Supreme Ruthenian Council, instead, mirroring the Polish one, created a regional network of county councils. These Ruthenian councils, like Polish ones, fought for influence over the peasants; however, due to the cultural reasons already mentioned, it was them who gained more success. The Supreme Ruthenian Council sought to divide Galicia into a western, Polish part centered in Krakow and an eastern, Ruthenian part, whose capital was to remain Lviv. Such a demand threatened the future of Polish Lviv, which the Polish movement saw as the capital of its national province. In the summer of 1848, both camps organized mutual campaigns to collect signatures for and against the partition of Galicia: by the end of the year, the Supreme Ruthenian Council had collected almost 200,000 signatures, while the Polish Council had about three times less.

The two camps met at the Slavic Congress in Prague in June 1848, where a Polish delegation consisting of over a dozen people headed by Jan Dobrzański, Tytus Dzieduszycki, Jerzy Lubomirski and others participated. The Congress aimed to resolve local misunderstandings and develop a common position of the Slavs in the face of the threat of Vienna's centralism restoration, on the one hand, and the danger of German and Hungarian nationalisms claiming some Slavic territories, on the other hand. The Austrian Slavs wanted to reformat the monarchy into a federation of national provinces united under the Habsburg scepter, where the Slavs would have taken an equal position with the Germans and Hungarians.

In this situation, the Polish movement took an ambiguous position. On the one hand, it also opposed Vienna's centralism, while, on the other hand, the Poles were interested in the idea of an Austrian federation only as a transitional stage on the way to the restoration of the Commonwealth. For them, the empire was not a barrier against the encroachments of competing national movements, but a major obstacle to achieving their main goal. In addition, the main national opponent of the Poles within the empire suddenly became not the Germans or Hungarians but the Slavic Ruthenians.

The Polish-Ruthenian conflict was almost the only inter-Slavic misunderstanding within the monarchy, and one of three separate sections of the congress was set up to discuss it. Through the Czechs, both delegations managed to reach a compromise: the Polish side recognized the equal national rights of the Ruthenians in Galicia, while the Ruthenian side agreed to postpone the division of the province until it is considered in the future parliament. However, due to the outbreak of an uprising in Prague, the activities of the Congress had to be stopped ahead of schedule, and the compromise reached, which in fact did not satisfy either side, was never implemented.

As a result, the idea of dividing Galicia was never realized, so in this matter the Polish movement won, maintaining political control over the united province until the very end of the empire.

Social Issues and the Crisis of the Council

In late June, the Austrian monarchy held its first parliamentary elections. Representatives of the National Council won all three seats for Lviv — Count Leszek Dunin-Borkowski, Florian Ziemiałkowski and Marian Dylewski — and a total of 42 out of 100 "Galician" seats.

The Polish democrats formed their own faction in parliament, which took seats in the left, "revolutionary" wing of parliament. Landowner Seweryn Smarzewski was elected its chairman, although the de facto leader and most influential Polish figure in parliament was Franciszek Smolka, who became vice-president of the Austrian parliament in September and headed it in October. Although the Polish Council won almost half of the "Galician" seats, it did not gain a decisive influence over its own peasantry, which found itself together with representatives of the Ruthenian Council in the pro-government "center" headed by the main "enemy" of the National Council, the former Governor Stadion. The other opponents of the Council, the Galician conservatives, were seated in the right, "reactionary" wing of parliament.

Two main issues discussed at parliamentary sessions were the abolition of serfdom (which had been accomplished only in Galicia by that time) as well as the compensation to landlords for it, and the question of the future constitution, including the expansion of the right to vote. Both issues revealed certain contradictions that existed between the representatives of the National Council themselves.

Thus, back in June, at the pre-election meeting held in the Ossolineum, where candidates for Lviv parliamentary constituencies were chosen (a kind of internal "primaries" within the Council), the issue of suffrage was discussed. As throughout the continent, the question was whether to grant the right to vote to the entire population, regardless of status or education (democratic or radical ideas), or to still limit it by certain material or educational qualifications (liberal ideas). One of the contenders, Leszek Dunin-Borkowski, called for restricting suffrage by "intelligence," another called for restricting it at least by literacy, while the third one, Marian Dylewski, called for leaving people "something they could fight for themselves", since they would not appreciate and would lose quickly anything that was merely granted to them. The newspaper Dziennik Mód Paryskich, which was at the origins of the National Council at one time and was published by its representatives later (edited by Karol Szajnocha), criticized all of them from radical democratic positions.

Similarly, already in parliament, when it came to voting for compensation due to the landlords for serfdom they had lost, most representatives of the Council, including Dunin-Borkowski, Zemiałkowski, and others, faithful to their democratic postulates, voted against such a compensation together with peasant members of parliament. Instead, Bishop Wierzchlejski, despite the fact that he once supported the Council and formally belonged among its members, voted for it from a conservative position. One of the leaders of the Council, Franciszek Smolka, abstained from voting at all, which is why the issue was finally resolved against the benefit of the peasants.

These cases demonstrate certain ideological differences within the ranks of the National Council itself. Becoming a "nationwide" political platform, it brought together people with very different views on the political and social situation, united only by their devotion to the Polish national cause and opposition to the government. In the first months of the revolution, when the main front lay between the imperial government and national oppositions, this common denominator was sufficient for some united activity. Later, however, when it came to specific issues and decisions, the difference of opinions became more apparent.

In addition, after the election of parliament, the main center of political struggle moved to Vienna. After Governor Stadion, who represented the "old regime" for the revolutionaries, was recalled from Lviv in June, tensions in the city eased a little. In the following months, the governor's duties were performed by Agenor Gołuchowski, and the new governor, Wacław Zaleski, arrived in the city for a short time in late October. Both were the first Poles in this position. Although they distanced themselves from the Council's overly reformist program and belonged rather to the conservative camp, they could not be called "intruders" or accused of Germanizing the region. As Karol Szajnocha wrote back in May, "no one in Lviv persecutes anyone, no one interferes with anyone, so there is no activity and nothing to say about."

As a result, the activity of the National Council gradually declined: in late June its meetings were attended by about 40 people and by an average of just 30 in July. In autumn there was much talk about the decline of the Council and the need to reorganize it and to fill it with some new purport. Józef Dzierzkowski, one of the founders of the revolutionary movement in Lviv, even suggested convening a nation-wide regional congress in Lviv, which would define a new program of activities and breathe new life into the Council. Others argued that the program was long defined and quite clear, so it was only necessary to implement it more effectively, and not to engage in idle talk. However, no concrete results were ever reached.

Liquidation of the Council and its Significance

In this lull, it was radical voices that were gaining more and more weight. The Paris-based Polish Democratic Society sent its representatives to Lviv immediately after the outbreak of the revolution; however, emigrants were not allowed to participate in the Council. On the one hand, this could be a reason for the government to abolish the Council; on the other hand, the Galician revolutionaries, taught by the events of 1846, did not accept the excessively radical slogans and methods of struggle promoted by the emigrants.

Instead, the radicals found considerable support among the urban lower classes and the student youth organized in the so-called Academic Legia. The situation became especially tense in October 1848 during another uprising in Vienna. According to one version, after the defeat of the Vienna uprising, the Austrian military command provoked a riot in Lviv purposely, in order to suppress all radical forces in the city under this pretext and, at the same time, to eliminate the opposition. When, on November 1, after another clash between protesters and troops, radicals seized the city hall and built barricades around the Rynok square, members of the National Council tried unsuccessfully to persuade the rebels to lay down their arms. On the following day, November 2, government troops suppressed the uprising and imposed martial law in the city. All societies, including the Central National Council, were abolished.

The short, six-month-long activity of the National Council in 1848 did not become a global break for the Polish national movement, as, perhaps, for other Slavic peoples of Austria, i.e. the same Ruthenians, Czechs or Slovaks for whom the Spring of Nations was a political debut. The Polish problem was on the international agenda both before and after the revolution. However, the National Council ushered in a new stage in the history of the Polish movement in Galicia: in 1848, Polish revolutionaries, defeated two years earlier by their own peasants, for the first time replaced the slogan of an uncompromising struggle for the revival of independent Poland with more pragmatic demands for Polish administration in Galicia without an immediate separation from the empire, and armed methods of struggle with a legal political struggle against the government.

Thanks to the Council's activity, the Vienna government also realized that the Polish factor in Galicia should not be ignored. In the decade following the resumption of absolutism, the province was governed by Agenor Gołuchowski, one of the leaders of the Polish conservative camp. Although he was on the other side of the barricades with the revolutionaries in 1848, his rule was in fact a transitional stage in the future acquisition of autonomy by the Galician Poles. In the early 1870s, conservative Gołuchowski was the governor of autonomous Polish Galicia, democrat Zemiałkowski was president of self-governing Lviv, and liberal Smolka was later president of the constitutional Austria's House of Deputies. The ideas, first formulated in 1848 by the Central National Council, were implemented in one and a half to two decades by efforts and compromise between the two Polish camps and thus laid the foundation for the future development of Lviv as the capital of the Polish autonomy within the Austrian Empire.

Related buildings and spaces

People

Franciszek Smolka — the probable initiator and one of the founders and leaders of the Central National Council, leader of the Polish faction in the Reichsrat, president of the Austrian parliament from October 1848 and, later, president of the House of Deputies of the Austrian Empire.Jan Dobrzański — a writer, editor of the newspaper Dziennik Mód Paryskich, one of the founders of the Central National Council, editor of its press organ Gazeta Narodowa.

Florian Ziemiałkowski — one of the founders of the Central National Council, a deputy to the Austrian parliament for Lviv and, later, president of Lviv.

Józef Dzierzkowski — a writer, one of the founders of the Central National Council.

Leon Sapieha, prince — a member of the Central National Council, the Ruthenian Council, the Advisory Council; later, Marshal of the Galician Provincial Sejm.

Aleksander Fredro, count — a writer, a member of the Central National Council.

Leszek Dunin-Borkowski, count — a writer, a member of the Central National Council, a deputy to the Austrian parliament for Lviv.

Marian Dylewski — a member of the Central National Council, a deputy to the Austrian Parliament for Lviv.

Karol Szajnocha — a historian and a writer, a member of the Central National Council, editor of the newspaper Dziennik Mód Paryskich (later, Tygodnik Polski).

Franciszek Wierzchlejski — Roman Catholic bishop of Przemyśl, a member of the Central National Council, a deputy to the Austrian Parliament and, later, Archbishop of Lviv.

Onufriy Krynytskyi — a Greek Catholic priest, a member of the metropolitan consistory in Lviv, one of the founders of the National Council, represented the Ruthenians of the Greek (i.e. Eastern) rite in the Polish movement.

Mykola Ustyyanovych — a Ruthenian poet who supported the Ruthenian Triad, (probably) one of the founders of the National Council, later a member of the Ruthenian Council, the initiator of the Congress of Ruthenian Scholars.

Oswald Menkes — a lawyer, one of the founders of the National Council, later chairman of the Correspondence Department, a member of the City Department.

Roman Wybranowski — a general, former participant in the Napoleonic Wars and in the Polish uprising of 1830, commander of the National Guard in Lviv in 1848.

Franz Stadion — Governor of Galicia, the main political opponent of the Council, a deputy to the Austrian Parliament, later Minister of the Interior of the Austrian Empire.

Sources

- Włodzimierz Borys. Wybory w Galicji i debaty nad zniesieniem pańszczyzny w parlamencie wiedeńskim w 1848 r. Przegląd Historyczny 1967 58/1, 28-45.

- Jana Osterkamp (2016) "Imperial diversity in the village: petitions for and against the division of Galicia in 1848", Nationalities Papers, 44:5, 731-750

- Antony Polonsky, "The Revolutionary Crisis of 1846-1849 and Its Place in the Development of Nineteenth-Century Galicia", Harvard Ukrainian Studies, Vol. 22, Cultures and Nations of Central and Eastern Europe (1998), pp. 443-469

- Rada Narodowa. №1-30. Lwów, 1848

- Marian Stolarczyk. Działalność Lwowskiej Centralnej Rady Narodowej. Rzeszów, 1994.

- Stanisław Schnür-Pepłowski. Z przeszłości Galicyi (1772-1860). Lwów, 1895.

- Rok 1848. Wiosna Ludów w Galicji (po redakcją Władysława Wica). Wydawnictwo Naukowe AP. Kraków, 1999.