The Landowners' Society

History

Table of Contents

1. Origins and Preconditions

2. Initiators and Founders

3. Political Program

4. Confrontation with the National Council

5. The End of the Revolution and Its Consequences

Origins and Preconditions

[Up]The Landowners' Society was an organization of the Galician aristocrats' conservative wing.

Aristocrats in Galicia descended mostly from the ancient magnate families of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, who had owned substantial landed estates and confirmed their nobility in the Austrian Empire, sometimes even getting court titles. Having become Austrian princes and counts, the Galician magnates nevertheless kept their ancient Polish consciousness.

All their political activity in the previous decades was rather limited. They participated in the meetings of the Galician Estates, a body having very narrow, rather advisory functions. The real power in the province was in the hands of the Vienna-appointed bureaucracy, which thus became the main political opponent of the local elites. However, sitting in the Estates, local aristocrats continued to retain a monopoly on the right to speak on behalf of the Polish people in Galicia and at the same time on behalf of the entire population of the region.

Meanwhile, it was the supporters of democratic ideas and revolutionary methods who were increasingly taking the initiative in the Polish national movement. In addition to national liberation, there were also radical social changes at the core of their program. It included the abolition of serfdom, the elimination of class privileges, equal rights for all, and so on.

This obviously was against the interests of the aristocracy. Some of the aristocrats were well aware of the need for reforms, but sought to carry them out with minimal losses to themselves. Others, on the contrary, began to lean towards conservative views in response to the threat of a social revolution.

The aristocrats supported exclusively legal political methods and opposed significant social changes. They saw themselves as the basis of the social order and the world's moral structure. They would have liked the government to share power in the region with them. But, according to the old worldview, they did not consider it necessary to share that power with the general public (as sought by the new currents of liberals and democrats).

The failure of the uprising in Galicia in 1846, which was initiated by the radical democrats and resulted in a massacre of landlords by peasants, further pushed the aristocrats to seek compromises with the authorities.

Therefore, the aristocracy did not act as a monolith in the face of the social challenges. It tended to two different worldview poles: liberal and conservative.

After the outbreak of the revolution, both camps pursued very different policies. While liberal aristocrats joined the movement initiated by the liberal and democratic intelligentsia seeking to partially assume a leading role in it, the future founders of the Society initially withdrew from taking any active position. During the first demonstrations in Lviv they were absent from the signatories of the petition to the emperor. Some of them even went on their own delegation from Galicia to Vienna, which was organized separately from the revolutionaries. Later, they did not participate in the National Council.

Some of them, instead, joined the Beirath along with other forces loyal to the government. This was an advisory council arranged by the governor in opposition to the National Council; it was to assist him in administering the province. However, the Beirath, created on April 29, proved to be ineffective. The governor was apparently uninterested in giving it real powers, so, as Leon Sapieha later recalled, "it all ended with us meeting with the governor a couple of times a week to have a cup of tea." In addition, it was the governor who, acting in advance, initiated the liquidation of serfdom, thus affecting the landowners' interests.

All this prompted the conservative aristocrats to form their own institution just a few days later, on May 3, 1848, one that would defend their corporate interests. The organization was called the Society of Owners of Large Land Estates, abbreviated as the Landowners' Society.

Initiators and Founders

[Up]Count Gwalbert Pawlikowski initiated and chaired the Society. He was the founder of a large library and natural collection in his estate at Medyka and a former curator of the Ossoliński Institute. It was him that Prince Ossoliński once entrusted with transporting his assets from Vienna to Lviv.

Besides Pawlikowski, among the most famous members of the Society were prince Karol Jabłonowski, who had been one of the initiators of the Beirath and was then curator of the Galician Savings Bank, and Kazimierz Badeni, the grandfather of the future governor and prime minister. In total, about 120 members joined the Society during the summer. They belonged to different generations, from 72-year-old veteran Cyprian Komorowski to relatively young 30-year-old Edward Stadnicki. Generational differences did not play a role in the political orientations of the aristocracy.

Such well-known aristocrats as Leon Sapieha or writer Aleksander Fredro did not join the Society. Despite the seemingly common interests with the Society's representatives, they joined the National Council, where they represented a moderate liberal wing. Leszek Dunin-Borkowski, another well-known aristocrat and a romantic writer, was mentioned among the members of the Society at first, however he moved later to a much more democratic position.

Apparently, the main political figure among the Society members was Agenor Gołuchowski. As early as the early 1840s, he began a bureaucratic career at the governorate, making an untypical step as for a Galician aristocrat of the time. After the events of 1846, he became one of the closest persons to Governor Franz Stadion. In particular, he was one of the developers of a version of agrarian reform, which was supposed to protect landlords from excessive losses. After the governor left Lviv in the summer of 1848, it was Gołuchowski who actually headed the civil administration in Galicia.

In addition to conservative views and loyalty to the government, the founders of the Society were united by two other things. Firstly, almost all of them at the same time belonged to and formed the basis of the Galician Agricultural Society (Galicyjskie Towarzystwo Gospodarskie). Created at the Galician Estates three years before the revolution, it aimed to "encourage economic growth in the region through the expansion of useful knowledge and thus promote the government's charitable intentions," therefore combining the principle of organic labor and loyalty to the government. Along with the Galician Savings Bank to which the Society's members were also directly related, these were the first regional institutions to involve local elites in the economic management of the region.

Secondly, as owners of large estates in the provinces, almost all of them (except for the official Gołuchowski) lived permanently outside Lviv. The Society's charter even stated that each of the members who was in Lviv at an appropriate time had the right to represent it. In their publications, the aristocrats proudly called themselves "quiet villagers" and pointed out that their responsibilities of the Society members were to be combined with the "duties of the landlords," which imposed a special responsibility on them in the "present crisis."

It is unknown whether it was also economic issues that prevented half of the 120 members from coming to Lviv on September 6 for the first (and, as it turned out, the only) general congress of the Society. The official periodical explained this by various obstacles from opponents and the remoteness of most members from the city. Meetings were held for three days in the Skarbek Theater, where the Society's office was also permanently located. Count Skarbek, who died a month later, entrusted one of the Society's leaders, Karol Jabłonowski, to oversee his foundation.

Political Program

[Up]Judging by its name, the Society initially positioned itself as a non-political class corporation. But it started drifting more and more towards being a political organization during the summer. Moreover, it tried to engage people from outside their own social stratum who were prone to conservatist views, including industrialists, rich burghers and intellectuals.

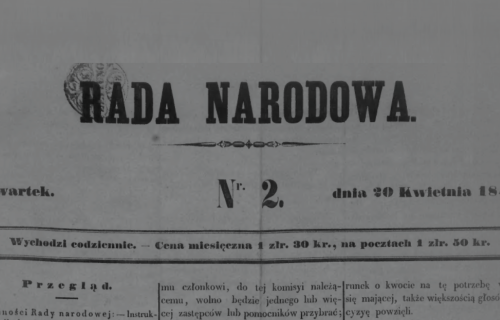

Therefore the Society started its own periodical under a manifest non-corporate name Polska in August 1848. Hilary Mieciszewski, a publicist from Krakow, became its editor-in-chief. Its editorial office was located in the building of the Winiarz bookstore at the corner of pl. Rynok and ul. Dominikańska (now vul. Stavropihiyska).

The periodical's program article suggested that the Galician Poles support the liberal government in the empire and its undertakings, legally seek to expand national freedoms, further build up national institutions in the region and through these freedoms and institutions go to the future union with their Polish brothers from other divisions.

In fact, the aristocrats sought to remove the German bureaucracy from governing the region and take its place themselves. In this way, they hoped to help Galicia regain its ancient Polish character. In their view, Galicia was to be an essentially Polish national province within the Habsburg Empire under the rule of the local aristocracy. The revival of independent Poland, which had been lost due to the "negligence and carelessness of our fathers," was not mentioned directly, being postponed thus until more favorable times.

As regarding social questions, they did accept the abolition of serfdom, which was already a fait accompli. But they viewed this act as a confiscation of their property and therefore demanded compensation (which was a common practice for landowners at that time). In addition, they did not wish to sever patrimonial relations with their former subjects or, even more so, to give them political rights. Despite the freedom from serfdom, aristocrats thought it better for the peasants to remain under their paternal care as they supposedly knew better how to ensure social welfare and progress.

This program contradicted multiple theses of the National Council. The latter followed legal methods too but did not oppose the empire directly. It declared the revival of Poland as its ultimate goal openly, sought concessions to peasants in the issue of compensations and equal civil rights for the entire population, as well as political rights being extended at least to burghers and the intelligentsia (there was no unequivocal position on peasants here).

Confrontation with the National Council

[Up]Entering the public arena with such a program made Society the main competitor of the National Council in the Polish national camp in Galicia and provoked a fierce open conflict between the two organizations. The Society's refusal to submit to the Council effectively undermined the latter's hitherto undisputable monopoly on leading the Polish movement in Galicia.

The Council accused the Society of cooperating with the authorities and of actual betrayal of national interests for personal gain. It emphasized the collaborative nature of the Society, calling its members the "bajratowicze" (from the name of the governor's advisory council in Polish spelling). In response, the Society stated that it did not recognize the legitimacy of the Council, as the latter was not approved by the government but just tried to usurp the leadership of the Polish movement "by the grace of the street."

The conflict erupted in stormy epithets in the press. One of the leaders of the Council, Józef Dzierzkowski, a writer of rather radical views, called the conservatives "Circassians, Kalmyks, half-lords, thieves, spies, scoundrels, traitors." Those were somewhat more restrained in their response, saying that the then democrats were in fact "ochlocrats," who led to social degradation, and calling the current situation in the empire "pseudo-freedom."

They accused their opponents of artificially dividing the hitherto united Polish nation into "democrats" and "aristocrats" as they allegedly called all their opponents. The conservatives, on the other hand, used the very name of their periodical to appeal to the internal unity of the Poles — apparently, under their own domination.

However, the Society's attempts to gain popularity in society were unsuccessful. Local centers were developed only in the eastern part of the province, where there were more large landholdings and therefore the magnates had more influence. The general public, on the other hand, saw the Society as a reactionary force, the latter even complaining that it was "anathematized from everywhere."

In mid-October 1848, as the situation in the empire deteriorated, this led to what is believed to be the first political strike ever in Lviv. The employees of the Piller's printing house, where all the newspapers of that time were published, refused to print the Polska journal for a week. However, there was no such attitude towards the Krakow conservatives, who did not "stain" themselves with direct cooperation with the government.

Two years earlier, Krakow had been annexed by the Austrian Empire and incorporated into Galicia, which in this way got another powerful city center near Lviv. Krakow was already becoming the main intellectual center of Polish conservatism at that time although it retained its previous revolutionary halo of two years before.

Unlike their Lviv colleagues, leaders of the Krakow conservatives took an active part in the Slavic Congress in Prague and were elected to the parliament in Vienna. Some of them even, despite differing views, participated in a joint delegation to the emperor in the spring of 1848 along with the revolutionaries. There was no noticeable close cooperation between the two conservative groups in Galicia. Although the editor-in-chief of the Lviv conservative journal had come from Krakow, the leaders of the Krakow community themselves did not join the Society in Lviv.

Unlike active Krakowians, the Lviv conservatives were not represented in parliament, This way their main political asset was Gołuchowski's influence on the regional administration, as well as the goodwill of the newly appointed Governor Wacław Zaleski.

The End of the Revolution and Its Consequences

[Up]The conservatives perceived the defeat of the uprising on November 1 in Lviv and the consequent liquidation of the National Council as a confirmation of their own moral reasoning and the rightness of their chosen strategy. Allegedly, they had always warned that "the road, which all public life in the region had set foot on, would lead to just such a result." After the imposition of martial law in Galicia, the Society, like other loyal organizations, was not dissolved and continued to publish its periodical for some time.

Interestingly, it was not until December 1848, after the removal of their main internal opponents (the National Council), that the Polish conservatives openly criticized the Ukrainian movement for the first time. The Ruthenians, they claimed, could not be considered a full-fledged nation, because they did not have a developed written language (the fact they admitted themselves) and were represented only by peasants and priests who "in their Ruthenia" seek to take the place of the aristocracy, which the Society's members, apparently, preferred to keep for themselves. The Ruthenian Council held a similar loyalty to the government but undermined the national monopoly of the Poles in the region. The Society's periodical did not notice this during the revolutionary months.

Nevertheless, later, after the end of the revolution and its challenges and a return to absolutism, the continuation of the Society's activities lost its meaning. Although it is unknown whether the Society ceased to exist formally, its members continued to be actively present in the life of the city and the province. After the revolution most of the leading members of the Society returned to their work in the most important economic institutions and various initiatives. For example, Karol Jabłonowski and Maurycy Kraiński took an active part in the construction of the railway to Lviv, while Włodzimierz Russocki was engaged in the creation of the Society of Friends of Fine Arts in Lviv.

For the conservatives, the main challenge of the Spring of Nations was the first and bright manifestations of new political practices: the participation of the masses in political life, street demonstrations, mass daily press, parliamentary elections and more. They were not ready for these drastic changes and initially did not wish to put up with them but gradually had to adapt. Needing to legitimize their position and to find support among new political actors, they tried — perhaps, for the first time ever — to speak to other strata of the population, thus evolving from a purely class corporation to an ideological political union.

Ideologically, the conservatism of landowners was not yet "programmatic." It was rather their natural worldview reaction to the rapid changes taking place around. They found their ideal in the ancient Polish society, where they had been the unconditional and only sources of authority, and did not wish to accept the new, modern vision of Poland, which eroded this ancient monopoly and increasingly emerged among the liberals and radicals.

In January 1849, Agenor Gołuchowski was appointed governor of Galicia and started to gradually implement the Society's political program, later becoming the chief "architect" of Galician autonomy. The autonomous status gave dominance in the land to the aristocracy but also granted political rights to wider sections of the population in accordance with the property qualification, this becoming a compromise between the conservative and liberal programs. Beginning from 1848, Lviv and Krakow conservatives can be considered the predecessors of the Podolacy and Stańczycy — conservative groups, which largely determined the Galician politics of the constitutional era, competing and interacting in Lviv as the provincial capital.Related Stories

Related Places

Vul. Lesi Ukrainky, 01 – Maria Zankovetska Theater (former Skarbek Theater)

Show full description

Personalities

Gwalbert Pawlikowski — Chairman of the Society, a collector and bibliophile, former curator of the Ossolineum.

Agenor Gołuchowski — one of the leaders of the Society, actual head of the civil administration of Galicia in 1848, governor of Galicia from January 1849.

Karol Jabłonowski — one of the leaders of the Society, vice chairman of the Galician Savings Bank, manager of the Stanisław Skarbek Foundation (including the theater).

Maurycy Kraiński — deputy chairman of the Society, a member of the committee of the Galician Business Association.

Hilary Mieciszewski — a Krakow publicist, editor of the Society's periodical Polska.

Organizations

Sources

- Kazimierz Karolczak, "Arystokraci galicyjscy wobec wypadków 1848 r.," Rok 1848. Wiosna Ludów w Galicji (pod redakcją Władysława Wica), (Kraków: Wydawnictwo naukowe AP, 1999);

- Bogdan Szlachta, "Konserwatyści galicyjscy w okresie Woisny Ludów (próba zarysu)," Krakowskie Studia z Historii Państwa i Prawa 3, 2012, 255-263;

- Kazimierz Adamek, "Geneza i wstępny program krakowskiego "Czasu"," Kwartalnik Historii Prasy Polskiej, 19/1, 1980, 19-34;

- Polska, Pismo poświęcone rozprawom polityczno-ekonomicznym i historycznym, krajowym i zagranicznym, 1848;

- Gazeta Narodowa, 1848.