The Ruthenian Congress

A political organization that functioned in Lviv in May-October 1848, during the Spring of Nations in Lviv. Founded on the initiative of the Polish Central National Council, it positioned itself as the true representative of the Ruthenians (Ukrainians) of Galicia as opposed to the Supreme Ruthenian Council. It sought either to integrate the Ruthenians into the Polish national movement or to unite the two movements in a political union. As the Congress failed to gain widespread support, it later joined the Polish National Council.

History

The Congress represented people with a dual Polish-Ruthenian identity. These were both Poles of Ruthenian descent, and Ruthenians committed to Polish ideas and culture. Unlike its opponents, it offered its own vision of the "Ruthenian people", one beyond denominations and socially undivided. Later, the Ukrainian national movement in Galicia appropriated some of the ideas of the Congress.

Preconditions

Beginning from the first revolutionary days in March 1848, the revolution in Lviv was led by the Polish movement or rather its liberal wing. The latter was represented mostly by the intelligentsia and the moderate nobility who united within the Central National Council. Until then the Polish movement had been the only political national movement in Galicia and united people of different origins and denominations. Using liberal social slogans, it advocated the introduction of constitutional freedoms and the restoration of an independent Poland (in the future) or at least the widest possible Polish autonomy within Austria (as the immediate goal). The key criterion for joining this movement was not so much ethnic or confessional affiliation. It was rather the opposition to the current conservative regime and adherence to the ideas its members professed, in particular to the idea of the Polish statehood. Of course, joining this movement was usually accompanied by acculturation in or at least sympathy for Polish culture.

There were numerous Ruthenians who joined the Polish movement. Their awareness of their own cultural, ethnic or religious differences did not prevent them from manifesting solidarity with the Polish demands or even imagining themselves in terms of belonging to a single Polish political nation. Instead, the Supreme Ruthenian Council, established on May 2, and a petition issued by its leaders on behalf of the Ruthenian people as early as April 19, proclaimed for the first time not only a cultural but also a political separation of the Ruthenians from the Poles and, at the same time, their unconditional allegiance to the Austrian throne and government. Both the petition and the newly formed Council originated within the highest ranks of the Greek Catholic Church, which was closely cooperating with the government at that time.

According to the opponents, the emergence of a separate Ruthenian Congress with its own program, firstly, broke apart the hitherto single national and revolutionary camp, secondly, in the revolutionary conditions, placed the newly born Ruthenian movement on the same side with the reactionaries, and thirdly, it subordinated this movement to the conservative church hierarchy instead of the progressive seculars. It was these claims to the Supreme Ruthenian Council that prompted various people to found an alternative representation of the Ruthenian people in Galicia. They aimed to be more secular and not to sever ties with the Polish movement, and to be in opposition to the government together.

Origin and Organization

The shaping of the organization was going rather sluggishly. It was only on May 23 that the first constituent assembly of the so-called "Polish-Ruthenian Council" took place, in the ballroom of the Skarbek Theater. The name "Ruthenian Congress" appeared later; it was only the second public meeting on June 3 which was held under this brand. It was only on June 8, almost a month after its formation, when the charter of the Congress was published. The charter contained only three short clauses. It defined the purpose of the activity, the procedure for electing the chairman and two deputies (they were to be elected every two weeks) and the grounds for membership in the organization. The purpose of the Ruthenian Congress, as was stated in the charter, was to nurture the Ruthenian people, to contribute to their free development and at the same time to maintain consent and unity with the "fellow people of our common homeland," that is, the Poles. On the same day, the first appeal was published on behalf of the Congress: "Ruthenian Brothers!," stating its basic views and arguments. It was signed by 64 people, which is only two signatures less than the similar appeal of the Supreme Ruthenian Council of May 10.

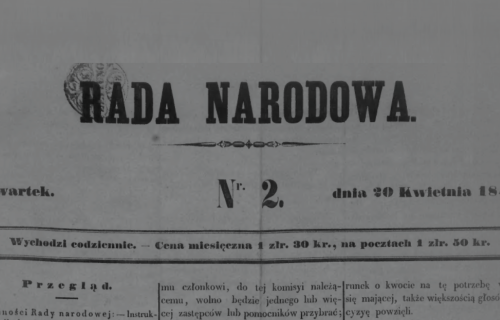

It was various appeals — to the "dear peasant brothers," to the "reverend priests," to the "Ruthenian intelligentsia," etc. — that became the chief means of communication between the Congress and the public. They were published at first as separate leaflets in the Ossolineum printing house. The most important ones were later reprinted in the newspaper Dnewnyk Ruskij ("The Ruthenian Daily"). In addition, members of the Congress published their own pamphlets, sometimes anonymous. Initially it was in the Polish newspapers Gazeta Narodowa and Dziennik Narodowy. Some, to emphasize their commitment to the Ruthenian cause, published them in the Zoria Halytska, the official periodical of their opponents in the Supreme Ruthenian Council.

The newspaper Dnewnyk Ruskij, the official periodical of the Ruthenian Congress, was founded in mid-August. Nine issues came out during the months of its existence. It was published in Michał Poręba's printing house, its editor-in-chief was Ivan Vahylevych. The newspaper, same as the appeals, was published in the Ruthenian language, quite close to the vernacular, but in the Latin alphabet with Polish spelling. Three issues of the newspaper were also duplicated in Cyrillic. At first, the authors of the appeals explained their choice of the Latin alphabet by the lack of Cyrillic fonts in Lviv. Later, in the first issue of the newspaper, they emphasized the fact that many Ruthenians to whom the editorial board planned to appeal did not read Cyrillic. They perceived Cyrillic rather as a traditional sacred script, intended more for ecclesiastic use. Both the Congress founders, as well as the public they intended to reach, were mostly secular people and acculturated in the Polish environment.

People and Milieus

Grounded in the traditions of the ancient Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the aristocrats combined loyalty to their "small" homeland of Ruthenia and the "large" political homeland of Poland. The dual (or two-tiered) identity they had adopted — gente Rutheni, natione Poloni, or "Ruthenians of the Polish nation" — allowed them now, in the wake of national movements and the gradual democratization of politics, to "restore" their allegedly lost connection with their people and to retain the right to speak on behalf of the latter in the new national realities. At the same time, they did not sever ties with their real political and cultural community, the Poles.

The secular intelligentsia who joined the Congress, associated Polish culture and consciousness not so much with the legacy of the ancient "common homeland" but rather with the latest liberal and democratic ideas. Coming mainly from the Ruthenian provincial milieu, they embraced attractive ideas of constitutional freedoms and national solidarity mostly clad in the "Polish kontusz." The adoption of the dual identity allowed them to adapt family origins to cultural orientations and political views, that is, to adapt their past to their own vision of the future. Concurrently, it served as a way to involve their Ruthenian "fellow compatriots" in modern political life without denying them the right to their own local culture and identity.

Former participants of the Polish conspiracy from the times of the 1830s-1840s uprisings made up another category of the Congress members. Mykhailo/Michał Popiel (a small landowner from Kulchytsi, a Greek Catholic), Julian Horoszkiewicz (Leon Sapieha's personal secretary at the time of the revolution) and Kasper Cięglewicz wrote poetry and appeals in Ruthenian addressed to Galician peasants in the 1830s, calling for support for the Polish insurgents. In the course of their previous activities, all of them even spent several years each in the notorious "political" prisons Kufstein and Spielberg, so their commitment to the Polish cause was especially important to them.

However, not all active members of the Polish movement with Ruthenian roots joined the Congress. The owner of the pro-revolutionary newspaper Dziennik Mód Paryskich Tomasz Kulczycki and its editor Jan Dobrzański, one of the leaders of the first days of the revolution in Lviv did not join it. The latter, for tactical reasons, declared himself a Ruthenian at the Slavic Congress in Prague in June 1848 (in order to increase the representation of pro-Polish Ruthenians as opposed to the delegates from the Supreme Ruthenian Council), but he deliberately ignored the Ruthenian issue in his speeches there.

Those who joined — both aristocrats and the aforementioned ex-conspirators — called themselves "Ruthenians of the Polish nation." But, considering their vision of the future, they were rather "Poles of Ruthenian descent." Almost all of them belonged to the National Council and participated in Polish political life. For example, Jan Zachariasiewicz, a Ruthenian Pole of Armenian descent, edited the radical democratic newspaper Postęp in Lviv in those months.

These "Polish" founders of the Congress were later joined by some Ruthenians from the National Council camp. Although they felt politically and culturally affiliated with the Ruthenian people, they saw the latter's development in close cooperation and alliance with the Polish people. Most of them were also representatives of the secular intelligentsia. Previously, they participated in Ruthenian cultural life, some playing a crucial role in it. Initially, some of them even joined the Supreme Ruthenian Council, but later disagreed with the policies of the conservative hierarchy that had suddenly appeared to be at the head of the Ruthenian political movement. Most importantly, however, they often did not see in the independent Ruthenian movement the power to give a proper response to the social challenges of the time and, accordingly, to ensure the full development of their people. In their view, Ruthenians could defend and deepen the constitutional freedoms won during the revolution only in alliance with Polish liberals.

The leading ideologue of this group is considered to be Kyrylo Wińkowski, an employee of the fiscal administration in Lviv, and a member of the Stauropegean Institute. Wińkowski was remembered for the fact that on March 19, the first day of demonstrations in Lviv, he was the first among the Ruthenians to declare their existence as a people on an equal footing with the Poles, thus becoming perhaps the first spokesman for Ruthenian "separatism." At first, in early May, he joined the Supreme Ruthenian Council but later proved to be a supporter of the Polish-Ruthenian agreement and signed the appeal of the Ruthenian Congress. He thus got expelled from the ranks of the Council. In the summer, he became the only member of the Congress to win a seat in the Austrian parliament. Another well-known future Ruthenian politician, Yulian Lavrivskyi, left the Supreme Ruthenian Council in June due to the disagreement with its policies and took part in the activities of the Congress as well. In October, however, he participated in the Congress of Ruthenian scholars organized by the Ruthenian Council (its liberal wing).

Perhaps the most famous Ruthenian among the Congress members was Ivan Vahylevych, a former member of the Ruthenian Triad, one of the founders of the Ruthenian cultural movement in Galicia in the 1830s. Even at that time, because of his activities, he and like-minded people were subjected to censorship and disciplinary repression from the upper circles of the Greek Catholic metropolitanate, so he was skeptical of their current political endeavors. At the time of the revolution, in the spring, Vahylevych, as a parish priest, stayed outside Lviv and was cut off from political activity, but in the summer he accepted the Congress' invitation to move to the city and to edit their newspaper.

However, not all Ruthenians having secular professions or liberal views joined the Congress. For example, Ivan Borysykevych, a lawyer, became deputy chairman of the Supreme Ruthenian Council and prepared its charter, while Antin Paventskyi, a Lviv notary, edited its newspaper, the Zoria Halytska. Both, together with priests like Mykola Ustyjanovych and Yakiv Holovatskyi, represented the liberal wing within the Supreme Ruthenian Council. Therefore, it was not so much the origin or social status that played the primary role in choosing the pro-Polish or pro-Ruthenian vector. It was rather the political or cultural landmarks, or the extent to which one or another person was involved in the Polish cause and culture.

In total, of the 64 signatories to the Congress's first appeal (it is the organization's fullest list of supporters), about half were secular intellectuals — officials, lawyers, or writers; nearly a quarter were landowners; only three of them were priests (with no Roman Catholic among them); and only six were students or seminarians. The clergy of both rites were apparently too restricted by corporate discipline to risk being at odds with the metropolitanate's general line — rather pro-Polish among Roman Catholics, clearly anti-Polish among Greek Catholics and rather pro-monarchical in both. One of those who took the risk — Fr. Onufriy Krynytskyi, who had been involved in the revolutionary movement from the first days, took part in a delegation to the emperor and joined the National Council, — received a severe reprimand from the church leaders with whom he had been in private conflict anyway. As for young people, they, apparently under the influence of revolutionary events, preferred to make an unequivocal national choice and had little interest in an organization that offered a kind of vague dual identity.

A separate category among the signatories of the appeal comprised the "citizens of the city of Lviv" ("Obyw. M. Lw."). Such a signature was used by people who did not specify any profession or employment, so the city became the only “affiliation” for them. But there were also some lawyers and officials among them too, such as O. Łodyński from the magistrate. Probably, they tried to emphasize their belonging to the city where it was not so easy to get and gain a foothold, moreover, in a respectable position. For example, of the 32 lawyers available in Lviv at the time, only six were listed as Ruthenians or Greek Catholics; it is quite indicative that four of them signed the Congress' appeal.

Both groups — Poles with Ruthenian roots and Ruthenians favoring the Polish movement — continued to form two wings within the Ruthenian Congress, which differed in their views on the national question. Representatives of the "Polish" wing were ready to sympathize with Ruthenian cultural needs but viewed them only as a certain ethnocultural component of a single Polish political nation. In this respect, they were close to the majority of the other members of the National Council (to which they themselves belonged). Rather, they needed the Ruthenian Congress in order to skilfully integrate Ruthenians into the Polish national project by satisfying their basic needs.

Representatives of the "Ruthenian" wing, on the other hand, clearly articulated the original identity of the Ruthenian people and their right to independent national development. They saw the Ruthenians not as a component subordinated to a single whole, but as an equal partner of the Poles in a common political life. In this aspect, they were much closer to the members of the Supreme Ruthenian Council than to the National Council but had a radically different vision of the Ruthenian political future. While the "Polish" wing hoped to build up a Polish national movement with the help of the Ruthenians, the "Ruthenian" wing hoped to give impetus and develop the Ruthenian nation itself with the help of the Polish movement.

The "Polish" wing of the Congress significantly outnumbered the "Ruthenian" one both quantitatively and in status and influence (particularly because it was represented by aristocrats). Instead, the views of the "Ruthenian" wing had more potential to find supporters among the Ruthenian population itself. Therefore, the official position expressed in the appeals and publications of the Congress was rather a compromise between the two visions, satisfying both parties and, at the same time, neither of them.

The National Question

The Congress treated the Supreme Ruthenian Council accordingly. Its representatives never openly opposed their opponents by word of mouth, calling for cooperation instead. Both organizations, they insisted, could complement each other organically. They held that the Supreme Ruthenian Council, being an institution composed mainly of clergy, could continue to take care of the moral and spiritual needs of the people. And the Ruthenian Congress as a secular institution could take over its political representation.

Antoni Dąbczański, an adviser to the Nobility Court in Lviv, went as far as to address the Supreme Council on May 29 with a proposal to unite on behalf of the Congress. He argued that although the Council had a greater influence on the common people, whom it sought to enlighten, it would not be able to achieve its goals without the support of the secular intelligentsia and aristocracy. Later, the chairman of the Council, Bishop Hryhoriy Yakhymovych, wrote to Metropolitan Mykhailo Levytskyi that the representatives of the Congress had been ready to make significant concessions for the sake of merging or even joining the ranks of the Council. The latter, however, refused as the two organizations had declared different political goals in their appeals. Yakhymovych wrote that the union "would not help them in any way, and it would be detrimental to us because of the trust placed in us" (it is unknown, however, what kind of trust the bishop meant, that from the people or that from the government).

Probably one of the concessions discussed was the possible transition (or return) of the aristocracy of Ruthenian descent to the Byzantine rite. According to the memoirs of one of the known figures of that time, Stepan Kachala, some Ruthenian aristocrats, led by Volodymyr Didushytskyi, turned to Bishop Yakhymovych with a proposal for cooperation and a request to take them back to the Byzantine rite. The bishop allegedly replied that the Ruthenians "had no nobility and did not need it." This episode has not been confirmed by other sources, but it became the most famous and striking example of negotiations between the two competing Ruthenian representations in mid-1848 nevertheless. If the episode was real, the answer could have shown that the Greek Catholic leaders were in fact driven not so much by the care for their rite as by their unwillingness to share their defining influence in the movement they led and by the reluctance to undermine the chosen political course of being loyal to the government and opposed to the Polish movement.

The aristocrats rejected by the bishop found a way to show their "Ruthenianness" within the Congress. Representatives of the Congress declared in the charter the supra-denominational character of the Ruthenian people and defended its social wholeness in their publications. The Ruthenian people, in their opinion, should consist of all social classes — nobility, intelligentsia, clergy, bourgeoisie, and peasantry, — that is, of all who had Ruthenian roots or wanted to belong to the Ruthenians. The criterion of "Ruthenianness", respectively, was not a rite or religion but the origin and conscious choice.

Representatives of the Congress confirmed their model with historical arguments. They acknowledged that, at the beginning of their history, the Ruthenians were an independent people with their own powerful statehood. However, their state perished under the blow of the Mongols, and it was only in alliance with the Poles that the political life of the Ruthenians gained new meaning. Together, the Poles and the Ruthenians defended themselves and Europe from nomadic attacks, becoming the West's barrier in front of the wild East. A special role in this story was given to the "Ruthenian knights" — the Cossacks. Although the nobility accepted another rite, they never ceased to be Ruthenian and now sought to restore ties and trust with their people. According to the position of the National Council, it was the gentry who was presented as the main initiator of the serfdom abolition, while all the troubles of the common people were associated with the policy of the bureaucracy.

In current politics, the representatives of the Congress also paid considerable attention to the Dnieper Ukraine: the Ruthenians from Galicia and Ukraine were to form a liberal federal alliance with the Poles against the conservative regimes of Austria and Russia. Revolutionary Galicia, centered in Lviv and Krakow, was to be the germ of the restoration of independent and allied Ruthenia and Poland, respectively. The main propagandist of those ideas was Henryk Jabłoński, a young poet and publicist, one of those representatives of the Congress, who was born on the other side of the Austro-Ruthenian border but moved to Lviv, studied at the university there and actively published his writings.

Conclusions

First of all, the Congress did not build up a clear internal structure (or at least did not leave any evidence of this). There is no evidence of any meeting of the organization taking place later than early June, no evidence of the election of some management and the formation of committees or local branches. The fact that such activities were not provided for even in the charter may indicate that the founders of the Congress did not have clear intentions to build it up from the very beginning. The main arena of their political activity was the National Council, and they perceived the Congress rather as a tactical tool to subordinate the newly born Ruthenian movement to the interests of the Polish movement. However, it was more or less successful only at the Slavic Congress in Prague, where, thanks to the larger representation of the "Ruthenians of the Polish nation" — Leon Sapieha, Julian Dzieduszycki, Kasper Cięglewicz, Jan Dobrzański and others, — they managed to speak on behalf of the Ruthenian people on a par with the delegates sent by the Supreme Ruthenian Council.

In the domestic arena, however, these efforts were unsuccessful. It is here that the second problem of the Congress became apparent: the main idea it promoted — the Polish-Ruthenian dual identity and an alliance with the Polish movement — had a very limited social base. The two main social groups on which the Congress relied — the nobility and the secular intelligentsia — were not numerous among the Ruthenians, and those aristocrats or intellectuals who had an unambiguous Polish identity did not need a Ruthenian "appendix." Instead, the two most numerous categories of Ruthenians — priests, who were restricted by corporate discipline, and peasants, who were negative about everything that was "Polish" and therefore "lordly", — came under the influence of the Supreme Ruthenian Council.

In the absence of a developed structure, the Congress did not have a bright leader who would lead the "Ruthenians of the Polish nation" after him. The leadership was rather situational in nature and depended on the initiative shown at a particular moment and the ability to address pressing issues. The first chairman, Kasper Cięglewicz, was elected at the first meeting on May 23. However, he was removed after two weeks of presidency (hence, apparently, the norm of the chairman election every two weeks), when there was a need to more clearly declare their commitment to the Ruthenian cause and to seek compromises with the Supreme Ruthenian Council. At that time, Antoni Dąbczański, an adviser to the Nobility Court in Lviv, who was responsible for negotiations with the Council, took over the leadership for a while. Instead, in October, as the Congress became increasingly close to the Polish National Council, it was already led by Antoni Golejewski, a landowner, who represented the Congress in the National Council for a long time and was responsible for the "Polish" vector.

Until the very end of its existence, the Congress — and this is its third major problem — remained divided into two camps. In early October, when the large pro-Polish wing was already negotiating a full merger with the National Council, the pro-Ruthenian "opposition" greeted participants in the Congress of Ruthenian scholars on behalf of the Congress.

Thus, without building up an internal structure, without gaining wider public support and without a single center of gravity, the Congress remained a group of people from different backgrounds, often driven by different motivations and united only by a common answer to a pressing problem that suddenly arose. Without any specific political activity, its existence gradually lost its meaning. As a result, the Ruthenian Congress became the only one of the four political organizations that emerged in Lviv during the Spring of Nations, which did not survive till the uprising of November 1 and as early as October 6 voluntarily joined another organization, the Central National Council.

Nevertheless, despite the "defeat" of the idea of a Polish-Ruthenian union and the rather archaic nature of the dual identity, some ideas of the Ruthenian Congress — in particular, the idea of a non-denominational character and social wholeness of the people and the need for secular leadership in the national movement — corresponded to the modern understanding much more than the position of the Supreme Ruthenian Council. Some of these ideas were later adopted by the populist movement, which unfolded in Lviv in the 1860s and initiated a new stage in the Ruthenian national movement, directing it to Ukrainophile positions. One of the leaders of this movement was Yulian Lavrivskyi, who in 1848 maneuvered between the two Ruthenian camps.

The concept of gente Rutheni, natione Poloni, which became one of the cornerstones of the Ruthenian Congress, continued to function among Poles of Ruthenian descent, aristocrats and secular intellectuals in particular, throughout the 19th century. Later one of its most famous followers was Prince Adam Sapieha, son of Leon. However, politically it completely merged into the Polish national movement, and it was within the framework of the latter that it was gradually marginalized until it finally disappeared at the turn of the 20th century.

Related Stories

Related Places

Vul. Lesi Ukrainky, 01 – Maria Zankovetska Theater (former Skarbek Theater)

Show full description

Kulczycki's House - Ferdinand sq.

Personalities

Kasper Cięglewicz — a former Polish conspirator, the first chairman of the Ruthenian Congress

Kyrylo Vinkovskyi (Wińkowski) — an official of the fiscal administration in Lviv, first a member of the Supreme Ruthenian Council, later the leader of the "Ruthenian" wing in the Ruthenian Congress

Ivan Vahylevych — a poet and scientist, the editor of the newspaper Dnewnyk Ruskij published by the Ruthenian Congress

Yulian Lavrivskyi — a lawyer, first a member of the Supreme Ruthenian Council, later a supporter of the Ruthenian Congress, a participant in the Congress of Ruthenian Scholars

Leon Sapieha, prince — a member of the Central National Council and the Ruthenian Congress

Włodzimierz Dzieduszycki (Volodymyr Didushytskyi), count — a member of the Central National Council and the Ruthenian Congress

Antoni Dąbczański — an adviser to the Nobility Court in Lviv, a member of the Central National Council, one of the leaders of the Ruthenian Congress, a negotiator on the latter's behalf with the Supreme Ruthenian Council

Antoni Golejewski — a landowner, a member of the Central National Council and the Ruthenian Congress, an initiator of the latter's merger with the Council

Julian Horoszkiewicz — a poet, a former Polish conspirator, Leon Sapieha's secretary, a member of the Central National Council and the Ruthenian Congress

Michał Popiel — a landowner, a former Polish conspirator, a member of the Central National Council and the Ruthenian Congress

Jan Zachariasiewicz — a Pole of Armenian descent, a former Polish conspirator, a member of the Ruthenian Congress, the editor of the Postęp newspaper

Organizations

Sources

- Мар'ян Мудрий, "Руський Собор 1848 року: організація та члени", Україна: культурна спадщина, національна свідомість, державність, №16, 2018, 107–126;

- Мар'ян Мудрий, "Русини польської нації" (gente Rutheni, natione Poloni) в Галичині XIX ст. і поняття "вітчизни", Україна: культурна спадщина, національна свідомість, державність, №15, 2016–2017, 461–474;

- Jan Kozik, The Ukrainian National Movement in Galicia: 1815–1849, (Edmonton: Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, 1986);

- John-Paul Himka, "The Construction of Nationality in Galician Rus': Icarian Flights in Almost All Directions," Intellectuals and the Articulation of the Nation, Edited by Ronald Grigor Suny and Michael D. Kennedy, (The University of Michigan Press, 1999), 109–164;

- Andriy Zayarnyuk, "Obtaining History: The Case of Ukrainians in Habsburg Galicia, 1848-1900," Austrian History Yearbook 36, 2005, 121–147

- Dnewnyk Ruskij, 1848, №1–9.