To effectively manage the Jewish population of Lviv and to prepare for its forced isolation in the ghetto, the Nazis created a Provisional Board of the Jewish Religious Community, or the Jewish Council (Judenrat).

On July 22, 1941, a relevant resolution of the Lviv City Administration was issued, signed by its chairman Yuriy Poliansky. It was published in the 15th issue of the Ukrainski Shchodenni Visti as follows:

RESOLUTION of the Lviv City Administration, 22 July 1941

§ 1.

To organize the Jewish community of Lviv.

§ 2.

To approve the Provisional Administration of the Jewish religious community as follows:

Chairman: Dr. Josef Parnas, a lawyer residing at vul. Pekarska 1c.

Deputy Chairman: Dr. Adolf Rotfeld, a lawyer residing at vul. Panska 2.

Administration members: Dr. Isidor Ginsberg, a doctor residing at vul. Yagellonska 15; Jozua Ehrlich, a merchant residing at vul. Ofitserska 14; Isak Seidenfrau, a merchant residing at pl. Krakivska 2; Jakov Hirer, an artisan residing at vul. Riznytska 3; Naftali Landau, an engineer residing at vul. Asnika 11.

§ 3.

The house at vul. Starotandetna 2a, which was originally intended for a new clinic, to be assigned for the needs of the Jewish religious community.

At the same time, to oblige the Lviv Health Department and the Housing Department to find another suitable building for the Jewish polyclinic.

§ 4.

To allow the Jewish community to impose a tax on community members for the purposes of the community organization and funding of its institutions.

§ 5.

To establish the following temporary range of the Jewish community’s activities:

1) Keeping registers of births. 2) Keeping records of the Jewish population. 3) Maintaining hospitals, clinics and sanitary facilities for the needs of the Jewish population. 4) Organizing social security, cheap kitchens and provision.

Chairman of the City Administration of Lviv: Dr. Y. Poliansky

The Provisional Administration was to ensure the unimpeded execution of Nazi orders concerning all spheres of Lviv Jews’ life.

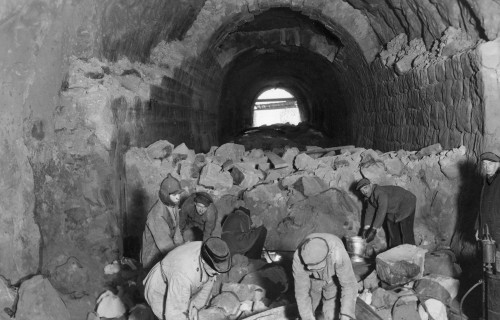

At first, the Jewish Homeless Asylum building was used to provide the work of the Judenrat administration. Nowadays, in modern Lviv, it is a well-known public center — the First Media Library. Built over three years in the interwar period by the Jewish Society, the homeless asylum could simultaneously shelter 134 needy people (52 men, 52 women, and 30 mothers with infants) and feed up to 1,500 people a day in the charity kitchen. However, in less than ten years, the building became a center that governed the lives of all Jews in Lviv.

The Judenrat regulated the life of the Jewish community. On the orders of the Nazis, it assigned able-bodied men for forced labour (the so-called labour exchange), collected taxes, maintained social institutions (clinics, hospitals, nursing homes), managed industry and trade in the ghetto, provided the population with food and housing and, with the help of the Jewish Order Service, maintained order in the ghetto.

The Judenrat structure included the following subdivisions: the personnel department, the housing department, the economic department, the labour department, the tax department, the social department, the health care and sanitation department, the legal department, the construction department, the education department, the religion department, and the funeral department.

Now, mentioning the Judenrat, we usually think of only those people who headed the subdivisions or the institution itself; however, it was quite large in number of employees: while at first there were up to a thousand employees in the Judenrat, in 1942 there were five thousand of them.

The first Judenrat in Lviv was proposed to be headed by Dr. Maurycy Allerhand, a lawyer and professor at Lviv University who had headed the Jewish community before the war. However, he refused, pleading his age and poor health. Then the authorities appointed the council independently, and Josef Parnas became the chairman. A well-known lawyer in Lviv, he was already 70 years old at that time. It is known that he was executed for refusing to follow a direct order from the security police and the SD regarding the deportation of 500 able-bodied men to a labour camp.

After Josef Parnas, this position was taken over by his deputy, Dr. Adolf Rotfeld. He was a lawyer by education, but worked as a journalist, and before the war it was he who led the Zionist movement. Adolf Rotfeld was the only leader of the Judenrat who was lucky enough to die a natural death. Everyone else was killed. Under Rotfeld, the Judenrat members began to openly abuse their positions. The community hoped that the chairman would put an end to this, but it did not happen. The rule of this chairman was marked by the fulfilment of all the demands of the Nazis.

In March 1942, the Judenrat was headed by Dr. Henryk Landsberg, a lawyer, public figure, and activist of the Bnei Brit organization. He also did not try to openly oppose the orders of the Nazis and did what was required of him. Rabbi David Kahane describes the meeting of the Lviv Council of Rabbis consisting of Rebbe Israel Wolfsberg, Rebbe Mosze Elhanan Alter, Rebbe Dr. Kalman Hameides and Rebbe David Kahane himself with Dr. Henrik Landsberg. The Council of Rabbis tried to prevent the Judenrat chairman from transferring Jews to labour camps in accordance with Nazi orders:

…It is better for everyone to die, but not to give any Jew to the enemy. This is what the principles of the Halakha say.

We saw that the words touched an open wound. His [Dr. Landsberg’s — ed.] face took on a fierce expression, and he exclaimed, "It seems to you, gentlemen, that you are still living in the pre-war times and that you have come to the head of the religious Kahal. Let me inform you that times have changed completely. We are no longer a religious community, but a tool for carrying out Gestapo [security police — ed.] orders..."

The last chairman of the Judenrat was Dr. Edward Eberzon. According to memoirs, he was a decent but weak-willed man. He headed the council until its liquidation, when he and the other members were killed.

In the memoirs of Krystyna Chiger, who survived the Holocaust in Lviv as a 6-year-old girl, we find an assessment of the Judenrat:

…the Judenrat, the Jewish Council, became a kind of aid organization for the Jewish community. The Judenraete worked all over Poland [under the Nazi occupation — ed.]. These were organizations created by the Jews for the Jews. On the one hand, they provided help, support and communication between the Jews; on the other hand, they became a kind of bridge between the Nazi government and the ghetto population. The Germans supported the Judenraete because they allowed them to address and guide the Jews directly. My father always pointed out the irony of fate: an organization created to help oppressed and persecuted people was used to make it easier to oppress and persecute the people it was to serve. The Judenraete were a hand outstretched to the drowning man, but able to push him back into the water at any moment. However, in some matters, such as finding housing, looking for relatives or Jewish acquaintances, the Judenrat was very helpful…

Simultaneously with the formation of the Judenrat, the Nazis were preparing other structures in the chain of control, exploitation and destruction of the Jewish community. Thus, from August 1941, able-bodied Jews had to register with the Labour Exchange and to be engaged in forced labour; besides, from November 1941, all Jews in Lviv had to move to a separate area of compact residence — a ghetto in the northern part of the city, behind the railway.

Until August 1942, the Judenrat was located on vul. Muliarska. However, when half of Lviv's Jews were killed, it was transferred directly to the ghetto, first to a house on vul. Kushevycha, which once belonged to the tram depot workers, and later to the house located at the corner of ul. Jakuba Hermana 15 (now vul. Lemkivska) and ul. Loketka 5 (now vul. Ivana Trusha). On January 5, 1943, when the ghetto was transformed into the Julag (Judenlager), the Judenrat was closed and its workers were killed.

Modern historians question whether the Judenrat workers were collaborators and aides to the Nazi administration or hostages of the situation. There is no hope of finding an unambiguous answer to this question: most members of the Judenrat were appointed by the occupying regime, which changed the composition of the institution, usually after the execution of its previous members. In any case, however, leading a Judenrat meant following the orders of the Nazis.