Ivan Franko Park (formerly, Jesuit Gardens) ID: 21

Ivan Franko Park occupies the property located on a hillside of the Lviv Heights between Lystopadovoho Chynu and Krushelnytskoi Streets. The land was once part of an outlying monastic (Jesuit) grange, from which the name Jesuit Gardens is derived. Toward the close of the 18th century, Emperor Joseph II granted the land to Lviv townsfolk for the establishment of a municipal park. In 1855, the territory was redesigned by town horticulturist Karl Bauer as a landscaped park. The arboreal landscaping boasts a variety of species of varying ages including maples, oaks, linden, chestnut, and others.

Story

Lviv’s first municipal park occupies land which in the 16th century belonged to the patrician Szolc-Wolfowicz family and the Venetian Consul, Antonio Massari. From here it passed into the possession of the Jesuit Order which maintained the property until the time of Emperor Joseph II, and from which it derives its name Jesuit Gardens.

Ivan Krypyakevych provides the following description of its early history: “the Jesuits established a brickworks, followed by a brewery, an inn, and settled peasants on the land, creating a full-fledged grange. It survived a series of military-related incidents. In 1655, during Bohdan Khmelnytskyi’s siege of Lviv, the Moscow artillery occupied the land, stationing a gun battery and built up ramparts. In 1672, the Turkish troops were here” (Krypyakevych, 1991, 121).

After the attachment of Galicia to the House of Habsburg, Emperor Joseph II, in an application of his policy of suppression of monasteries and confiscation of monastic holdings, gifted the land to the city. In the words of Zigmund Stankiewicz: “Emperor Joseph II took pains to gift the residents of Lviv a garden that the Jesuits had once striven to outfit – after the style of the times – in all the refined elegance of the Italian manner” (Stankiewicz, 1928, 63). (It is evident that this is the same line of thought the Emperor followed in granting public access to the Imperial Gardens in Vienna).

Due to the neglect of proper maintenance however, the condition of the newly created municipal park quickly deteriorated, and in 1799 city authorities were compelled to grant a lease of the park in perpetuity to restaurateur Johann Höcht. For his part, Höcht was obligated to maintain the park in accordance with the needs of the community. Höcht “arranged things in the French manner, with bathing areas, groves, open-air theater performances in summer, bonfires, carousels…in the place where the Council building now stands, he erected a two-story structure well-known under the name of the “Höcht Casino”, where he held performances, balls, masquerades and also signed contracts” (Janusz, 1922, 54-55).

During the first half of the 19th century, poor drainage of the lower terrace of Jesuit Gardens resulted in a situation where rainwater runoff from the hill of St. Mary Magdalene Church began to pool, gradually turning the area into a swamp. (“The water had nowhere to go…turning the place into a quagmire, flooding the carousel, ruining it, and turning the lawns into stands of horsetails and marsh grass.”)

The Höcht family attempted to rectify the situation while maintaining their private business interests as well as the public interest (Stankiewicz, 1928, 65), yet in time the Gardens again fell into disrepair, and more respectable elements of the public began to avoid the area. It was at this time that further complications of a legal character arose – concerning ownership of the park. These would be decided only through the intervention of a state-appointed arbitrator. Thanks to the efforts of the Galician Eparchy, an agreement was reached with the property’s final private title-holder, Franciszek Wędrychowski, providing for the reacquisition of the property by the city. “An attentive government, addressing fundamental matters…took the needs of the city upon itself, ensuring adequate space for walking, for social gatherings…for maintenance of the public health” (Stankiewicz, 1928, 63, 66). Following the turbulent events of 1848, local authorities were desperate for public goodwill, and from this sprang the initiative to reconstruct the Jesuit Gardens that it serve as a city park – a worthy place for the middle class to spend their leisure hours.

On April 12, 1855, the renovation project proposed by Karl Bauer – the director of Lviv Municipal Gardens – was approved. Bauer’s overall landscape design for the former Jesuit Gardens – now Ivan Franko Park – has been maintained to the present day.

In 1881 the park’s lower terraces, adjacent to the recently constructed neo-renaissance home of the Galician Council, were re-landscaped. According to Krypyakevych, “in 1886 a lane extending from the current Tretyoho Maya Street (presently, Sichovykh Striltsiv) was destroyed; it was re-established in 1925…a violent storm leveled the park during the 1890s. Hundreds of mature trees were felled and lay in mass that made it impossible to pass through” (Krypyakevych, 1991, 122).

Sometime after 1919, Jesuit Gardens were renamed Tadeusz Kościuszko Park, and after 1945, Ivan Franko Park. Reconstruction of the park was undertaken in 2009. Today, Lviv’s Ivan Franko Park enjoys the status of the longest standing municipal park in Ukraine.

Architecture

The municipal park known as Ivan Franko Park was established on the territory of an old Jesuit Order grange located in the southwestern, and previously outlying, section of the city. It occupies a trapezoid on a gentle hillside of the Lviv Heights.

The establishment of the Jesuit Gardens as a municipal park set in motion the creation of the second ring – following that of the lane and the walks on “the heights” – of parklands in Lviv’s “Emerald Gown” system, to invoke Zygmunt Stankiewicz’s delightful phrase (Stankiewicz, 1928, 63). This outer ring would eventually include Vysoky Zamok Park and abut the Znesinnya parcel of land, the Tsetnerivky green zone, the Lychakiv Cemetery and Walks (Pohulyanky), Stryiskyi Park and other tracts of green space which encircled the town’s historical center in the Poltva dale.

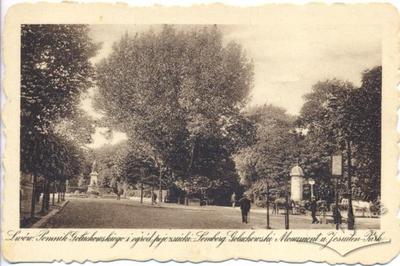

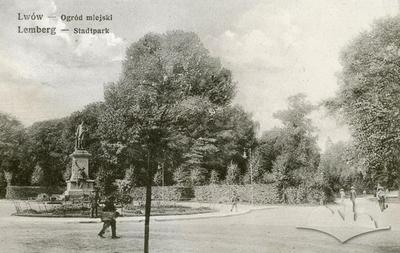

Near the close of the 19th century, Michal Kowalczuk published the following account: “The municipal gardens, known also as the Jesuit Gardens…is the closest to the city center. It fills a parallelogram between Marshalkovska, Mitskevych, Mateyko and Krashevsky Streets (presently, Universitetska, Lystopadovoho Chynu, Mateyko, and Krushelnytskoi) (Miasto Lwów, 1896, 318).

Lviv’s oldest municipal park enjoys a varied, and striking, layout. On its northern edge it adjoins the central building of Lviv University, the former Galician Council building. Near its southern, elevated side, sits the historical campus of Lviv Polytechnic. On the western side, on Lystopadovoho Chynu Street, the former residence of the Galician Eparchy (currently the Railroad Hospital campus) is located within park grounds. On the east, along the odd-numbered side of Krushelnytskoi Street we may observe a housing complex embodying one of the finest examples of Historicist architecture in Lviv. The St. George Cathedral dominates the southwestern corner of the park.

The massive railroad administrative center, built at the base of St. George’s Hill at the start of the 1910s, strikes a dissonant note in this otherwise elegant architectural ensemble. Even greater disruption is brought by the prismatic, multi-storied block of the Hotel Dniester. Erected in the 1970s, the hotel stands over the park, an alien presence in the neighborhood’s architectural panorama.

Over the park’s more than three-century-long existence its layout has undergone repeated readjustments. Ivan Krypyakevych writes that by the end of the 16th century, “the tradesman Johannn Szolc-Wolfowicz expended 1,600 gold pieces on the garden. From there it passed into the hands of his son-in-law Antonio Massari, an Italian originally from Venice, and he designed a park after the Italian manner”. Johann Höcht subsequently reformulated the park “in the French manner” (Krypyakevych, 1991, 122), and from that time we observe a consistent, geometric, “French” structure to park lanes, as attested on Lviv maps dating from the first half of the 19th century. Karl Bauer’s original plan for the territory was for an asymmetrical landscaped park. Lviv’s Jesuit Gardens have conformed to Bauer’s basic 1855 configuration and layout now for more than a century and a half.

Sometime later, structured flower beds in a style characteristic of baroque-era horticulture were laid in on the lower terraces near the Galician Eparchate. This floral accent stands out as it repeats along the park’s central lane. The lane, reestablished in the 1920s, runs straight uphill the length of the territory, parallel to Krushelnytskoi and Lystopadovoho Chynu streets. It runs along the park’s eastern edge with spacious, winding paths branching off it. In search of relaxation, one may select the lively and popular “main throroughfare” or a cozy spot in the heart of the park, removed from the crowd. The park also has a children’s play area.

Of the buildings in Ivan Franko dating from the first half of the 19th century, there is a rotunda with Doric colonnade typical of park structures from the Romantic era. At the entrance of the central lane stands a Classical iron vase with relief influenced by the work of Bertel Thorvaldsen.

In 1964, the Ivan Franko monument (sculptors, Valentyn Borysenko, Dmytro Krvavych, Emmanuil Mysko, Vasyl Odrekhivskyi, and Yakiv Chaika; architect Andryi Shulyar) was raised in the park opposite the Academic Center of Lviv University. Flowerbeds were removed to make room for the sculpture, breaking the compositional line – as noted by Tetyana Maksymiuk – which both visually and functionally, linked the university campus with the lower entrance to the park (Lviv Architecture, 2008, 637).

According to Michal Kovalchuk, in the 1890s the Jesuit Gardens encompassed 10.17 hectares where grew "ironwood, elm, linden, larch, arborvitae, spruce and fir, black elderberries, hawthorn, and hazelnuts…" (Miasto Lwów, 1896, 318-319).

Olena Stepaniv imparts the following information gleaned from the early 1940s: “The soil in the park is a mixture of clay, sand, and humus. The formerly boggy lower gardens were filled in and drained. Oaks, maples, poplar, ironwood, linden, elm, fir, larch, and even a few Pryvyslianskyi poplar. Park vegetation suffered a great deal of damage in the war (1939-1941)” (Stepaniv, 1992, 46).

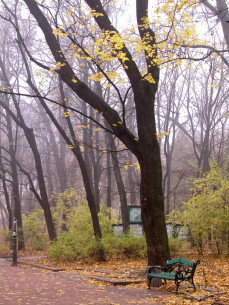

Of the trees in Ivan Franko Park, the maples lining the central lane, the old oaks in the upper reaches of the park, and the ashes near the Doric Rotunda are certainly impressive (Lviv Architecture, 2008, 638). The park has both old and new growth trees, with its primary stand comprised of plantings dating from the mid to late-19th century. In addition to native European flora, exotic specimens from South America, the Far East, and the Mediterranean region have been planted in the park.

As of today, the park occupies 11.6 hectares.

Related buildings and spaces

People

Karl Bauer. Landscape architect, park

designer.

Valentyn Borysenko. Sculptor.

Franciszek Wędrychowski. Park owner.

Johannn Höcht. Park owner.

Joseph II. Holy Roman Emperor of the Habsburg

Dynasty.

Michal Kowalczuk. Architect, critic, guidebook

author.

Dmytro Krvavych. Sculptor.

Ivan Krypyakevych. Historian.

Tetyana Maskymiuk. Architectural Historian.

Antonio Massari. Venetian Consul, property owner.

Emmanuil Mysko. Sculptor.

Vasyl Odrekhivskyi. Sculptor.

Zygmunt Stankiewicz. Engineer, ethographer.

Olena Stepaniv. Historian, geographer, civic

activist.

Bertel Thorvaldsen. Sculptor.

Bohdan Khmelnytskyi. Cossack Hetman.

Yakiv Chaika. Sculptor.

Scholz-Wolfowitz. Bourgeois, merchant family,

landowners.

Andryi Shulyar. Architect.

Organizations

Sources

- Biriulyov, Yuryi, ed. Architecture of Lviv: Times and Styles, 13th-21st centuries. Lviv: Center of Europe Publishing, 2008. Print.

- Krypyakevych, Ivan. Historical Walks Around Lviv. Lviv: Kamenyar, 1991. Print.

- Stepaniv, Olena. Contemporary Lviv: A Guidebook. Lviv: Phoenix, 1992. Print.

- Barański F. Przewodnik po Lwowie: Z planem i widokami Lwowa (Lwów, [1902]).

- Janusz B. Przewodnik po Lwowie: (Z planem miasta) (Lwów, 1922).

- Jaworski F. Lwόw stary i wczorajszy (szkice i opowiadania): Z ilustracyami. Wydanie drugie poprawione (Lwów, 1911).

- Miasto Lwów w okresie samorządu 1870–1895 (Lwów, 1896).

- Orłowicz M. Ilustrowany przewodnik po Lwowie: Ze 102 ilustracjami i planem miasta. Wydanie drugie rozszerzone (Lwów – Warszawa: Książnica-Atlas, 1925).

- Stankiewicz Z. Ogrody i plantacje miejskie // Lwów dawny i dzisiejszy: Praca zbiorowa pod redakcja B. Janusza (Lwów, 1928), 62–71.

Urban Media Archive Materials