Rudolf Weigl’s Institute ID: 207

The Typhus Research Institute led by Rudolf Weigl became a place of rescue for many memebers of Lviv intelligentsia, including Jews. The story is a part of the theme Reactions of Lvivians to Holocaust, which was prepared within the program The Complicated Pages of Common History: Telling About World War II in Lviv.

Story

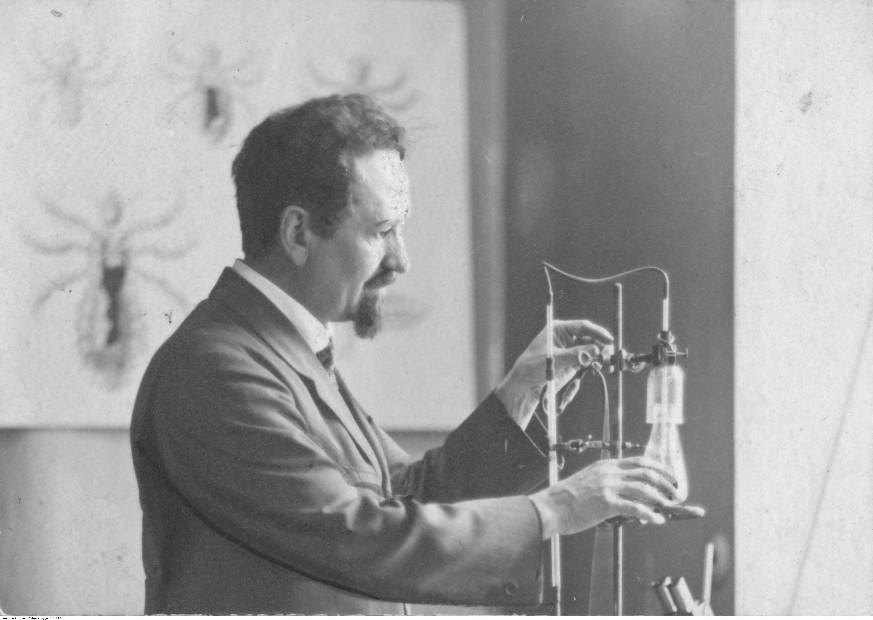

Rudolf Stefan Weigl (1883–1957) was a prominent physician, biologist, and immunologist known for inventing a vaccine against epidemic typhus. Due to the significance and recognition of his scientific achievements, Weigl became a professor and head of the Department of General Biology at Lviv University in 1920. The Typhus Research Institute, known as Weigl’s Institute, was established within this department. Both during the Soviet occupation of Lviv and after the arrival of German troops, Professor Weigl remained the head of this institute. The scientist retained his position because the vaccine he had developed was intended for military use. Initially, the Institute was located at the Faculty of Biology of the Jan Kazimierz University (ul. Św. Mikołaja, now vul. Hrushevskoho). During the war, the institute was provided with an additional large building — the premises of the former women's gymnasium (now the Institute of Blood Pathology of the Academy of Sciences of Ukraine at vul. Henerala Chuprynky 45).

The professor soon realized that the identification card of an employee of his Institute could basically protect one from a sudden arrest, as the Gestapo avoided contact with people potentially infected with typhus. This disease occupied a special place in the Nazi racial ideology as it was believed that typhus, transmitted by lice, was characteristic of "parasitic inhumans." Nazi propaganda often portrayed Jews as carriers of typhus. Professor Weigl began hiring people who were in particular danger, most notably members of the resistance movement and left-wing intellectuals. The certificate of his institute employee could save from persecution or forced deportation to the Third Reich. The technology of vaccine production required cultivation of the desease carriers in large quantities. They needed to be fed on humans. For this purpose, special bracelets with a membrane were created, which were worn on the arm or on the leg of "lice feeders." There was a huge staff of vaccinated "donors" who fed these insects. In addition to the certificate, the employees of the institute also received some food aid, which was very valuable in the conditions of wartime food shortages. According to various estimates, Weigl saved about 5,000 people (including Jewish scientists such as Ludwik Fleck and the Maisls). The vaccine, produced at the Institute, was smuggled to the Lviv and Warsaw ghettos, concentration camps and Gestapo prisons. Thus, Zbigniew Stuchły, an employee of the Weigl Institute, recalled as follows:

At

the initial stage of the Lviv ghetto creation, Weigl commissioned me to give a

lecture for Jewish doctors on the typhus vaccine there. In addition, as long as

it was possible, he kept in touch through me with Dr. Adam Finkel, our

researcher, who was locked up in the ghetto and then in the camp on ul. Janowska.

(Zbigniew

Stuchły, Wspomnienia o Rudolfie Weiglu, 1959)

Related buildings and spaces

Sources

- Arthur Allen, Fantastic Laboratory of Dr. Weigl: How Two Brave Scientists Battled Typhus and Sabotaged the Nazis, Norton 2014;

- Ludwik Fleck, Investigation of epidemic typhus in the Ghetto of Lwów in 1941–1942 (режим доступу 08.11.2018);

- Profesor Rudolf Stefan Weigl: Artykuły, Wspomnienia, Fotografie/ lwow.eu (режим доступу 08.11.2018);

- Zbigniew Stuchly, Wspomnienia o Rudolfie Weiglu, 1959.