To take Lviv with them: the resettlement and cultural heritage ID: 260

The story is a part of the theme The Epoligue of the War, prepared within the program The Complicated Pages of Common History: Telling About World War II in Lviv.

Story

The issue of the evacuation of cultural and artistic valuables arose for the staff of Lviv museums, archives and libraries as early as the autumn of 1943. Due to the front line approaching, there was a threat of destruction due to active hostilities. The most valuable parts of the collections of the Ossolineum, the Baworowski Library, the University Library, the City Archives, the Historical Museum and the Art Gallery were transferred inland, to "mainland" Poland. Since the evacuation of these collections took place under the supervision of the Nazi administration, the important task was to prevent their relocation to the Third Reich. In addition, measures were taken to preserve the remaining collections in Lviv. For example, the Ossolineum directorate moved part of the collection (manuscripts and ancient engravings) to the dungeons of the Dominican church. In April and May 1944, Soviet air strikes caused significant damage to the Wroclaw panorama, the buildings of the Ossolineum and the University Library, but the collections of these institutions were not damaged.

The 1944 Lublin Agreement did not mention the issue of the relocation of Polish cultural heritage, and until the spring of 1946 it was not a priority. After the war, thanks to the efforts of the Polish authorities, some of Lviv's works of art and collections were transferred to Poland. Thus, the Provisional Government of National Unity placed the Wroclaw Panorama in Wroclaw, where it was transported in 1946. The following year, 30% of the Ossolineum's funds (217,000 units) were transported by two trains to Poland (at the same time, more than 10,000 books were transferred to the Library of the Soviet Academy of Sciences in Moscow). Some of the Polish workers of the Ossolineum (led by the director Mieczysław Gembarowicz) did not move to Poland and remained to work in the Lviv branch of the Library of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR.

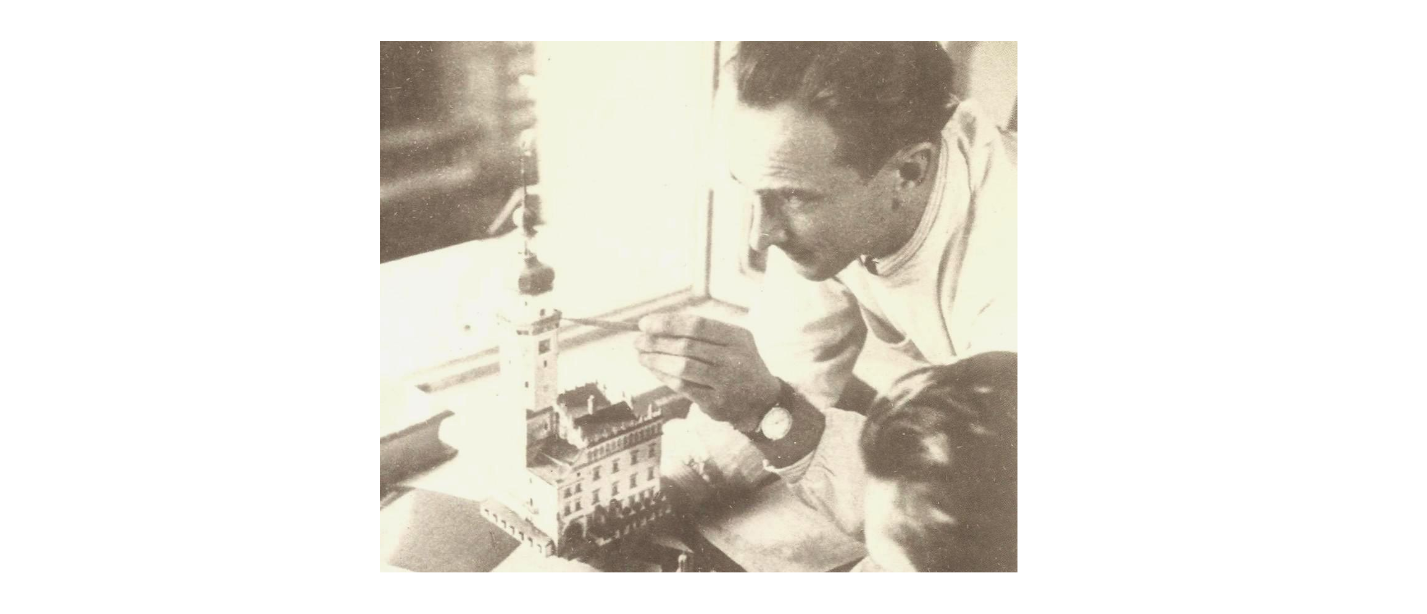

The fate of Janusz Witwicki, a Polish engineer and historian of architecture, and his model of 18th-century Lviv illustrate the complex relationship between the Soviet regime and Polish cultural heritage in postwar Lviv.

Witwicki began to work on an ambitious city panorama of Lviv at Lviv Polytechnic in 1932. In 1936, efforts were made to purchase a new two-room workshop in a building belonging to the City Council and located at ul. Ormiańska 23 (now vul. Virmenska, the so-called "Seasons" building). It was then that his work began on the construction of a model of Lviv on a scale of 1:200. Probably, the impetus for the creation of the Panorama was a collection of 17th-18th c. urban fortifications models he saw in Paris. The Panorama was partially financed by the City Council. To assist in its construction, the "Society for the Construction of the Model of Ancient Lviv" (Towarzystwo Budowy Panoramy Plastycznej Dawnego Lwowa) was established in December 1935. A team of designers and architects worked on numerous models of houses, churches, towers and fortifications. Witwicki made the most complex elements himself.

The panorama reflected the appearance of Lviv's buildings within the city fortifications as of 1772, on the eve of Lviv becoming part of the Austrian Empire. The plastic model reproduced the baroque pre-Habsburg architecture of Lviv, emphasizing the city’s Polish character. The grand opening of the Panorama was planned in 1949, for the 600th anniversary of Lviv's accession to the Kingdom of Poland. However, history made a different turn, and the model was never completed.The Soviet authorities did not want to lose this monument and made a lot of efforts to preserve it in Lviv. In 1944, Nikita Khrushchev, the then secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Ukrainian SSR, visited Witwicki's workshop, assessing his work as "very important" and promising support. A few months later, the Lviv regional committee of the communist party recommended continuing the Panorama of the City project as a state one, with a reduction in "Polish" accents. The new panorama was to reflect the Ukrainian model of historic Lviv. In June 1945, the rights to the panorama were assigned to the Ukrainian Academy of Architecture, and Witwicki was appointed deputy director of this institution.

When Janusz Witwicki decided to move to Poland, the possibility of "compulsory sale" of his work was considered. In April 1946, the Panorama was declared state property. Three days before the planned date of Witwicki's departure, three men came to his workshop on vul. Virmenska and introduced themselves as journalists or art critics. The next day, July 16, 1946, the body of Janusz Witwicki was found on the street. His wife testified that she saw one of the "art critics" in the NKVD uniform. There was no show trial in this case. Two weeks later, Irena Witwicka and her daughters left for Poland and managed to take the Panorama in parts with them. Upon arrival in Warsaw, Panorama was placed in one of the rooms of the National Museum. However, due to the fear that the Soviet authorities would demand its return, it was decided to hide the Panorama in one of the basements of the Warsaw Polytechnic. Since September 2015, Panorama has been available for viewing at the Hala Stulecia exhibition complex in Wrocław.

Despite the fact that some of Polish cultural heritage artifacts were transferred to Poland in the postwar years, most of them remained in Lviv. In 1969, the Lviv regional committee estimated that there were "more than four hundred thousand works of art, history, and culture" in Lviv museums alone, of which only 6% could be accessed by public. Thus, post-war Lviv was overflowing with artifacts of the past that did not fit into the new Soviet ideology.

Sources

- Роман Голик. "Легенда львівського Оссолінеуму: постаті, видання та соціальна роль бібліотеки Оссолінських в уявленнях галичан ХІХ–ХХ ст.", Збірник наукових праць / НАН України, ЛННБУ ім. В. Стефаника, Львів, 2010;

- Пластична панорама давнього Львова. Януш Вітвіцький. Львів, 2003;

- "Historia powstania", Panorama Plastyczna Dawnego Lwowa, (режим доступу від 13.02.2019);

- Maciej Matwijów, Walka o lwowskie dobra kultury w latach 1945‒1948, Redaktor A. Zieliński, Wrocław: Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Ossolineum, 1996;

- Tarik Cyril Amar, The Paradox of Ukrainian Lviv: A Borderland City between Stalinists, Nazis, and Nationalists, Cornell University Press, 2015.