New Lviv residents and their city ID: 263

The story is a part of the theme The Epoligue of the War, prepared within the program The Complicated Pages of Common History: Telling About World War II in Lviv.

Story

My

father finished the war at the First Ukrainian Front. They went through

Belarus, Poland. It was rumoured that there were many vacant apartments in

Lviv. (...) And they stopped in some acquaintances’ place, and then my father

saw an announcement reading "Firewood for sale", on a road-post

there, at the Rohatka. This was a signal that not firewood was being sold but

an apartment (...) The Pole was one of those who did not have time to leave in 1945.

The family was going away and leaving the apartment, so he was happy to get at

least some money. There was a nice bed there, an iron one, resembling a lace…

And that stove — a green, light one. So we remained here.

(Interview

with V. H., whose family settled in Lviv in 1945, collection of the Center for

Urban History)

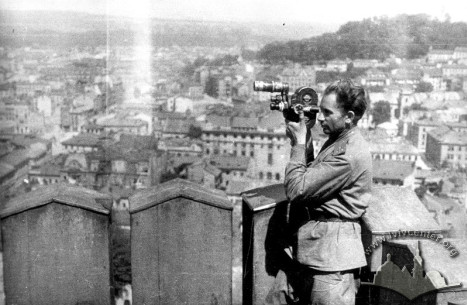

In the first years after the war, Lviv was a city where large-scale evictions and settlements took place simultaneously. Despite the rapid loss of Jewish and Polish populations, postwar Lviv quickly gained new residents — Ukrainians, Russians, and Soviet Jews. As early as July 1946, the Kyiv Central Committee recorded the population of Lviv at 352,013, slightly more than in 1939. As of 1949, about 70% of Lviv's residents came from other regions of the Soviet Union. According to historian Tarik Amar, new Lviv residents created new identities, but the strongest opposition in the public space of the postwar years was between "locals" and "newcomers" or "Easterners". There were also other important categories, such as party affiliation, Soviet social status, experience of living in German-occupied territory, experience of military service, categories of religiosity, age, gender, and, of course, ethnic and linguistic differences.

In Galicia, the extermination of Jews and the resettlement of Poles meant the loss of entire groups of specialists in various professions. Lviv was an important destination for a large-scale operation to recruit qualified personnel. Less than a year after Lviv accessed the Ukrainian SSR, the Kyiv Central Committee sent about 2,000 specialists in industry, communications and transport to the city; more than 1,200 for militia, courts and prosecutors; and 115 for key party positions. The peak of immigration came in 1945 and 1946, mainly people from Russia, eastern and central Ukraine, and other regions of the Soviet Union, as well as demobilized soldiers. As early as October 1944, fifty-seven of the seventy-three directors of large industrial enterprises were newcomers. The career opportunities of local residents under the new regime were very limited. They were mainly employed in low-paid jobs, low-ranking or minor management positions in small enterprises.

Higher education was a mobility tool as well: lots of students kept coming to the city. One-fifth of Lviv's post-war students were war veterans. In the 1944/1945 academic year, the number of first-year students was 2,200. Studying in Lviv was not necessarily voluntary as many students were sent to Lviv as an alternative to working at remote mines or factories. Locals were not excluded from the higher education system. As of 1950, almost half of Lviv's students came from Western Ukraine. At the same time, most of the teaching staff came from other regions of the USSR.

Post-war Lviv was also a destination for internal refugees fleeing the famine of 1946-47. Among the newcomers were those returning from forced labour in Germany and Ukrainians expelled from Poland. The Soviet Union, which had suffered heavy casualties, was interested in the return of war-displaced people, primarily to rebuild the postwar economy. An agreement on the mandatory repatriation of Soviet citizens was reached at the Yalta Conference in February 1945. Conditions of detention in repatriate camps were very difficult; their fate was uncertain. In total, the Lviv region was a major Soviet transit point, with about 350,000 repatriates passing through nine camps.

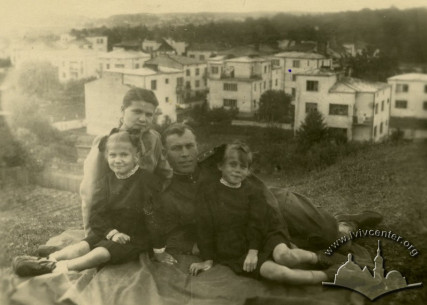

Lviv's housing suffered relatively little damage during the war: just about 15% of houses were destroyed and damaged. Post-war migrants inhabited Lviv apartments in various ways. Legitimate settlement required a housing warrant, which was issued for vacant apartments or after the eviction of previous residents. According to historian Halyna Bodnar, the best apartments were inhabited by newly arrived Soviet government officials, employees of the party apparatus and security services, servicemen, lawyers, doctors, and others. The central streets, the modern neighbourhoods of Kastelivka and "Altayski Ozera", vul. Pekarska and vul. Lychakivska, as well as the Professors' Colony were considered prestigious districts of the city. The Housing Department, the body that issued warrants for apartments, was established in November 1944 at the City Council. The warrant was considered valid for 10 (later 30) days after its issuance. During this time it was necessary to occupy the provided apartment and to pass the warrant to the house management office to be stored. Despite the ban, there were cases of unauthorized occupancy of apartments.

In 1945, Soviet soldiers were returning from the front via Lviv; some of them remained here for permanent residence. Former soldiers first settled themselves and later transported their families. Newcomers were often housed with Polish families, who later left. Officially, Poles were not allowed to sell their own homes. The vacated apartments were inventoried and transferred to the city authorities. At the same time, speculation on the black housing market was widespread. The housing department was also involved in these processes; eyewitnesses recall that a bribe was often required to obtain a warrant for an apartment. By the summer of 1945, the black market price for the right to move into a furnished apartment had increased 3-4 times (to 15-20,000 rubles). There was also barter; sometimes the right of real estate and furniture of possession was exchanged for products or other valuables:

Our

apartment was bought by Ivan Boyko from Kyiv. As such transactions could not be

done for money, he gave us many consumer products for our apartment, a whole

variety of them. My father, who was a lawyer, carefully wrote it all down and

had a whole list of what we got in two languages. Butter for the chair, and so

on. The only thing we couldn't trade was the piano. It could not be evaluated

in lard or other foods.

(Memoirs

of Leszek Allerhand, recorded on September 4, 2016; collection of the Center

for Urban History)

Despite the fact that the architecture of Lviv was almost not damaged during the war, the city's population changed dramatically. In the postwar years, a new society and new identities of Lviv were formed, which reflected the changing political realities. Over the following three decades, Lviv became a major industrial center, strategically important among other Western Ukrainian cities, and attracted new residents. There was a rapid urbanization, primarily due to migration of the Ukrainian rural population of the western regions. The urbanization was facilitated, on the one hand, by the industrial development of Lviv, which created additional employment opportunities, and, on the other hand, by the attractiveness and comfort of life in the city. In the 1950s and 1980s, the number of Lviv residents doubled.

Sources

- Галина Боднар "Розкіш і злидні повоєнного Львова, або реалії житлово-побутового повсякдення в омріяному місті", Україна Модерна, (режим доступу від 13.02.2019);

- "Пошуки дому" у повоєнному Львові. Досвід Підзамче, 1944-1960 - матеріали проекту, колекція Центру міської історії Центрально-Східної Європи;

- Софія Дяк, "Творення образу Львова як регіонального центру Західної України: радянський проект та його урбаністичне втілення", Схід-Захід:Історико-культурологічний збірник. Випуск 9-10, Харків, 2008

- Tarik Cyril Amar, The Paradox of Ukrainian Lviv: A Borderland City between Stalinists, Nazis, and Nationalists, Cornell University Press, 2015.