Education and Culture: Who Was Lucky? Halyna Levytska ID: 254

Foundation of the Lviv Conservatory. Story of Halyna Levytska as an example of a person involved in creation of Ukrainian Soviet culture despite the previous tragic experience of cooperation with Soviet rule.This story is a part of the theme about Soviet Occupation in 1939-1941, prepared as a part of the program The Complicated Pages of Common History: Telling About World War II in Lviv.

Story

In the late 1980s, new opportunities opened up both for historians and researchers and for history-hungry citizens: archives were opened, new books and sources of information from abroad became available, memories from the diaspora appeared in public. As a result, for Galicia, the period 1939–1941 began to be confidently called an occupation, the scale of repression was revealed to general public, forgotten names were coming back, memoirs were published, and new monuments were erected.These changes also had a converse effect: how to talk about artists, scientists, writers, etc., if they were not arrested, exiled or deported, but, on the contrary, were given new opportunities under the new regime? The term "occupation" is followed by new "accompanying" terms like collaboration, cooperation with the authorities, “government servants”, and so on. Since during the Soviet period the public space of Ukraine did not develop skills and abilities to speak on such topics, the result was either the absence of this period in the biographies and museum expositions, or very general and scarce information about it.

It is only now that public discussions and conversations have started on how to treat such biographies and what terminology would be appropriate here, what is collaborationism, what is coercion, and what is a survival strategy.

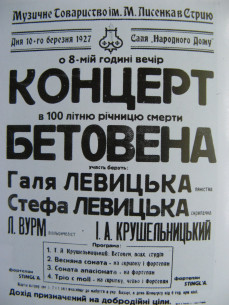

The Lviv National Mykola Lysenko Music Academy was founded in 1939 on the basis of several pre-war educational institutions: the Conservatory of the Polish Music Society, the K. Szymanowski Conservatory, the Higher Mykola Lysenko Music Institute and, partly, the Department of Musicology of Lviv University.

Halyna Levytska, a pianist and a teacher who saw the revealing of Ukrainian music as her mission, was an active participant in the reorganization of higher music education in Lviv. She was the first to perform for the local and foreign public little-known works by Mykola Kolessa, Pylyp Kozytsky, Levko Revutsky, Zinoviy Lysk and Stefania Turkevych-Lukiyanovych, the first Galician female composer.

It was Halyna Levytska who came up with the idea of creating a ten-year school at the Lviv National Mykola Lysenko Music Academy. One can read about the work of Halyna Levytska during the Soviet occupation in the memoirs of her daughter, Larysa Krushelnytska:

The Higher Lysenko Music Institute was liquidated, but the Lviv State Conservatory was opened on its basis and on the basis of the Polish Conservatory. My mother was engaged as a professor and head of the piano department. (By the way, she was also one of the first to receive confirmation of the title of professor from the Moscow Higher Attestation Commission in 1940). In addition, as soon as the Conservatory ten-year music school was opened, my Mom was appointed its director. Though for a long time she was in fact kept there as an acting director, she didn't pay attention.

The story of Halyna Levytska is interesting given that, unlike most Lviv residents, her Levytsky-Krushelnytsky family already had experience of cooperating with the Soviet regime, and the result of this experience was tragic. As it was quite difficult for intellectuals of national groups different than Polish to fulfil themselves in the interwar period, in 1932 Halyna's husband, Ivan Krushelnytsky, who was a Ukrainian poet, playwright, graphic artist, art critic and literary critic, as well as his parents, Ukrainian intellectuals Antin and Maria Krushelnytsky, and other family members together with little Larysa Krushelnytska went to Kharkiv, to the then Ukrainian SSR, where great opportunities for self-fulfilment and work for the benefit of the Ukrainian state seemed to open up. Of all those who left, only little Larysa survived and was rescued by Halyna Levytska to Lviv by hook or by crook, with the help of the Red Cross; she had remained in Lviv due to illness and had not been able to leave for the Soviet Union with her family.

Ironically, the trip to Australia in August 1939, where Halyna Levytska was invited to work at the Sydney Conservatory, was also postponed due to household issues and the health of Larysa, her daughter, so the famous pianist was in Lviv when World War II erupted.

According to Halyna Levytska's daughter, the dilemma of whether to work or not to work for the system was decided by her mother, as it was case with many Ukrainian intellectuals, in spite of all previous experiences, in favour of Soviet Ukraine, and the main argument was the need to create Ukrainian, though Soviet, structures. Krushelnytska recalls this as follows:

My Mom was engulfed in work. I remember her conversations (with Kyrylo Studynsky). "We need to seize the moment, we need to take over the university, the institute, schools, theaters..." he persuaded everyone. And indeed, at first it was so. Our professors could finally teach in Lviv universities, artists occupied theaters.

After the Nazi occupation, Halyna Levytska taught at the Conservatory; at the same time, she did not give up concert activities and together with her sisters, Maria and Stefania, performed as part of the Levytsky Sisters trio (piano, violin and cello) in 1946-1947. Halyna Levytska's students were, in particular, composer Andriy Hnatyshyn, People's Artist of Ukraine Oleh Kryshtalsky and others. The house on vul. Yefremova 49, where Levytska lived until her death in 1949, has a memorial plaque. She was buried in Lviv.

With the definition of the Soviet period of 1939–1941 in the history of Lviv as an occupation, it is difficult to fit the biography of Halyna Levytska into the binary "victim-collaborator" model. The Krushelnytsky-Levytsky family was one of the first to experience the repressive nature of Soviet rule even before the occupation of Lviv. Yet despite this family tragedy, Halyna Levytska not only did not leave Lviv, but also actively pursued professional activities in favour of developing the Ukrainian Soviet system of music education. Having made such a choice, she joined the Soviet project and became part of it. Creating Ukrainian Soviet culture, she formed herself, her career, her place in the new Soviet society. This biography is an example of how choices and identities can be superimposed, how the Soviet system, while controlling and dictating, at the same time provided an opportunity to fulfil oneself, how a certain agreement between the state and the person was formed in the new Soviet realities. It is a story of decision making, consequences, and responsibility. Also, it is a story about perception and understanding of such biographies and patterns of behaviour by contemporaries.

Sources

- Лариса Крушельницька, Рубали ліс. Спогади галичанки (Львів: Астролябія, 2008), 352.