The Church and the Holocaust ID: 205

The Greek Catholic Church, led by Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky, played a significant role in the rescue of the Jews of Lviv and Galicia. At the same time, complex discussion about the limits of leaders’ individual and collective responsibility in times of general extreme violence is still open.The story is a part of the theme Reactions of Lvivians to Holocaust, which was prepared within the program The Complicated Pages of Common History: Telling About World War II in Lviv.

Story

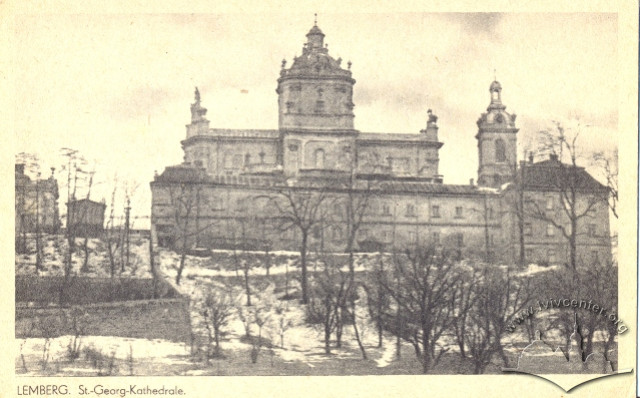

The Greek Catholic Church, led by Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky (1865–1944), played a significant role in the rescue of the Jews of Lviv and Galicia. At the initiative and with the approval of the Metropolitan, about 150 Jews, including children, were hidden in Greek Catholic monasteries. In the Second Polish Republic, Sheptytsky enjoyed considerable authority as one of the leaders of the Ukrainian movement. He maintained close ties with Jewish leaders, including the rabbi of the progressive synagogue in Lviv, Dr. Ezekiel Levin. It was Sheptytsky who rescued Rabbi Levin's two sons, Kurt and Nathan. In the Studite monastery in Lviv, he had Rabbi David Kahane hidden, as well as his wife and daughter. Today, the fact that Metropolitan Sheptytsky has not been recognized one of the Righteous Among the Nations is the most controversial one, although his brother Klymentiy, who was involved in organizing a network of aid to Jews, was awarded this title in 1995.

In Israel, the first request to the Yad Vashem for the title of Righteous for the Metropolitan was submitted by Rabbi David Kahane, who had been rescued by him. However, when a commission was convened on this issue in 1981, two of its thirteen members abstained, five voted for the title, and six were against. Since then, the commission has met several more times, but no consensus has been reached. Among the main reasons for the refusal are Sheptytsky's position on the Ukrainian nationalist movement and his cooperation with the Nazis during World War II (in particular, his congratulations to the "victorious German army" in 1941 and support for the SS Division "Galicia" through the appointment of Greek Catholic chaplains), as well as the possible impact of such decisions on the behaviour of UGCC believers. At the same time, the Jews rescued by the Metropolitan remain one of the most active "advocates" for conferring this title on Sheptytsky. Thus, in a letter to the Yad Vashem President dated November 24, 2007, Kurt Levin wrote: "The survivors include my brother Nathan Levin, the sons of Rabbi Hamaides — Professor Leon Hamaides and Professor Zvi Barnea, Professor Adam Daniel Rotfeld, Dr. Odd Amarant, Mrs. Lily Polman, the late Professor Podoshin, who are all making an incredible effort to achieve the recognition of Metropolitan Sheptytsky as Righteous." In their appeals, they emphasize primarily the humanistic and Christian motives of Sheptytsky's activity. It is worth noting that the Metropolitan was posthumously given a number of other awards and distinctions for rescuing Jews.

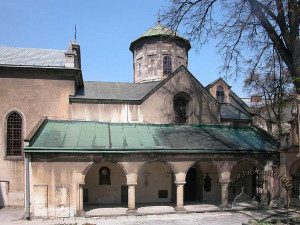

Historians and researchers of Sheptytsky's legacy draw attention to the fact that the difficult circumstances in which the Metropolitan was forced to make contradictory decisions are to be considered. Thus, the experience of Soviet repression in 1939-41 and the anti-religious nature of the communist rule surely became a factor in the initial perception of the Nazi occupation as a "lesser evil." Besides, Sheptytsky's support for the idea of a Ukrainian state led to the assessment of the Germans as likely allies in its development. Another important context is the pan-European debate over the Catholic Church's position on the Holocaust, including criticism of the passivity of the official Vatican and Pope Pius XII as to the Nazi policy of the extermination of Jews. Realizing the scale of Nazi terror, Metropolitan Sheptytsky was one of the few high-ranking church leaders who dared to speak out against it publicly. In addition to his famous pastoral letter "Do not kill" (November 1942), Sheptytsky also sent the Pope a letter on Nazi crimes in Galicia; according to some accounts, he wrote also to Heinrich Himmler protesting against the involvement of Ukrainians in the murder of Jews (the original letter has not been preserved). Other cases of individual assistance to Jews by Catholic priests in Lviv are also known. In 1943, Dionysiy Kaetanovych, the vicar of the Armenian Catholic Church in Lviv, was arrested after the Gestapo was informed that he issued Christian birth certificates to Jews. Metropolitan Sheptytsky and the papal nuncio intervened, but the vicar was released only after paying a bribe of 120,000 zlotys. The Roman Catholic clergy also joined the Council for the Aid to Jews Żegota activities, for example, making false baptismal records. To do this, they transferred blank forms, instructions on how to fill them in, as well as ready documents. At the same time, the attitude of Catholic clergy to the extermination of Jews was not uniform. For instance, Kurt Levin recalled that he had had to leave his hiding place in the Greek Catholic monastery on vul. Lychakivska because of the opposition on the part of one of the priests:

I

spent two weeks in a monastery at Lychakiv. One day Father Raphael returned

from a trip. He immediately turned his attention to me and watched me. He was a

young priest, a good artist who studied at universities abroad for a long time.

He was a man of Western culture and high intelligence. Unfortunately, all these

virtues faded when faced with his frantic anti-Semitism ... He immediately disclosed

me and demanded that I be expelled from the monastery immediately. He motivated

this by the fact that the complete extermination of the Jews was God's will,

and therefore aiding them was a protest against it. Father Marko and Father Tyt

took a completely opposite position, but Father Raphael threatened to denounce

me, so they had to transfer me to another place.

(Кurt Lewin. Przeżyłem. Saga świętego Jura

spisana w 1946)

The example of Metropolitan Sheptytsky and other church leaders during World War II opens a complex discussion about the pitfalls of anti-historicity (when past events are judged from the present-day point of view), dilemmas of choice, and the limits of spiritual and political leaders’ individual and collective responsibility in times of general demoralization and extreme violence.

Related buildings and spaces

Sources

- Мирослав Маринович. “Андрей Шептицький і дилема гуманістичного вибору”/ ZN.UA, 18 листопада 2005 (режим доступу 08.11.2018).

- Самвел Азізян, “Становище Львівської архідієцезії Вірменської католицької церкви під час Другої світової війни” / Східний Світ, 2016, № 4, с.29–40 (режим доступу 08.11.2018).

- Щоденник Львівського гетто. Спогади рабина Давида Кахане. Упорядн. Ж.Ковба. Київ 2009. Онлайн-доступ (режим доступу 08.11.2018).

- Martin Gilbert. The Righteous: The Unsung Heroes of the Holocaust, London, 2002

- Кurt Lewin. Przeżyłem. Saga świętego Jura spisana w 1946, Warszawa, 1996.

- John-Paul Himka. “Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky and the Holocaust”, Polin. Studies in Polish Jewry, vol. 26, 2014 (режим доступу 08.11.2018).

- Michael Phayer, The Catholic Church and the Holocaust, Indiana University Press, 2001.

- Szymon Redlich. “Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytśkyi, Ukrainians and Jews during and after the Holocaust”, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, 5/1 (1990), 39–51.

- Timothy Snyder, “He Welcomed the Nazis and Saved Jews”/ NYR Daily 21 December 2009 (режим доступу 08.11.2018)