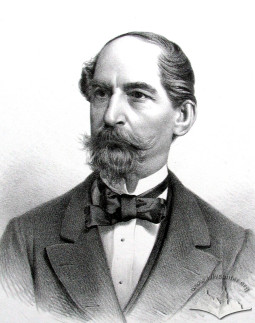

Florian Ziemiałkowski ID: 184

Florian Ziemiałkowski ID: 184

1817-1900

Polish politician and Austrian statesman, President of Lviv, lawyer.

Florian Ziemiałkowski (December 27, 1817 – † March 27, 1900) – Polish politician and Austrian statesman, President of Lviv, lawyer.

Born in the village of Mala Berezovytsia (now – Zbarazh district, Ternopil region) in the family of a poor cook at a manor estate. He graduated from Ternopil Jesuit High School (1827-1833) and from the Law Faculty of Lviv University (1834-1838). As a student, he had significant mental capabilities and exceptional vitality. In 1840, he obtained a doctor degree in law from Lviv University. During several months in 1841, he worked as an associate professor at the Law Faculty of Lviv University.

Ziemiałkowski participated in the Polish insurgent movement of the 1830-40s, and was sentenced to death (1845), but due to amnesty, he was released and stayed under police surveillance; in 1863, he participated in establishing a branch of Polish insurgent movement in Lviv in the framework of support for the January Uprising in the Polish Kingdom, and later he was one of the leaders of Polish Liberal Democrats in Lviv who advocated the transformation of Galicia into a broad Polish autonomy; President of Lviv (1871-1873); Minister for Galicia in the Austrian government (1873-1888), Deputy of the Austrian parliament in Vienna (1848-1849, 1867-1869, 1873-1888, and from 1888 - lifetime member in the House of Lords) and Halychyna Parliament in Lviv (1861-1863, 1867-1869, 1870-1895), Head of the Polish Club in the Austrian parliament (1867-1868).

His worldview and opinions evolved from revolutionary, liberal and democratic to moderately conservative and loyalist. The failure of the January Uprising as well as constitutional and decentralization transformations in Habsburg monarchy finally convinced Ziemiałkowski of a need for compromising with Vienna government concerning the internal restructuring programme of the Austrian monarchy (the political group headed by Ziemiałkowski was ironically called "Mamluks" by opponents). The peak of his popularity in Lviv milieu was reached at the turn of the 1860-1870s. Rejecting the broad autonomy for Galicia, Ziemiałkowski limited his claims to the Polonization of schooling, judiciary system and administration and supported the agreement of Polish elites with the Austrian government and the cease of mass patriotic actions. He represented the interests of Polish gentry from Eastern Galicia and richer city intellectuals. As President of the city, Ziemiałkowski sought to centralize power in the city and was a pragmatist and autocrat. He concentrated efforts on increasing the financial status of officials and improving the efficiency of municipal administration, particularly in the sphere of tax collection. During his presidency, there was created the City Bureau of Statistics. He treated his presidency as a temporary position and a step to the political career in Vienna. After his appointment of Minister, he distanced himself from Lviv political milieu. He shared anti-Ukrainian views. He treated a nation as "historical and political identity" and interpreted Ukrainians as part of the Polish nation. One of his most important tasks as Minister for Galicia was the supervision of contacts between Vienna and Ukrainian elites. He was married (from 1858) to Helena Dylewska (c. 1840 – † August 8, 1917), daughter of Marian Dylewski, Lviv lawyer and member of the Central National Council (1848). The Ziemiałkowskis did not have children. In Lviv, he lived in Striletska Square (now – Danylo Halytskyi Square). He died and was buried in Vienna, where the Ziemiałkowskis had lived since 1873.

Participant of Polish national movement

While studying in Ternopil and Lviv (1827-1838), Florian Ziemiałkowski was a member of Polish underground organizations and belonged to moderate middle management. As a student, he had significant mental capabilities and exceptional vitality. He was arrested and charged of belonging to the Polish national underground in 1845; later, he was sentenced to death, but due to amnesty, he was released and stayed under police surveillance. The revolutionary events of the "Spring of Nations" in 1848 involved Ziemiałkowski into the whirl of politics. During the next two decades, he along with Franciszek Smolka became the leader of Polish Liberal Democrats in Lviv who advocated the transformation of Halychyna into a broad Polish autonomy. He was a man of success. It was during the "Spring of Nations" when the features of Ziemiałkowski as a politician were revealed: his diplomacy, bias to backroom intrigues and backstage negotiations, oratorical talent, and, above all, moderate program and the ability to compromise with the Austrian government. He possessed an unfavourable attitude toward the concept of Slavonic solidarity in the struggle against the centralism of Vienna, supported a political union between Poles in Halychyna and Hungarians, and especially elucidated the negative role of Czech politicians who were inclined to support Ukrainian requirements for the division of Halychyna into ethnic areas.

In 1863, Ziemiałkowski participated in establishing a branch of Polish insurgent movement in Lviv in the framework of support for the January Uprising in the Polish Kingdom. Being an ideological opponent to insurgent tactics, he believed that since the uprising had not been prevented, it was necessary to join it in order to prevent the worst outcome which could be a social revolution. Along with Adam Sapieha, Franciszek Smolka and Alexander Dzieduszycki, he became a member of the insurgent Committee of Eastern Halychyna. Charged of participating in the organization of insurgent units in Lviv during July 1863, he was arrested and imprisoned in Lviv prison "Brygidky" till November 1865. The failure of the January Uprising as well as constitutional and decentralization transformations in Habsburg monarchy finally convinced Ziemiałkowski of a need for compromising with Vienna government concerning the internal restructuring programme of the Austrian monarchy. The peak of his popularity in Lviv milieu was reached at the turn of the 1860-1870s. In politics, he was close to Agenor Gołuchowski, backing the broadest autonomy for Halychyna, but avoiding a conflict with the Austrian government. In Lviv, he argued with Smolka and his supporters, who demanded the unconditional conversion of Habsburg monarchy into a federation of "historical" provinces.

President of Lviv

Rejecting the broad autonomy for Galicia, Ziemiałkowski limited his claims to the Polonization of schooling, judiciary system and administration and supported the agreement of Polish elites with the Austrian government and the cease of mass patriotic actions. At the turn of the 1860-70s, he and Smolka were key figures of political life in the city. In 1869, he proposed the establishment of a new newspaper in the city, later named as "Dziennik Polski". Ziemiałkowski managed to invite popular publicists Jan Lam and Henryk Rewakowicz to work in the editorial board. Gołuchowski financed the periodical and aimed at creating a Lviv conservative newspaper like "Czas" in Cracow which could unite moderate political forces among landowners and intellectuals, inclined to compromise with Vienna. Supported by the new periodical, Ziemiałkowski participated in the election to the parliament of Halychyna in 1870, and to Lviv City Council in January 1871. In April 1871, he was elected president of the city. According to the Polish historian Zbigniew Fras, "for poor and middle-class city residents where getry was still dominating, Ziemiałkowski was closer and more desirable due to his agility, moderate but secured success than Smolka along with his unfulfilled dreams and plans of big politics and big money that were more fit to Vienna than to Lviv"(Fras, 1991, s. 140).

As President of the city, Ziemiałkowski sought to centralize power in the city and was a pragmatist and autocrat. He succeeded in elaborating the regulations of the City Council, which made it possible to concentrate power in the executive committee, the so-called Department headed by the President. Thus, only a third of the city council had a real influence on decision-making. Ziemiałkowski reorganized the magistrate: he longed for increasing the financial status of officials and improving the efficiency of municipal administration, particularly in the sphere of tax collection. During his presidency, there was created the City Bureau of Statistics. Ziemiałkowski’s investment plans failed to find support among city officials who feared higher taxes. That is why the City Council often lacked a quorum. Ziemiałkowski also treated his presidency as a temporary position. His political ambitions were oriented at the Austrian capital. Ziemiałkowski stated gradually losing popularity among Lviv residents; after his appointment of Minister in April 1873, he quickly resigned from presidency and moved to Vienna.

Austrian minister

In 1873-1888, Ziemiałkowski was Minister without Portfolio (practically, Minister for Halychyna) in the Austrian government. Following the appointment of Minister, he distanced himself from Lviv political milieu. A gesture of break with Lviv and rapprochement with Cracow conservative groups was made during the 1873 parliamentary election when Ziemiałkowski refused from a parliamentary mandate of Lviv but accepted a mandate from the rural communities of Żywiec-Biala. In the early years of his office, he effectively acted as a mediator between the interests of Vienna and the Polish autonomy, focusing mainly on the involvement of state financial resources for the economic and educational development of Halychyna. He was a proponent of the concept "positive work". When Ziemiałkowski served as Minister, a new branch of economy – oil industry – developed in Galicia. His interests focused on social and economic matters (mediating talks between Vienna and Polish political elites in Galicia concerning the cancellation of Propination laws, indemnities etc.) and cultural and educational issues (opening Polish schools, the Polonization of Lviv and Cracow Universities etc.). He patronized Poles who sought for bureaucratic positions in the Austrian government.

One of his most important tasks as Minister for Halychyna was the supervision of contacts between Vienna and Ukrainian elites. Ziemiałkowski spoke for "equality" of Poles and Ukrainians, considering them to be one people divided by religion. He strongly opposed to Russian tendencies in Ukrainian movement, took steps to liquidate Greek-Catholic seminary in Vienna; he along with Peremyshl Bishop John Stupnytskyi supported Greek-Catholic priests from Kholm, who fled from there after the abolition of the Greek-Catholic Church (1875). He recognized the "delicate nature" of the Ukrainian question, but he saw the only way to resolve it by the linguistic assimilation and Polonization of Ukrainian population. After the death of the governor Agenor Gołuchowski (1875), he rapidly lost popularity in Galicia; after the appointment of Julian Dunajewski as Minister of Finance in 1880, in Vienna. As Minister for Galicia, he took a protective stance: he resisted unfavourable laws for Halychyna or minimized their impact on the region. He lost his post of Minister due to a conflict with Dunajewski.

"Ukrainian question" as viewed by Ziemiałkowski

The concept of the people-nation as a "historical and political identity" explains why Ziemiałkowski called himself a spokesman for the Ukrainians. He stressed that he had been "born in the Ukrainian land and was its native." This approach led to the interpretation of the Ukrainians as part of the Polish nation. In his memoirs, he raised the question: "Are the Ukrainians a nation? Our nation does not mean the same thing as tribe or people. In logic Polish, a nation has political significance and is often, and quite correctly, understood as a state" (Pamiętniki Floryana Ziemiałkowskiego ..., cz. IV, s. 192). Ziemiałkowski denied the possibility of immediate Ukrainian-Polish reconciliation as expected by some Polish politicians. He believed that the "reconciliation" could be achieved gradually by voluntary Polonization. He stated that "Polishness has some mysterious advantage over Ukrainness to the extent that a Ukrainian, who faced a Pole, is already getting more Polish" (ibid, p. 334). The existing Ukrainian-Polish conflict in Halychyna, which was actually caused by the formation of modern national movements, was explained as the heritage of the Commonwealth of Two Nations and the result of the Polish "religious fanaticism".

Ziemiałkowski’s position concerning the "Ukrainian question" are explicated via two groups of reasons: fearing the results of Ukrainian activities (Russia's growing influence, the administrative division of Halychyna, social conflicts between Ukrainian peasants and Polish landowners) and personal philosophical beliefs that, to some extent, were the product of liberal views. He considered that the Polonization of Ukrainian population is not the result of deliberate and organized actions but the influence of higher developed Polish culture. Therefore, from Ziemiałkowski’s viewpoint, legal equality for the Ukrainian and Polish languages would be against civilization progress. Later on, due to changing top-tank positions (president of the city, minister in the Austrian government), Ziemiałkowski’s ideological objections to Ukrainian identity were turned into political when his contacts with the Ukrainian movement were aimed at preserving the Polish dominance in Galicia, creating a pro-Polish group among Ukrainian intellectuals and transforming the province into a model of the future Polish state.

Works and projects

Related buildings and spaces

Organizations

Sources

- Центральний державний історичний архів України, м. Львів (ЦДІАЛ). Ф. 93: Земялковський Флоріан.

- Kazimierz Chlędowski, Pamiętniki, wyd. 2-ie uzupełn., do druku przygot., wstępem i przyp. opatrzył A. Knot, t. I: Galicja (1843–1880) (Kraków 1957), 532 s.

- Kazimierz Chlędowski, Pamiętniki, wyd. 2-ie uzupełn., do druku przygot., wstępem i przyp. opatrzył A. Knot, t. II: Wiedeń (1881–1901) (Kraków 1957), 504 s.

- Zbigniew Fras, FlorianZiemiałkowski (1817–1900). Biografiapolityczna (Wrocław, Warszawa, Kraków 1991), 228 s.

- Miasto Lwów w okresie samorządu 1870–1895 (Lwów 1896), LXXXIV+719 s.

- Stanisław Pijaj, Florian Ziemiałkowski a “kwestia ruska”, Przez dwa stulecia. XIX i XX w. Studia historyczne ofiarowane prof. Wacławowi Felczakowi (Kraków 1993), s. 35–49.

- Łukasz Tomasz Sroka, Rada Miejska we Lwowie w okresie autonomii galicyjskiej 1870–1914. Studium o elicie władzy (Kraków 2012).

- Damian Szymczak, Galicyjska “ambasada” w Wiedniu. Dzieje ministerstwa dla Galicji 1871–1918 (Poznań 2013), 362 s.

- Мар'ян Мудрий, “Зем’ялковський Флоріан”, Енциклопедія Львова, т. 2, за ред. А. Козицького (Львів 2008), с. 456–457.

- Кирило Студинський, “Листи мін. Фльоріяна Зємялковского до еп. Ступницкого”, Записки Наукового товариства імени Шевченка, т. LXXXV (Львів 1908), с. 106–133.