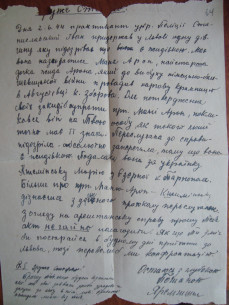

Ukrainian Auxiliary Police ID: 99

Ukrainian Auxiliary Police (ger. Ukrainische Hilfspolizei, UAP) was a police formation in the territory of the General Government, formed by the occupation authorities as an auxiliary police body in communities with predominantly Ukrainian population.

The history of the Ukrainian Auxiliary Police dates back to 17 December 1939, when, on the order of the Governor-General Hans Frank, to ensure order in the territories of the former Second Polish Republic, occupied by Germans, police on the basis of local population was created. Accordingly, Polish, so-called granatowa, that is, navy blue (by the distinctive colour of the uniform) and Ukrainian police forces were formed. These formations were financed by local self-government bodies and were directly subordinated to the local German Order Police (ger. Ordnungspolizei). At the request of the Ukrainian Central Committee, in December 1939 a police school (academy) under the leadership of SS hauptsturmführer Hans Krueger was set up in Zakopane to train Ukrainian policemen. By mid-1940, such academies were established also in Krakow, Chelm and Rabka. After the beginning of the German-Soviet war, many graduates of these police schools formed the basis of the Ukrainian Auxiliary Police formation in Western Ukraine.

From 1 August 1941 the legislation and administration system effective in the General Government were introduced in the territory of Galicia. Accordingly, the system of police forces, whose component was the Ukrainian Auxiliary Police, was also spread there.

In Lviv, the UAP was organized on the basis of the Ukrainian People's Militia, which had been disbanded. The process of the region's integration into the structure of the General Government stipulated the removal of local population from leading positions. As part of the concentration of power by the Germans, a process of gradual subordination of the "too independent" Ukrainian People's Militia, organized under the auspices of the OUN in the first weeks of the German-Soviet war, was started. On 2 August 1941, this structure became subordinate to the German authorities. From 12 August 1941, according to the order of the Orpo Commandant in Krakow, the Ukrainian Militia was disbanded, its participants being invited to enter the departments of the UAP. The latter's structural units were formed according to the city districts. In August 1941, six commissariats were formed and subordinated to the Main Command located on the second floor of the building on the Smolki (now Henerala Hryhorenka) square 3. Captain Emil Matla was the first commander of the Ukrainian police in Lviv, later replaced in this position by Major Volodymyr Pituley. His deputy was Liubomyr Ohonovsky, a former lieutenant of the Ukrainian Galician Army. With the expansion of the city's territory in 1942-1943, the number of the UAP commissariats was increased up to 11. Also, in May 1943, a separate commercial commissariat was formed in order to intensify the struggle against profiteering and more effective control of prices.

Each commissariat was responsible for a certain area of the city, conducting patrolling and guarding of objects in it. In addition, policemen were regularly recruited to work in other districts of the city and province to perform a variety of specific tasks typical of the Order Police (in particular, convoying Jews to the places of forced labour, participation in various roundups, anti-Jewish "actions" and periodic missions for guarding forced labour camps).

For the preparation and training of the UAP personnel in Lviv, the Police Academy was established in the city on Czysta (now Boy-Zhelenskoho) street 5. Both raw recruits and policemen who had already served in the UAP were accepted for training. According to the school curriculum, the policemen studied the German language, the basics of criminology, dactylography, techniques for conducting interrogations and photographing the crime scene, as well as a system of grades of the Wehrmacht and SS units. Regular firing practice took place on Kurkowa (now Lysenka) street. The first commandant of the school was Jerzy Walter, a volksdeutch, who was later replaced by one of the initiators of the UDP formation, Ivan Kozak, the chief of the UGA Field Gendarmerie in the past.

Personnel

The Ukrainian Auxiliary Police was formed mainly of peasants as well as the first-generation city dwellers. At first, the service in the UDP was seen primarily as a way of obtaining basic military skills and as a way of strengthening Ukrainian influence in the region in a situation of constant conflict with the Poles. Later, with the gradual disappointment in German policies towards Ukrainians and a radical decline in the authority of the police, the service in the UDP was more and more viewed solely in the light of material causes, as a way of earning, receiving benefits for the policemen themselves and for their families, and as protection from being taken for forced labour in the Reich.

The total number of the UAP personnel in the city was relatively small, fluctuating from several hundreds to a maximum of 860 in July 1943. From the late summer of 1943 till the last days of July 1944, the number of policemen was steadily decreasing due to poor popularity among the local population, loss of personnel and desertion.

Everyday activities

In their day-to-day work, UAP policemen performed the typical tasks of patrol police (street patrolling, processing applications, traffic regulation, primary detentions and transfer of offenders to relevant authorities (Kripo, Gestapo, SD, etc.).

As in other units of the patrol police, the service in the UAP was carried out in shifts in two groups, "A" and "B", which served on alternate days. The shift lasted for 24 hours, including 12 hours of patrolling, office work and at least 4 hours of rest. The working shift was dedicated to various current tasks, such as patrolling streets, sentry duty and regulation of street traffic, as well as guarding public institutions. Patrolling took place both alone and in pairs. After attacks against policemen became more frequent, on 16 February 1942 the command of the Ukrainian Police in Lviv banned the personnel from walking alone in the streets. Also, policemen were constantly accompanied by candidates for admission, who had studied or just graduated from the police school and had a term of probation.

In addition to streets, policemen, along with German gendarmes, patrolled commercial areas and approaches to the city. Since, in the conditions of war, the population of Lviv suffered from a constant shortage of food, the black market and speculation flourished in the city. Fighting against them and controlling prices were one of the UAP functions. However, withdrawing foodstuffs from "speculators" often turned into robbery of the local population at railway stations and in commercial areas, and in a number of cases the police were punished for these actions.

Along with guarding, the police often performed traditional police functions in criminal cases. This is indicated by protocols of testimony, complaints and reports from citizens regarding cases of hooliganism, thefts, robberies, finding unidentified bodies of those killed, etc. After verifying the information, depending on the offense nature, the police sent the case to the Orpo or to the Kripo. Here, the Ukrainian police worked closely with the Criminal Police and the German gendarmerie and performed the task of guarding the crime scene and keeping a record of testimony.

The role in the Shoah

As an integral part of the occupational police system, the Ukrainian Auxiliary Police was actively used to implement anti-Jewish policies in the region. The nature of its participation directly depended on the mentioned powers and the specifics of the patrol police daily work.

First of all, the detention of Jews during the day-to-day service on the city streets. The policemen were obliged to detain revealed offenders of the occupation legislation and to take them to the appropriate police authorities to pay fines or to be arrested. In the case of Jewish inhabitants of the city, ordinary offenses were supplemented with a number of specific violations: absence of the armband, presence in marketplaces in unauthorized hours, illegal stay outside the Jewish section, use of urban transport, and so on. With the introduction of a tougher anti-Jewish legislation in the autumn of 1942, any Jew or person suspected of being Jewish, found on the Aryan side of the city without special permission, was subject to immediate detention. It should be noted that UAP policemen detained Jews and their concealers not only in the streets of the city, but also during roundups and arrests in the apartments, in which they were involved as a power support for Kripo policemen.

Like other police officers, police officers of the UAP rather often used all these measures for self-enrichment. Despite the fact that for every detained Jew a policeman could receive an official reward, it was usually much more profitable to get a ransom on the spot. So it is not surprising that such earnings and bribery became quite a common practice among policemen of the UAP. It should also be noted that, in spite of rather strict conditions of service, in specific cases the behaviour of a patrol policeman depended largely on his personal position: he could either "ignore" an offender or find a formal reason for release, or tear actual documents, even quite legitimate ones.

The Jews detained on the street were usually convoyed straightaway to the Kripo administration (on the present-day Halytska square 15) or to the Administration of the Security Service (SD, on present-day Vitovskoho street 55). After registration, they were sent to the prison on Lonckiego street, and from there to the Yanivsky camp or directly "to the sands", i.e. to be executed.

In addition to the daily patrol service, from the first months of the German occupation the UAP policemen were actively involved in numerous roundups and capture of Jews for forced labour, and from the autumn of 1941 they were also involved in regular convoy service in the system of forced labour camps, the largest of which was the Yanivsky camp.

Nearly all district UAP commissariats of the city sent their policemen to the camps by rotation. Depending on specific circumstances, such a mission could take from several days to several months. At this time, the policemen resided in the territory of the camp complex and were directly subordinated to the camp administration. The service was carried out in day and night shifts. In general, policemen were involved in guarding and convoying. After the mission they were given a day off, an additional meal and additional food or cash benefits for their families. At one time there were no more than a few dozens of persons serving in the camp. All in all, given the constant rotation and staff turnover in the UAP itself, it can be assumed that during the occupation at least 150 UAP policemen from Lviv went through the service in the camp and its branches.

In addition, during the entire period of German occupation, they were actively involved in various anti-Jewish police operations (so-called "actions") both in the city and in other areas. As a rule, they were used for cordoning the area of the action and the main approaches to the city, as well as combing the "Aryan" districts of Lviv in search of enclosed Jews (along with the JOD, Zonderdinst, and Schupo).

In the very territory of the action, the most typical task for the UAP policemen was to convoy detained Jews to the concentration points and to provide their loading on the vehicles heading to the death camps. Significantly less often, policemen were involved in direct combing houses in the ghetto, which were rather often accompanied by blackmail and robbery.

In general, the UAP, as the largest mass patrol police formation in the city, played a significant role in the implementation of the anti-Jewish policies of the German occupation authorities. However, it should also be noted that anti-Jewish activities never played a key role in the work of the UAP.Related buildings and spaces

People

Sources

- Державний архів Львівської області (ДАЛО) Р.12/1/33:2-6.

- ДАЛО Р.12/1/40:4.

- ДАЛО Р.12/1/43:1-21.

- ДАЛО Р.12/1/45:15.

- ДАЛО Р.12/1/47:45,72 — Звіти ІІ Комісаріату української поліції з основної діяльності за червень 1942 – липень 1944 рр.

- ДАЛО Р.12/1/47:4, 104 — Звіти ІІ Комісаріату української поліції з основної діяльності за червень 1942 – липень 1944 рр.

- ДАЛО Р.12/1/52:59,77 — Звіти VI Комісаріату української поліції з основної діяльності за липень 1942 – липень 1944 рр.

- ДАЛО Р.12/1/54:17 — Звіти VIII Комісаріату української поліції з основної діяльності за січень-липень 1944 рр.

- ДАЛО Р.12/1/38:9, 11-14, 36-38, 41, 44, 51-52.

- ДАЛО Р.12/1/40:4,11,19,26.

- ДАЛО Р. 12/1/47:4 — Звіти ІІ Комісаріату української поліції з основної діяльності за червень 1942 – липень 1944 рр.

- ДАЛО Р.12/1/47:16, 104 — Звіти ІІ Комісаріату української поліції з основної діяльності за червень 1942 – липень 1944 рр.

- ДАЛО Р.12/1/84: 17.

- ДАЛО Р.12/1/124: 1-8.

- ДАЛО Р.16/1/1: 12-16.

- ДАЛО Р.16/1/14.

- ДАЛО Р.16/1/26: 1-17.

- ДАЛО Р. 16/1/29:41.

- ДАЛО Р.16/1/32:13.

- ДАЛО Р.23/1/1:1 — Накази управління про несення служби офіцерами.

- ДАЛО Р.23/1/6: 11-18 — Вказівки для караульної роти Команди Української Поліції у Львові.

- ДАЛО Р.23/3/4:1 — Накази управління про несення служби офіцерами.

- ДАЛО Р.23/3/6/11-18 — Вказівки для караульної роти Команди Української Поліції у Львові.

- ДАЛО Р.36/2/16: 1-7.

- ДАЛО Р.37/4/183: 21.

- ДАЛО Р.58/1/13:4, 11-13 — Конспект і записки по уставу внутрішньої служби Української поліції.

- ДАЛО Р.58/1/23:14-15 — Переписка по питаннях організації боротьби зі спекуляцією та заходами зі стеження за цінами.

- ДАЛО Р.58/1/30:11 — Циркуляри і переписка з питань організації та чисельності Української Поліції.

- ДАЛО Р.77/1/366:21 — Справа по звинуваченню Костирки Юлії в укриванні євреїв.

- ДАЛО Р.77/1/1111:5 — Справа по звинуваченню Романюк Анни та Бродковської Марії у наданні притулку євреям Арнольду Когусу, Сигізмунду Шайну та ін.

- ДАЛО Р.77/1/1160:2.

- ДАЛО Р.77/1/1227:2 — Справа по звинуваченню Цєплік Стефанії у переховуванні євреїв.

- Yad Vashem Archives M.49/801:7-8 — Kopelman Bolesław Testimony.

- YVA M. 52/252: 1-2.

- YVA M.52/253: 1-4.

- YVA O.3/2189:19-22 — Benedykt Friedman Testimony.

- YVA O.3/6819:6 — Ostrowska Helena Testimony.

- "Поліційний Розпорядок про утворення жидівських округ за мешкання в Областях Радом, Кракав і Галичина з дня 10 листопада 1942", Денник розпорядків для Генерального Губернаторства. Краків, 1943 (14 листопада 1942), №96, 673-676.

- Краківські вісті, 1941, 26 жовтня, 3.

- "Розпорядок про обмеження місця побуту жидів в Області Галичина від 1.09.1941", Львівські вісті, 1941, 5 вересня, Ч. 24, 4.

- Львівські вісті, 1941, 26 вересня, Ч. 42, 4.

- Львівські вісті, 1941, 12 листопада, Ч. 82, 3.

- Львівські вісті, 1941, 13 листопада, Ч. 83, 7.

- Львівські вісті, 1941, 13 листопада, 6.

- Львівські вісті, 1941, 25 листопада, 4.

- Українські щоденні вісти, 1941, 23 липня Ч.15, 4.

- Українські Щоденні вісти, 1941, Nr. 24, 1-3.

- Інтерв’ю з Вісловським Казимиром (1927 р. н.), проведене 10 листопада 2009 року у м. Львові.

- Gabriel Finder, Alexander Prusin. "Collaboration in Eastern Galicia: The Ukrainian police and the Holocaust", East European Jewish Affairs, 2004, № 34:2, 106-108.

- Dieter Pohl, Nationalsozialistishe Judenverfolgung in Ostgalizien 1941-1944 (München: Oldenbourg Verlag, 1996), 218-219.

- Ben Zion Redner, A Jewish Policeman in Lwów, Jerzy Michałowicz, trans. (Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 2015), 265, 267-268.

- Ryszard Torzecki, Kwestia ukraińska w polityce III Rzeszy 1933-1945 (Warszawa, 1972), 202.

- Володимир Кубійович, Українці в Генеральній Губернії: 1939-1941. Історія Українського Центрального Комітету (Чікаго, 1975), 37.

- Енциклопедія українознавства, ред. Володимир Кубійович та ін., Т. 3 (Львів, 1994), 1067.

- Тарас Мартиненко, "Українська Допоміжна поліція в окрузі Львів-місто: штрихи до соціального портрету", Вісник Львівського університету. Серія Історична, 2013. Вип. 48, 152-167.