Criminal Police ID: 98

Criminal Police (ger. Kriminalpolizei, abbr. Kripo) was a police force that operated in Nazi Germany and its occupied territories. The Kripo held investigations and engaged in operative and investigatory work in criminal cases.

Organization

Kripo branches were established in General Government territory during the first half of 1940. These branches were modeled after pre-war investigation departments in the Second Polish Republic as well as German criminal police departments. Together with the Gestapo, Kripo branches made up the Security Police (ger. Sicherheitspolizei) of the General Government.

After the General Government incorporated Galicia as its fifth district in August 1941, government officials began establishing civil and policing systems in the district. In Lviv, the district's capital, the General Government established the Directorate of Criminal Police (ger. Sicherheitspolizei und S.D. Kriminaldirektion Lemberg). German authorities initially placed the directorate alongside other police authorities on Smolki square 3 (now Henerala Hryhorenka), but soon they transferred it to a separate building on Halytska square 15.

Like directorates in other districts of the General Government, the Kripo directorate in Lviv was divided into two parts: "Polish" (non-German) and "German". Each division consisted of several commissariats (divisions) specializing in certain types of criminal offenses (murders, thefts, economic crimes, etc.). The German division had few members; in fact, they mostly supervised the activities of departments controlled by the larger Polish division. The German division only handled criminal cases involving persons of German origin or situations where "German interests" appeared to be violated. The "violation of German interests" ("actions directed against the German cause of the region rehabilitation") had a broad definition and could include a variety of behaviors and actions that either contradicted or did not fit the scope of state policy. These behaviors and actions included violating direct orders from German authorities, resisting German implementation of plans, assisting Jews (who were defined as state criminals under General Government law), and any unlawful acts committed on the territory of German institutions that resulted in damage of property. Like any ambiguous term, "violations" were often used with a speculative purpose, even in cases where German interests were not directly violated (ДАЛО P.35/6/228:6). Such direct offenses typically led to more severe punishments, including shootings or long term sentences in concentration camps (Majer, 2003, 497-498, 502).

The main, everyday tasks of the Criminal Police in Lviv were performed by the so-called "Polish Kripo". The chief of the Polish Kripo simultaneously served as the Directorate's deputy head and liaison officer, a position that coordinated the activities of the Polish and German divisions of the Directorate. In Lviv, this position was occupied by captain Jan Balicki (Hempel, 1990, 126), who occupied the position during the majority of the Nazi occupation (from November 1941 till July 1944).

Personnel

In general, Kripo branches in the General Government comprised of former members of the local departments of the pre-war Polish police (Dziennik Rozporządzeń Generalnego Gubernatora dla okupowanych polskich obszarów. Kraków, 1939, nr.1, 16; "Rejestracja funkcionariuszy b. polskiej pol. kryminalnej", Gazeta Lwowska, 1941, No. 19, 3). However, the majority of local police based in Eastern Galicia were eliminated by Soviet authorities between 1939 and 1941. This made it necessary for police officers from western districts – mostly Germanized Poles from Silesia – to move to Eastern Galicia and fill these spots. The Kripo also recruited volunteers to complete the police force. The Kripo's personnel – volunteer or conscript – had to be between the ages of 21 and 35, stand at least 1.65 meters tall, be physically fit and have a clean criminal record. In addition, Kripo candidates were required to undergo training at the Polish police school in Nowy Sącz in Krakow. Regardless, the Kripo's recruitment practices were less successful than expected (Gazeta Lwowska, 1941, No. 113, 5). In general, Lviv's Kripo branch remained small. In August 1942, for instance, the branch only included 272 persons.

Everyday activities

Kripo officers investigated criminal offenses – from petty larceny to armed robbery to murder. During the war, the "bandit" department (1st commissariat) were the most demanded part of the Kripo, as it investigated cases involving assassination attempts, armed attacks, robberies, and other serious crimes. The 1st commissariat fought criminal gangs as well as individual criminals. Due to the widespread availability of weapons in the region, Kripo officers — who typically wore civilian clothes — had to work with local uniformed police (especially Ukrainians) in raids and detentions. Since the 1st commissariat were assigned to establish the circumstances of cases involving suspicious deaths, they always had work to do during the occupation period.

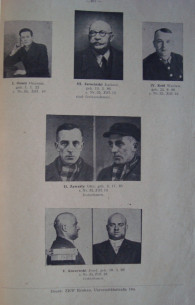

Kripo divisions that investigated thefts participated in a different line of work. Their activities were not based on using force but an active network of informants as well as frequent operations "in the field" (as, for example, Karol Leskiv's case concerning pocket thefts). In order to develop this network, the Kripo began publishing press releases calling for information on individuals involved in street thefts and robberies. In addition, Kripo officers asked for assistance from the general public in the identification of unknown bodies and the search for missing bodies.

Besides these types of crimes, Kripo officials also investigated instances of fraud, abuse of office, bribery — so-called "white collar" crimes — as well as violations of sanitation norms. The latter included cases that involved medical malpractice, deaths at the hands of medical workers, and the spread of sexually transmitted diseases.

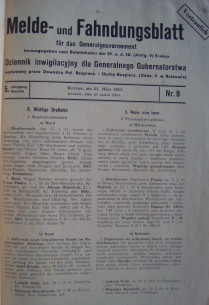

Kripo officers were also responsible for registering the occupied population as well as newcomers to the city (Gazeta Lwowska, 1943, No. 282, 3; Gazeta Lwowska, 1943, No. 123, 3). The sixth Kripo commissariat was specifically responsible for police registration in addition to searching for suspects and missing persons.

The role in the Shoah

While the Kripo mainly investigated criminal cases involving the local Aryan population, it also investigated offenses committed by Jews. Kripo investigations only involved Jews when the suspect was Jewish and had violated "German interests" or the interests of local Aryans living in the city.

With the tightening of anti-Jewish legislation, "illegal residence outside the Jewish district" was added to ordinary criminal offenses (robbery, murder, or theft) ("Обмеження побуту в Ген. Губернаторстві. Кара смерти для жидів поза дільницею", Львівські вісті, 1941, nr. 72 , 3). After the autumn of 1942, when the Jews were finally moved beyond the legal framework, this was the only subject of the Criminal Police proceedings. In addition, such a formulation of "crime" was also used after the Jewish district was eliminated in 1943.

It was through the hands of the Kripo that the lion's share of all Jews detained on the Aryan side and Aryans (Poles and Ukrainians) who helped them passed. They were delivered to the Police Directorate on the Halytska square both by primary level police units (UAP, Sonderdinst, Schupo) and civilians. Since Jews outside the ghetto were equated with dangerous state criminals at the level of armed bandits and members of the anti-German resistance movement, a reward was provided for their custody, which, depending on the time and circumstances, ranged from 200 zlotys in the middle of 1942 to 1,000 zlotys (three average salaries) in the spring of 1944 (ДАЛО Р-239/2/63:14).

The Kripo handled the majority of Jewish detentions in the city with the assistance of Polish and Ukrainian residents. Both primary-level police units (UAP, Sonderdinst, Schupo) and civilians delivered Jews to the Police Directorate on Halytska square. Civilians were given a reward for helping detain Jews since Jews living outside the ghetto were perceived to be as dangerous as armed bandits, anti-German resistance fighters, and other state criminals. This reward varied from 200 zlotys (given in mid-1942) to 1,000 zlotys (spring 1944), which was equal to three average salaries in Lviv at the time (ДАЛО Р-239/2/63:14).

Kripo officers also searched independently for hidden Jews, typically using facts taken from their network of informants (Hempel, 1990, 178-179). When detaining a person, all his or her belongings were described and withdrawn. This dual process incentivized officers to rob and/or blackmail their detainees before delivering them to the police. Despite being criminal offenses, blackmail and robbery became widespread practice among Kripo officers (YVA O.62/418:3-4).

Once detained, Jews were transferred either to the investigatory jail on Lanckiego street or the police directorate. Unlike their concealers — who remained in jail until their trial ended — Jews were immediately sent to the Janowska camp where they were either shot immediately or sent to work in the camp.

Related buildings and spaces

People

Sources

- Державний архів Львівської області (ДАЛО) Р.35/6/228:6 — Оголошення та розпорядження Львівського міського староства;

- ДАЛО Р.37/5/61:20 — Бюджети Управління поліції та української поліції у Львові на 1943/44 рр.;

- ДАЛО Р.58/1/29 — Циркуляри з питань постачання Української Поліції;

- ДАЛО Р.77/1/196:94 Справа по звинуваченню Кароля Леськова у кишенькових крадіжках;

- ДАЛО Р.77/1/595:2-3 — Справа по звинуваченню Грабовської Софії в образі поліцейського;

- ДАЛО Р.77/1/1227:3 — Справа по звинуваченню Цєплік Стефанії у переховуванні євреїв;

- ДАЛО Р.239/2/63:14 — Спостережне провадження по справі Гех Казимира Андрійовича та Деркач Стефанії Мартинівної обвинувачених у видачі німецьким окупаційним владам громадян єврейської національності;

- Yad Vashem Archive (YVA) M.49/2082: 2-3 — Klarfeld Charlotta Testimony;

- YVA O.62/418: 3-4 — Jakub Reiter Testimony;

- "Обмеження побуту в Ген. Губернаторстві. Кара смерти для жидів поза дільницею", Львівські вісті. 1941, ч. 72, 3.

- "Повідомлення Кримінальної Поліції", Львівські вісті, 1941, ч. 65, 3;

- "Повідомлення Дирекції Кримінальної Поліції у Львові", Львівські вісті, 1942, ч. 216 (340);

- "Увага! Убивство! Незнаний жіночий труп! Нагорода 2.000 зл.", Львівські вісті, 1942, ч. 231 (355), 5;

- "Повідомлення Дирекції Кримінальної Поліції у Львові", Львівські вісті, 1942, Nr. 216, 3;

- "Крадіж машини до писання", Львівські вісті, 1943, ч. 86 (506), 7;

- "Морд", Львівські вісті, 1943, ч. 226 (646), 8;

- "Rejestracja funkcjonarijuszy b. polskiej pol. kryminalnej", Gazeta Lwowska, 1941, Nr. 19, 3;

- "Nasza skrzyńka pocztowa", Gazeta Lwowska, 1941, Nr. 113, 5;

- "Wypadek uliczny i ucieczka kierowcy", Gazeta Lwowska, 1942, Nr. 182, 3;

- "Zastrzelenie polskiego urzędnika kryminalnego", Gazeta Lwowska, 1943, Nr. 53, 3;

- "Obowiązek policyjnego meldowania się na obszarze miasta Lwowa", Gazeta Lwowska, 1943, Nr. 128, 3;

- "Obowiązek meldowania osób przebywających w hotelach, szpitalach itp.", Gazeta Lwowska, 1943, Nr. 282, 3;

- "Odezwa wyższego dowódcy SS (Schutzstaffel) i policji w Generalnym Gubernatorstwie dla okupowanych polskich obszarów z 30 października 1939 r.", Dziennik Rozporządzeń Generalnego Gubernatora dla okupowanych polskich obszarów, Kraków, 1939, Nr.1, 6;

- "Komunikat", Gazeta Lwowska, 1943, Nr. 300, 3

- Gazeta Lwowska, 1944, Nr. 46, 4;

- Adam Hempel, Pogrobowcyklęski: rzecz o policji "granatowej" w Generalnym Gubernatorstwie 1939-1945, (Warszawa, 1990), 435;

- Eliyahu Jones, Żydzi Lwowa w okresie okupacji 1939-1945, (Łódź, 1999), 293;

- Diemut Majer, "Non-Germans" under the Third Reich… (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003), 1033;

- Кость Паньківський, Роки німецької окупації, (Нью-Йорк-Торонто, 1965), 400