Fraternal Aid Society of the Polytechnic School students (Stowarzyszenie Bratnia Pomoc studentów Politechniki Lwowskiej) ID: 134

The Society began operating in 1861, officially in 1867. It was founded after the pattern of a similar society in Warsaw primarily to support poor students; over time, however, its activities also expanded to scientific sphere as well as to that of politics. It was the largest and most numerous association of polytechnic students functioning until 1939.

The Austrian authorities considered student associations first and foremost a threat to public order. As early as the 1830s, the police constantly monitored students of Lviv University, exposing and arresting participants in unauthorized gatherings. Students often established links with the democratic movement (in the days of the still absolutist Austrian Empire), opposing, on the one hand, the government bureaucracy and, on the other, the people, while associating themselves with burghers and artisans. In 1848, during the Spring of Nations, the students of the Franz I University and the Technical Academy in Lviv were among active revolutionaries: they took up arms and formed the so-called Academic Legion. The army suppressed the uprising, bombarding the city, and it was the buildings of the University and the Academy that were destroyed in the first place. However, it was not only in Lviv that the students took part in fighting: some of them were imprisoned or sentenced to death for participating in the Hungarian Revolution.

In 1861, when several students gathered informally in one of the Academy's drawing rooms after classes, Director Alexander Reisinger stopped them to not let the police do it instead of him. Even 30 years later, in the 1890s, when the situation eased considerably, students had to notify the police in advance about any their meeting, even one held in the building of the Higher Technical School with the rector’s knowledge and approval; in their opinion, it was a violation of their rights as citizens and as representatives of the academic community. However, it should be noted that these rules applied to all societies and public organizations in Austria-Hungary, moreover, no meeting could be held without a police representative, so students were equal to other citizens and were not treated in some special way.

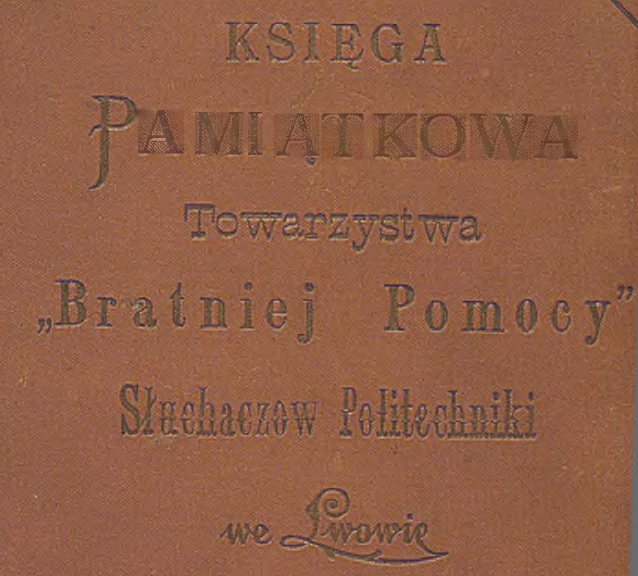

Officially, the first student attempts to unite pursued the intention to provide mutual help and to support poor colleagues. In 1897, writing its own history, the Society incorporated into its prehistory the informal "Bone Gnawers Society" from the 1840s, which allowed several students to have meals with the help of their colleagues. In general, this story emphasizes in every way the plight of most students, who always needed some extra earnings, or the fact that the first meetings were held in a room that was "small, low, almost never heated and poorly lit, the home of several poor colleagues" (Sprawozdanie, 1897, 23). It was activities of a purely humanitarian nature that were allowed in 1862 by the governor of Galicia, General Alexander von Mensdorff-Pouilly, known for his participation in the Austro-Italian war and in the suppression of the Hungarian Revolution in 1848-1849. It was in this way that the Fraternal Aid Society of the Technical Academy Students was formed (pol. Towarzystwo "Bratniej Pomocy" Słuchaczów Politechniki we Lwowie). Their first charter was approved by the Ministry of Religion and Education and then by the governorate in Lviv in late 1866.

Formally, each student, regardless of his ethnic or religious background, could be a member; the society was led by a committee of seven representatives from different years and a head who was elected by the members; curators from among the Academy professors were also appointed. The society ran a cheap student canteen and provided loans to needy students, collected a library of technical literature, published textbooks based on lectures by their professors (handwritten and lithographed). Some circles were formed within it — scientific, literary, and others, where reports and discussions were arranged. The members also engaged in leisure activities, including holding balls, which were a source of income for other activities. According to the press, these balls, held mostly in the City Casino on ul. Akademicka, were quite popular.

The Society existed due to membership fees but sought all opportunities for additional funding: it applied to the authorities for subventions, arranged amateur theater productions and concerts as well as balls. In 1895, the Fraternal Aid helped open the first dormitory in Lviv — the House of Technicians, where those members of the Society, who so desired, could settle for a small fee.

In addition, the Fraternal Aid defended the needs of students before the authorities like the management of the School and the Ministry of Education. Their delegates took part in congresses of students of Austrian polytechnics, which resulted in petitions and personal audiences with ministers to legitimize the common demands of all Austrian technical students, concerning such things as examinations, graduate titles and things that affected future employment. These issues were mostly common to all students, graduates, and professors of higher technical education, a field that was at that time just gaining public recognition compared to the status of humanities education in universities, as evidenced by the Dźwignia and the Czasopismo techniczne, periodicals published by the Galician technicians. Instead, historian Kazimierz Rędziński emphasizes the students’ cooperation with radical and socialist circles as the main reason for defending their rights, which was particularly evident in the student council of 1889 (Rędziński, 2014, 442).

Throughout the period from 1844 to 1918, the main requirement of the students was to equalize the status of higher technical schools with that of universities. This included the reorganization of examinations so that graduates would receive a doctorate in engineering and, along with it, the corresponding political and social rights and privileges. Besides, it was about the change of the assessment system to a three-level (excellent, good, bad) one as in the university in contrast to the five-level one as in the polytechnic, since the current situation caused misunderstandings in communication with potential employers. In addition, one of the demands was the introduction of humanities and social sciences that were not studied (for example, sociology, which had just appeared at that time) as well as the equalization of scientific programs in different schools of the Austrian Empire to facilitate transfer from one institution to another. Students sought liberalization, the recognition of their civil liberties and the reduction of police control; they wanted to simplify the complicated process of obtaining a discount on tuition or exemption from payment and demanded the state to finance obligatory study trips, in particular, that rail travel during these journeys be free.

Nevertheless, the Society was increasingly involved in politics beginning from the 1880s. According to its members, the period of the 1850s-1860s, after the revolutionary 1840s, was a time of "quiet work." In 1872, the students held the usual ball without any reservation, while local Polish conservative circles considered it unacceptable given the "national mourning" because of the centenary of the first division of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, so they planned an attack. As the information reached the police, the leaders, including Karol Groman and Jan Dobrzański, editors of the newspapers Dziennik Lwowski and Dziennik Narodowy, were arrested. Instead, in the 1880s, after the Higher Technical School was allowed to accept foreign applicants, a new expanded charter of the Society was adopted in 1881, and a large number of Poles from Congress (Russian) Poland moved to Lviv, including students who brought "a whole bunch of concepts and beliefs that amazed the Galician youth, buried in the sciences that were purely part of their profession." So the Galicians, who "had no idea what [Herbert] Spencer, [Auguste] Comte, [Karl] Marx, [Ferdinand] Lasalle, and others had written," got new interests, the fact first of all causing the reform of the Fraternal Aid's library collections. During the 1880s, students made reports on positivism, Darwinism, women's emancipation, economics, and an increasingly marked bias toward social democratic policies eventually led to tensions with another group of students who were conservative and religious in spirit. Finally, in 1906, the Mutual Aid Society of the Polytechnical School Students (pol. Towarzystwo wzajemnej pomocy słuchaczów Szkoły Politechnicznej), informally Wzajemniak, whose members had rather national-democratic preferences, separated.

Various circles were formed within the Society, one of the most notable being the Circle of Scientific Encouragement (pol. Kółko zachęty naukowej) where reports and discussions were actually held. In 1898, a separate Society of Ukrainian Students Osnova was formed; in 1908, the Society of Mutual Aid of Jewish Students emerged.

At first, the Society held its meetings in the rented apartments of its members, until the construction of the Polytechnic building was completed in 1877, where they received a room on the third floor.

In general, during the period before the First World War, the activities of the Society were important and significant for students, so it included more than half of all students, comprising different ethnic groups, political preferences, etc.; however, in the early 20th century there were more and more conflicts and tensions, both among the students and with the professors and administration of the institution, as well as the authorities, including the Galician governors.

Related buildings and spaces

Sources

- Kazimierz Rędziński, "Stowarzyszenie Bratnia Pomoc studentów Politechniki Lwowskiej (1861-1918)", Prace naukowe Akademii im. Jana Długosza w Częstochowie. Rocznik Polsko-Ukraiński, t. XVI,2014, s. 423-443

- Księga pamiątkowa Towarzystwa "Bratniej Pomocy" Słuchaczów Politechniki we Lwowie, (Lwów, 1897), 285

- Album inżynierów i techników w Polsce, t. I., cz. II, "Towarzystwo bratniej pomocy studentów Politechniki lwowskiej, (Lwów, 1932), 24

- XXXIV Sprawozdanie wydziału towarzystwa "Bratniej pomocy" słuchaczów Politechniki we Lwowie za rok administracyjny 1894/1895, (Lwów, 1895).