Lviv Organization of the Union of Soviet Writers of Ukraine ID: 2

It was the key institution of official literary life in Soviet occupied Galicia. It functioned from 1939.

The establishment of the Lviv Organization of the Union of Soviet Writers of Ukraine was started in October 1939, during the second month after the occupation of the city. It took the Organizing Committee almost a year to transfer the local literary life onto a Soviet trail. In September, 1940, a lengthy "organizational" stage was completed with the procedure of accepting the preliminary registered writers as full-fledged members of the Union. In addition, the board of the Lviv Organization was elected. The institution's activities can be viewed as an illustrative example of Sovietization of cultural life in Galicia.

Functions

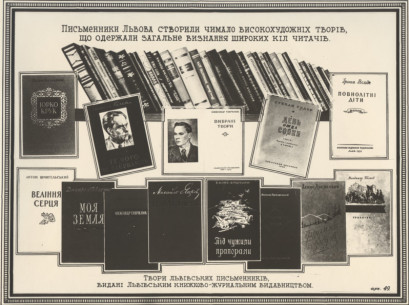

De facto, the Union of Soviet writers operated as a party controlled union, a monopoly that granted its members access to the publishing houses and gave the priority right to publish their works. Instead, it required them to be politically loyal and keep to the unified artistic method of social realism. Such an approach to the organization of literary life was essentially different from the situation in prewar Galicia where there was an entire range of writers milieus which centered mostly around periodicals that were pursuing different aesthetic, ideological, or political programs. Owing to that, there existed a field for effective discussions. And the new Union of Writers was aimed to unite men of letters under its command and supervision. The economic aspect had a significant role to play in this respect since having no membership in the Union meant no opportunities for professional activities for writers.

During the first months, the Organizing committee took record of almost everyone who had at least any formal relation to literature. According to the Union head Petro Panch, total number of the recorded authors was circa 250 persons (about 60 Ukrainians, almost 150 Poles, 38 Jews and 8 representatives of other nationalities). An official admittance procedure that granted membership in the Union took place after a year, on September, 15, 16, and 18, 1940. The membership application process was quite a ritual. The candidate had to prove his or her compliance with the image of a Soviet writer in its course. Sometimes, such as in the case with the Ukrainian writer Mykhaylo Rudnytskyi, the procedure was an opportunity for some local figures to settle old scores, and also a chance to exert moral pressure from the functionaries of new authorities[[quote|8]]. Another dramatic case was when the application from a Polish author Jan Brzoza was being considered, even though he had belonged to the milieu of leftist writers. Brzoza recalls the episode with open indignation[[quote|66]]. As a result, a formal institution was established that included writers with different convictions and of different nationalities who used to have few contacts in the past but now were forced by a twist of fate to jointly participate in the literary life, which was not always purely formal[[quote|9]].

The main task of the Organizing committee was to establish control over the men of letters present in Lviv at the time. It meant removing undesirable persons, and bringing the rest over to cooperate with authorities. The institution managed the censorship as with the arrival of Soviet administration, independent publishers and periodicals were liquidated. Thus, in order to publish works in Soviet publications one needed to receive consent of the administration of the Organizing committee. After all, it was the head of Lviv organization of the Union of Soviet Writers Oleksa Desniak who also headed the only literary magazine in the city, Literatura i Mystetstvo (Literature and Art), established in 1940.

At the same time, the Organizing committee also had a Writers Club, the main legal platform to hold meetings, lectures, and be the venue for more or less free communication for colleagues.

In terms of structure, the activities of the organizing Committee, and thus of the Lviv Organization of the Union, were based on national and generic principles: there were sections for prose, poetry and drama in each of the three languages. Participation in the work of sections was mandatory and public. Authors had to recite their works, then collective discussions would follow. During the discussions, the author would receive remarks on his or her deficiencies, especially the ideological ones. The compulsory collectivism of the creative process was one of the most traumatic experiences. In fact, it was the basis for the method of a Soviet writer. In addition, it was mandatory for the Union members to attend different events, such as lectures on Marxist theory. Besides, writers were grouped into brigades sent to different institutions to hold public speeches. Usually, the brigades included Ukrainian, Polish and Jewish members. The events would sometimes be on the brink of common sense, as, for example, described by an anonymous author in the recollections Inzhenery Lyudskykh Dush (Engineers of Human Souls).

The Writers Club also had a library were books from private collections and the dissolved Literary Artistic Circle were collected. According to Jan Brzoza, all books were thoroughly sorted out in accordance to Soviet quality criteria. The final decision about their destination was made by Yaroslav Tsurkovskyi. On the one hand, some books could be expropriated on quite formal grounds. On the other hand, relation of the author to some books could crucially affect his or her fate. In fact, Brzoza notes that he was "trying hard to save the friends"[[quote|68]].

Members of the Union of Writers were obliged to respond to all important events of Soviet life, such as elections to the Supreme Councils of the Ukrainian SSR and the Soviet Union; the anniversary of "liberation of West Ukrainian lands"; or various jubilees. Every time, authors had to prepare artistic or publicist texts on the particular subjects. In the literary history of the first Soviet occupation of Lviv, there were two cases of collective composition of poems : Pro ridnoho velykoho Stalina (On the Dear Great Stalin), successfully composed for the birthday of the leader on December, 21, 1939; and the failing poem Shchaslyvyi rik (The Happy Year) to commemorate the first anniversary of Soviet authorities in power.

At the same time, the Union provided for everyday needs of the writers, such as catering (the Union had a canteen) and some financial assistance. Under the auspices of the Organizing Committee, there was a Literary Fund (first headed by Ivan Honcharenko, later by Yuriy Shovkoplias). It was to support writers in difficult times, such as in wintertime.[[quote|12]] [[quote|13]] The writers had an opportunity to receive money from the fund, as well as fuel, food, and clothes. Alexander Wat who was in charge of registering the writers applying for the Organizing committee, recollects that a lot of the refugees from the West of Poland arrived to Lviv in a rather destitute state. It was the major reason for them to join the Union of Writers, even though they might have run a risk in the eyes of Soviet security agencies, due to their background.

People

It is typical that the Organizing committee, and thus the newly created Lviv Organization of the Union of Soviet Writers, was headed by the newcomer functionaries, such as Petro Panch and Oleksa Desniak. Galicians actually were holding the positions of associates, or assistants. It was a typical practice that fixed hierarchy relations between the newly arrived Soviet citizens and the liberated local population. Regular membership could relatively be divided into the five major groups: 1) the leftist writers, including Ukrainians, Poles, and Jews who were ideologically the closest, thus not feeling secure in the face of new regime, the same as many others [[quote|15]]; 2) influential figures of the prewar Lviv (the new regime needed their authority to reinforce its legitimate nature) ; 3) young writers who were most proactive, probably due to their young age (the new situation did not close so many opportunities for them as for the old writers who were ingrained in the prewar life)[[quote|16]]; 4) refugee Poles who fled German occupation and needed to settle their financial problems in the first place [[quote|17]]; 5) the writers who came in big numbers from Soviet Ukraine and Russia with a more or less official and pragmatic goals: some of them came with a specific working assignment or to participate in mass events; others came on their own will. At times, the arrival of the writer was a happening in the literary life (Arkadiy Lubchenko[[quote|18]], Volodymyr Sosiura), while at other times it was not (Maksym Rylskyi[[quote|19]]), when they were rather like commercial travelers because in the recently occupied Lviv one could buy many goods that were in deficit in Soviet reality[[quote|20]].

Premises

At the beginning, the Organizing committee, according to Panch, operated in the building of the City Casino at ul. Akademicka, 13 (now prosp. Shevchenka, 13) that used to function before the war as a club of Polish literary men and artists, the Koło Literacko-Artystyczne (Literary Artistic Circle)[[quote|37]]. However, soon after, the writers left the "habitable" premises that were transferred into the administration of the Red Army officers. Instead, the Organizing committee moved to the family palace of the Bielski counts at ul. Kopernika, 42 (presently known as the House of Teachers). It was a turning point in the history of the building and was also symbolic in the context of Soviet ideology: the private space of aristocracy was turned into a public place to serve proletarian culture[[quote|5]]. Initially, they allocated the ground floor to serve the needs of the men of letters, while the upper floor was left to the previous owners. The coexistence would generate some anecdotic situations. For instance, when a newly arrived Soviet writer asked to take him upstairs so that he could see a living count in his own eyes[[quote|7]]. Later, the count family was evicted and eventually deported to Kazakhstan, so the Organizing committee occupied the remaining premises as well. A new identity of the building as a public space of culture was fixed in the postwar period and preserved in the period of Ukraine's independence.

People

Sources

Sources

- Materials of the newspapers Vilna Ukrayina and Czerwony Sztandar.

- Остап Тарнавський, Літературний Львів, 1939-1944: спомини (Львів, 1995), 16–53.

- Петро Панч, "Львів, Коперника, 42", Вітчизна, 1960, № 2, 171–180.

- Інженери людських душ, Західня Україна під большевиками: збірник за редакцією Мілени Рудницької (Нью-Йорк, 1958), 205–217.

- Михайло Рудницький, Письменники зблизька (спогади) – (Львів, 1958), кн. 1; (Львів, 1959), кн. 2; (Львів, 1964), кн. 3.

- Спогади поета Романа Купчинського про приїзд до Львова групи українських письменників з Києва восени 1939 р., Культурне життя в Україні. Західні землі: документи і матеріали. Volume1: 1939-1953 (Київ, 1995), 126–132.

- Jan Brzoza, Moje przygody literackie (Katowice, 1967), 88–102.

- Aleksander Wat, Mój wiek: Pamiętnik mówiony (Warszawa 1990), 263–305.

- Andrzej Miłaszewski, "Pamiętam tamten pałac", Cracovia Leopolis, 1999, № 3, 14–17.

- Микола Ільницький, Драма без катарсису, На перехрестях віку (Київ, 2008), кн. ІІ, 354–381.

- Agnieszka Cieślikowa, Prasa okupowanego Lwowa (Warsaw, 1997).

- Joanna Chłosta, Polskie życie literackie we Lwowie w latach 1939-1941 w świetle oficjalnej prasy polskojęzycznej (Olsztyn, 2000) 69–87.

By Viktor Martyniuk

Translated by Svitlana Brehman