One of the main principles in implementing the Nazi plan to separate, control and exterminate the Jews consisted in gaining the support of the local non-Jewish population. For achieving this, the Nazis used propaganda. Before World War II, the Eastern Department was established within the structure of the German Ministry of Education and Propaganda, the main task of which was to propagate the struggle against Bolshevism. The team of the Eastern Division set up headquarters for all language groups in the Soviet Union. Their main duty was to create propaganda materials and distribute them in the occupied territories. The propaganda used the image of a Bolshevik Jew, a Ukrainophobe, who not only supported the Soviet government but also caused the mass murder of Ukrainians or Poles in 1939-1941.

The image of a Bolshevik Jew was widespread in Central and Eastern Europe on the basis of an anti-Semitic belief in a Jewish conspiracy aimed at world domination (the so-called Sages or Elders of Zion). Prior to the war, the majority of Jews were a religious and traditional society that saw communist atheism as a threat. Accordingly, their political activity in free conditions was primarily oriented towards non-communist trends, such as achieving equality of rights, cultural autonomy or the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine. This was the case during a short period of democracy in Russia in 1917, in the Ukrainian People's Republic and in interwar Poland.

At the root of the Jewish communist stereotype lies the mystical belief that communism is not just a political choice, but a desire to take revenge on non-Jews (Christians). In communism, revenge is an innate feature rather than a historical context. The stereotype was partly rooted in the statistically greater presence of people of Jewish descent among the Soviet authorities and the Communist Party of Poland, which, however, never reflected the political preferences of the Jewish population as a whole. The high percentage of Jews among communists should be associated with their general higher level of social mobility and political activity. Historians point to various elements that stimulated this activity — both contextual and culturological. As an urban population with a tradition of respect for written culture, Jews had an easier access to education, which was the basis for social advancement. The expectation of a messiah who will bring the ultimate peace and justice to the Jews plays an important role in the Jewish religion. In its secular version, messianism is manifested in the support for ideas that guarantee the security of the Jewish population or declare that religious divisions do not matter: autonomy, Zionism, liberalism, socialism, communism.

Service in the Soviet government structures was possible for Jews only if they rejected their religious identity. However, non-Jews in the Communist Party did not accept them fully. They first allowed the creation of a Jewish section of the Communist Party and later exterminated Jewish leaders during the Great Terror. From that moment on, the presence of Jews in Soviet services was also insignificant in the territories of Western Ukraine. The Soviet government restored pre-war social restrictions on Jewish career opportunities. The authorities not only allowed but also compelled Jewish emancipation and public visibility, except for party structures or the People's Commissariat of Internal Affairs (NKVD). This emancipation did not, however, protect Jews from persecution. In the occupied territories, statistically, they were much more likely to be deported to Siberia than the rest of the population; besides, their religious life was repressed. The anti-Semitic nature of the Soviet Union became fully apparent only after World War II.

It was Nazi propaganda that took advantage of the vivid image of a Bolshevik Jew, supported it with evidence in the form of newsreels and photo chronicles, and turned the local non-Jewish population against the Jews.

During the September 1939 campaign, NKVD operative groups advanced through Western Ukraine simultaneously with the units of the Workers 'and Peasants' Red Army. Their top priorities included taking control of prisons and checking the prisoners they found there, seizing the archives of the Polish secret services, and arresting people they considered potentially hostile to the Soviet regime. The relevant instructions dated September 15, 1939, stated: “The NKVD operative groups must occupy premises that would meet the needs of the NKVD. They are to organize internal prisons to keep detainees in custody, providing security and service.” In Lviv, the so-called prison on (ul.) Łąckiego (ukr. Lontskoho) became such an internal prison, a building that previously housed the Polish police investigatory department and its pre-trial detention center. In fact, from the very first day of Soviet rule in the city, its cells began to be filled with new prisoners — members of legal and illegal political organizations, public activists, religious figures, regardless of their ethnic origin. As of September 28, 1939, 124 people were arrested in Lviv, including former Polish ministers Leon Kozlowski, Stanisław Grabski, Juliusz Tarnawa-Malczewski, one of the leaders of the Ukrainian National Democratic Union (UNDO), Volodymyr Tselevych, and others. On November 6, 1939, after the official incorporation of Western Ukraine into the Ukrainian SSR, the NKVD department for the Lviv region was established in Lviv, its investigatory department being housed in the building. In the course of investigative actions, physical and psychological pressure was actively applied to the prisoners. Olena Viter, a Greek Catholic nun, who was kept in the prison on Łąckiego in May 1941, recalled forced exposure and electric torture. Bohdan Kazanivsky, a member of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), who was also imprisoned there for some time, noted in his memoirs that "opinion about it [the prison] instilled fear in prisoners."

After the Third Reich's attack on the USSR, the NKVD was faced with the dilemma of what to do with overcrowded prisons in cities and towns under threat of rapid Nazi occupation. As a result, it was decided to release those arrested for domestic crimes and to shoot dead all political prisoners. In the prison on Łąckiego, the massacre began immediately, on the night of June 23-24, 1941. Only a few prisoners survived under the bodies of those killed. German researcher Kai Struve, after analyzing data on later exhumations, concludes that a total of 362 prisoners were shot in the prison on Łąckiego, actually all those kept there. Of these, 156 bodies were exhumed in July 1941 and another 206 in January-March 1942. Only a few of them were identified by relatives. The rest were buried in a mass grave at the Yanivsky Cemetery.

Nazi propaganda, after discovering the bodies of executed political prisoners, used this as an excuse to provoke attacks on the city's Jews. Newspaper publications were replete with accusations against the "Jewish Bolsheviks" at that time, effectively blaming the entire Jewish community for the crimes of the Soviet regime. The fact that Jews were also found among those shot dead was deliberately concealed. This was one of the reasons for an event known in the Holocaust historiography as the Lviv pogrom, in which about 200 Jews were killed; the number of those wounded, beaten, raped, and robbed cannot be established, but there certainly were thousands of them. In fact, the Lviv pogrom was a horrific mix of mass killings, public abuse, forced labour, and other manifestations of anti-Jewish violence that took place simultaneously in various locations of the city. The German military and the SS, members of the newly formed Ukrainian police, criminals, and ordinary Lviv residents of all ages, genders, and ethnic backgrounds — these were those to blame for all this.

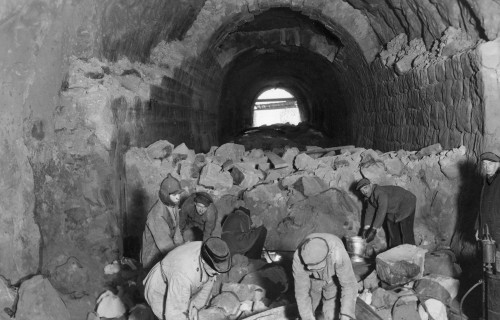

The prison on Łąckiego became one of the main centers of anti-Jewish violence during the Lviv pogrom. The events that took place in it and on the neighbouring streets were well documented, including photo and filming. On July 1, 1941, rioters drove there Jews from all over the city and detained them on the streets or in their own homes. Along the way, the Jews suffered physical and psychological violence. In the prison, they were forced to carry out the bodies of the executed political prisoners while they were repeatedly beaten hard. In January-March 1942, 24 Jewish bodies were exhumed in the prison. Most likely, these were victims of the Lviv pogrom.

During the subsequent period of Nazi occupation, there was a prison there, subordinate to the administrative department of the Commander of the Security Police and the SD in the District of Galicia (Kommandeur der Sicherheitspolizei und des SD im Distrikt Galizien), the main Nazi punitive body in the region. About 600 prisoners were constantly kept there — Jews and those who helped them, members of the anti-Nazi resistance and so on. From here they were deported to Nazi concentration camps or taken to the place of execution every Monday and Thursday. At the same time, the prison yard was repeatedly used as a gathering place for Jews before they were killed, for example, on July 25-26, 1941, during the so-called "Petliura Days", or in November-December 1941, during the "action under the bridge" as part of the forced relocation of Lviv Jews to the ghetto.

Some Jews were kept in the prison on Łąckiego for a long time because they were used as prison guards. For example, they were forced to pave the courtyard with matzevot from an old Jewish cemetery. The name of the Jewish prison doctor Leopold Bodek is also known. From October 26, 1941, Jewish skilled workers began to be kept there as they were forced to work for the needs of the security police and the SD. In July 1944, on the eve of the Red Army's entry into the city, most of them were shot dead in the prison yard; after the killing their bodies were taken away in an unknown direction. Some skilled workers were evacuated to Krakow with security and SD officers. In this perspective, one can speak of the prison on Łąckiego as the place where the Holocaust of Lviv Jews began and ended.

Immediately after the re-establishment of Soviet rule, prison cells began to be filled with real and imagined opponents of the regime. The NKVD (later the National Committee of State Security (NKGB), the Ministry of State Security (MGB), and the Committee of State Security (KGB)) Investigation Department and Detention Center were located there. In the 1960s and 1980s, well-known dissidents Vyacheslav Chornovil, brothers Mykhailo and Bohdan Horyn, Ivan Hel, and others were detained there.

The modern memorialization of the prison and the surrounding area is characterized by the marginalization of the memory of Nazi violence and the Holocaust in particular. Three memorial plaques have been placed on the building wall at different times. Two of them honour the memory of OUN members Mykhailyna Kyzymovych and Hryhoriy Holiash, who died there in the postwar period. The third contains the following inscription: "In memory of the victims of the NKVD-Gestapo-MGB, 1939-1953", which is actually mixing the prison’s Soviet and Nazi periods. In 1997, a monument to the Victims of Communist Crimes was unveiled on pl. Shashkevycha, opposite the former prison.

In 2009, the National Memorial Museum of the Victims of Occupation Regimes “Prison on Lontskoho” was opened in the former prison building, initially administered by the Security Service of Ukraine and transferred to the Ministry of Culture of Ukraine in 2011. The museum's exhibition focuses mainly on presenting the history of Soviet violence and Ukrainian nationalists as its victims. The history of the Holocaust and of the Nazi occupation regime in general is not actually presented. In view of this, the museum has repeatedly been criticised by both academic researchers and the media, which, however, has not so far caused the revision of its conceptual direction and thematic addition to the exhibition.