Vysoky Zamok Park (Lviv Castle Hill Park) ID: 22

Vysoky Zamok municipal park sits north of the city center, astride Lviv Castle Hill. Both park and hill take their name from the ruined fortress on the territory. Opened in 1835, the park’s landscaped hillsides are crisscrossed by a network of trails through lower and upper terraces. In the second half of the 19th century, an artificial mound was erected on the upper terrace as a marker of the Union of Lublin, and topped by a scenic viewpoint. A walkway beneath stands of ash and chestnut trees beautify the lower terrace.

Story

A vital step in the establishment of Lviv’s green space – or “emerald gown”, in the words of one scholar – was the creation in the 19th century of a park on the city’s highest point, Castle Hill, which skirts the basin where the city center is located. In the medieval and pre-modern periods, a castle stood on the hill, the so-called “high” castle, in contrast to the “low” castle that once stood on Kastrum Square near the Hetman Ramparts.

The original fortress occupied the hill already in the days of Danylo Halytskyi and his line. In time, a castle was added on the order of King Kazimir III, and the place came to be known as “Castle Hill”.

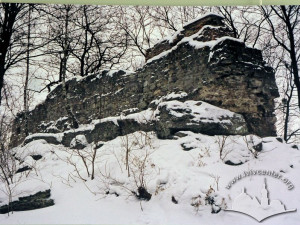

As defensive architecture, the high castle appeared in the era that predated the appearance of firearms. By the 17th and 18th centuries, it had become obsolete as a defensive structure, a fact that was borne home during its assault and capture in 1648 by the Cossacks under Bohdan Khmelnytskyi – and soon lost its military significance, falling into ruin. With time, the castle ruins were scavenged for building materials (Czołowski, 1910, 67–97; Krypyakevych, 1991, 21–25).

At the beginning of the 19th century, dry weather brought down a constant cloud of dust and sand from the castle ruins onto the city, and wet weather resulted in mudslides that cut deep gullies in the hillsides: “The falling water left gulches accessible only to cattle grazing or sunning themselves there.” The decision was reached to plant trees on the denuded peak and open a park on the old fortress site. The greenway was envisioned as a continuation of the gardens and promenades that had been established on the old city ramparts. Already by the decades of the 1820s and 1830s, picturesque, orderly pathways appeared, extensions of the recently established Governor’s Ramparts Park that flanked Castle Hill. Count Leopold Lazansky was a prominent and active supporter of the new park project. (Stankiewicz, 1928, 64–65).

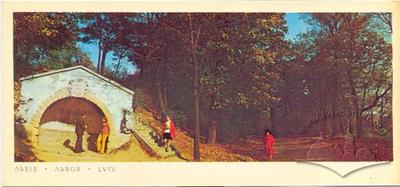

Trees and shrubs were planted on Castle Hill beginning in 1835, and most of the work was completed within a few years. The park’s quiet walks offered spectacular views of the city which lay in the valley below. An artificial grotto – complete with stone lions moved here from the old Lviv Town Hall – was constructed near the western slope (Czołowski, 1910, 99, 101). A park restaurant was opened in 1845 and, in 1868, a gardening center. Following the visit of Austrian Emperor in 1851, Castle Hill was given the official designation of “Franz Josefs Berg”.

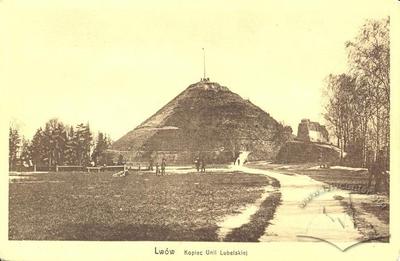

The final touch resulting in Castle Hill’s current topography and composition was the addition of a mound erected on the peak commemorating the 300th anniversary of the creation of a unified Polish-Lithuanian State - Kopiec Unii Lubielskiej. Work on the “historical landmark” was begun in 1869 under the direction of liberal politician Franciszek Jan Smolka (Czołowski, 1910, 102; Krypyakevych, 1991, 26). The mound certainly provides the hill its characteristic appearance, but has otherwise laid to rest any chance of research into the relevant strata of this singular archeological site (Czołowski, 1910, 107).

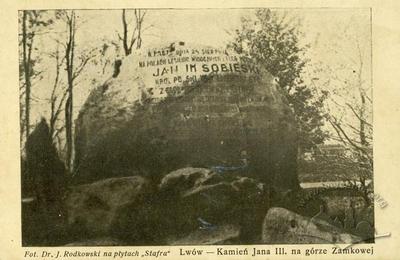

In 1883, on the northern, Pidzamche slope of the park’s lower terrace, a monument was laid commemorating Jan Sobiesky III’s victory in 1675 over the Tartar forces. And in 1948, not far from there on the greenway another memorial was placed, this one in honor of the victorious assault on the castle in 1648, led by Cossack colonel Maksym Kryvonos. For many years a stone lion stood near the Union of Lublin Mound. A gift to the city from the Lorencowic family, the lion has now been moved to the Museum of History.

In the 1950s the Lviv TV Tower was erected on the top of the hill with a television center nearby, the complex striking a discordant note in the overall landscaping of the park and hill.

At the start of the 20th century an electric tram traveled to the park, easing public access to the area. The line was later removed.

Architecture

Lviv’s Vysoky Zamok Park sits north of the city center on the heights of Castle Hill which – as the city’s highest point – both dominates the city skyline and skirts the basin of the city center. Alongside Lev Hill and several lower hills located to the east, Castle Hill marks the northwestern edge of the Volyn-Podilsk Uplands.

The territory of the park is marked off by the surrounding streets: Zamkova Street to the north runs parallel to the Pidzamche depot rail lines; Opryshkivska Street lies to the east and Vysoky Zamok Street to the south. On the west near the park boundary is the historic section of town, Old Market Square, in which Lviv’s oldest churches are concentrated. On the east, beyond Lev Hill, lies the Znesinnya Regional Park.

Castle Hill has two terraces: an upper and a lower. At the northern end of the lower terrace is the central walkway which loops the perimeter at the base of the upper terrace. One may visit two monuments here: the first commemorating King Jan Sobiesky’s victory over the Tartars, and the second, Maxim Krvyonosom’s capture of Castle Hill. On the southern side there is a scenic viewpoint, and on the west a gardening center, restaurant, and artificial grotto flanked by sculptures of lions moved here from the old Lviv Council building. According to Ivan Krypyakevych, the grotto stands atop the so-called Prince Hill which, as late as the 1830s, was a separate hill to the west of Castle Hill.

The top of the hill is accessible by winding staircases. Once there, one may visit the remains of the defensive structures of the High Castle, the 192-meter tall television tower, the television center, the artificial Union of Lublin Memorial mound, and the scenic viewpoint at 413 meters above sea level.

The composition of the leafy Castle Hill Park is reminiscent of the neo-romantic landscaped parks of Peter Josef Lenne at Potsdam.

Olena Stepaniv offers the following observation: “The park is comprised of two parts: the lower terrace with promenades and old-growth trees, and the upper, as it is called, glade.

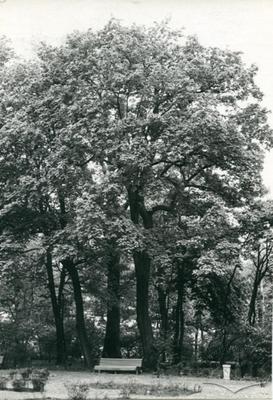

Park soil is made up of rubble and landfill, sand, and some scattered limestone deposits. Then thin deposit of arable soil is from decomposed organic matter over a long period. The trees in the park are predominately chestnut, maple, sycamore, ash, linden, birch, several varieties of poplar, acacia, and pine. Both the northern and southern faces of the hill are heavily forested.

The park main entrance is from the southeast, from Kryvonos Street. The southern entrance, from Zamkova Street, is less well-known. Many paths come from Pidzamche onto the heights”, (Stepaniv, 1992, 45).

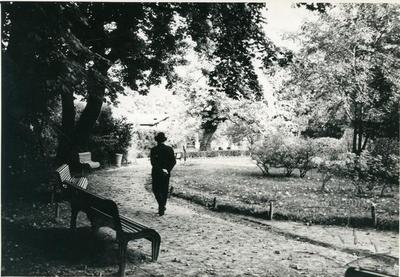

The lower terrace walkway under stands of ash and chestnut trees is a particularly charming section of the park.

At the close of the 19th century, the park territory was listed at 26.34 hectares (Miasto Lwów, 1896, 318–319). Currently, Castle Hill Park occupies 36.2 hectares.Related buildings and spaces

People

Maksym Kryvonos. Cossack colonel.

Ivan Krypyakevych. Historian.

Peter Joseph Lenné. Landscape architect, park designer.

Lorencowicz family. A local bourgeois family.

Franciszek Jan Smolka. Politician, civic activist.

Olena Stepaniv. Historian, geographer, civic activist.

Franz Joseph. Emperor of the Habsburg Dynasty.

Bohdan Khmelnytsky. Cossack Hetman.

Jan III Sobieski. King of Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Sources

- Ivanochko, U. et al. “Architecture of the late 18th and first half of the 19th Centuries,” Architecture of Lviv: Times and Styles, 13th-21st centuries, Biriulyov, Yuryi, ed. (Lviv: Center of Europe Publishing, 2008), 170-237

- Krypyakevych, Ivan. Historical Walks Around Lviv, (Lviv: Kamenyar, 1991)

- Stepaniv, Olena. Contemporary Lviv: A Guidebook, (Lviv: Phoenix, 1992)

- Barański, F. Przewodnik po Lwowie: Z planem i widokami Lwowa, (Lwów: 1902)

- Czołowski A. Wysoki Zamek: Z 19 rycinami w tekscie, (Lwów: 1910)

- Jaworski, F. Lwόw stary i wczorajszy (szkice i opowiadania): Z ilustracyami. Wydanie drugie poprawione, (Lwów: 1911)

- Kowalczuk, M. “Rozwόj terytoryalny miasta.” Miasto Lwów w okresie samorządu 1870–1895, (Lwów: 1896), 299–351

- Orłowicz, M. Ilustrowany przewodnik po Lwowie: Ze 102 ilustracjami i planem miasta, Wydanie drugie rozszerzone, (Lwów – Warszawa: Książnica-Atlas, 1925)

- Stankiewicz, Z. "Ogrody i plantacje miejskie," Lwów dawny i dzisiejszy: Praca zbiorowa pod redakcją B. Janusza, (Lwów: 1928), 62–71.

Citation

Ihor Zhuk. "Vysoky Zamok Park (Lviv Castle Hill Park)". Lviv Interactive (Center for Urban History, 2012). URL: https://lia.lvivcenter.org/en/objects/park-vysokyi-zamok/Urban Media Archive Materials