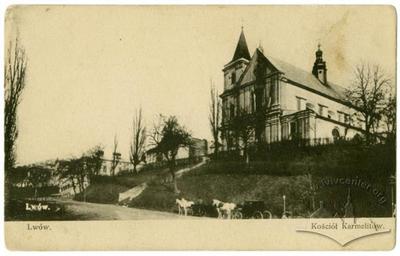

Vul. Vynnychenka, 22 – St. Michael Church (former church of discalced carmelites) ID: 185

The Church of the Discalced Carmelites with its monastery was a separate fortified point and was part of the city's overall fortification system. A monument of Baroque architecture in Lviv, it dates back to the first half of the 17th century (protected monument No. 374).

Story

The Carmelite Order appeared in Lviv in the 15th century. As early as 1443, the Carmelites of Ancient Observance, or Discalced Carmelites, had a wooden monastery and the Church of St. Leonard in the Halych suburb, founded by Krakow Castellan Jan Ligęza. This church was located near the house at vul. Kniazia Romana, 36 (Вуйцик, 2013, 308). After the monastery burned down during the siege by the Tatar troops, the Carmelites left the city. In 1444, the Church of the Epiphany was built on the site of the monastery.

The local population of the suburbs constantly opposed the monks, who had become a burden to them. The monks, in turn, constantly complained to the city authorities, who also treated them without much sympathy. In 1599, Lviv Archbishop Dymitr Solikowski renewed attempts to return the order to the city, but this was prevented by an epidemic and the death of the archbishop himself. The Carmelites arrived here at the beginning of the 17th century. According to one version, they received the land where the temple was later built from the suburbanite Voitykh Makukha in 1615. According to historian Ignacy Chodynicki, the monastery was built in 1614 with funds from Volhynian castellan Jan Łahodowski (Chodynicki, 1829, 384).

The first foundation of the Discalced Carmelite monastery, together with a wooden church, was located in another place, not far from the city walls in a marshy area. However, not wanting to live near the swamp that formed next to two rivers (the Pasika stream flowed into the Poltva here), the Carmelites appealed to the city authorities to allocate them a plot of land for a new monastery and funds to maintain their brickworks for the construction of monastery buildings and a church. Thus, in 1624, the magistrate granted permission to build a monastery in "Prussian masonry" (timber-frame). Such buildings were constructed as temporary structures: during sieges, they were destroyed so that they would not become a defense for the attackers. Therefore, in 1633, the Discalced Carmelites moved to the eastern part of the city, where they began to build the church and monastery that exist today on a hill opposite the Assumption Church. When establishing the complex here, the Carmelites counted on the future expansion of the city's fortifications and that their monastery would soon be within the city limits.

Construction of the church began in 1634 with the assistance of magnates Aleksander Zasławski, Aleksander Kuropatwa, Carmelite Adam Pokorowicz, son of Lviv builder of Italian origin Adam Pokora, known as de Burimo. The builder was probably Adam's brother, Jan Pokorowicz. Construction lasted from 1634 to 1641. Lviv jeweler Jakub Burnet donated 15,000 zlotys for the construction of a separate chapel next to the church, hoping to be buried in the church crypt (Łoziński, 1889, 92). On September 6, 1642, Carmelite fathers settled in the newly built monastery near the church, and the church was consecrated at the same time. From the very beginning, the monastery complex was fortified with high walls, which allowed it to defend itself during sieges.

Even after the church construction was completed, the townspeople did not attend it because it was located outside the city walls. There were only two gates through which one could leave the city — the Halych Gate and the Krakow Gate — but both were located far away. This forced the Carmelites to appeal to the king with a request to build a third gate in the city walls, opposite their church. The royal commission dealing with this matter (despite protests from the townspeople) determined in 1643 that the third gate would be located near the Assumption Church, which was named the Bosatska ("barefoot men's") Wicket (Зубрицький, 2002, 259).

In 1648, during the siege of Lviv, Bohdan Khmelnytskyi's troops occupied the monastery complex in just one day. The church was destroyed and stood without a roof for a long time. Thanks to Adam Kłosiński, who donated 70,000 zlotys for the restoration of the church, in the second half of the 17th century, the Carmelites rebuilt the church and monastery under the supervision of the royal engineer Jan Berens (Вуйцик, 1987, 70-71).

In September 1704, the fortified monastery of the Discalced Carmelites was captured by Swedish troops led by Charles XII. It was from the monastery of the Discalced Carmelites that the Swedes began shelling the city and organized an attack, capturing the city through the unlocked Bosatska Wicket. This marked the beginning of the gradual decline of Lviv's fortifications, which lasted until their complete destruction in 1777 (Вуйцик, 2013, 322). Notes indicate that during the Swedish attack, money that had been collected for the "church factory" was stolen from the monastery, from which we can conclude that the church was under construction at that time (Chodynicki, 1829, 245).

In 1717, the Carmelites managed to restore the church. In 1731–1732, Italian artist Giuseppe Pedretti, together with his Lviv student, monk Benedykt Mazurkewicz of the Bernardine monastery, painted frescoes on the walls and vaults. Hryhorii Chaikovskyi painted a scene from the history of the Carmelite Order. At that time, 12 side altars, an ambon, and wooden benches were also installed. As of 1759, only seven side altars remained in the church, dedicated to St. Joseph, Teresa of Ávila, Rosalia, John the Baptist, Simeon, Jesus Christ, and the Blessed Virgin Mary (Betlej, 2012, 135).

Starting in 1748, the Carmelites constantly competed with the Capuchins for parishioners. The clashes between the monks were accompanied by lawsuits and were a headache for the city authorities (Крип'якевич, 2007, 56-57). As a result of the Josephine Reform of 1781, the Capuchin order was liquidated, and in 1784 the Discalced Carmelites were relocated to a monastery in Zagórze, in southeastern Poland (now Sanok County, Subcarpathian Voivodeship). The monastery complex was transferred to the Reformed Order, but in 1789 it was given to the Discalced Carmelites.

In 1809, the Austrian authorities planned to turn the monastery into a military hospital and relocate the monks. However, resistance from parishioners postponed these plans for several years (Betlej, 2012, 135).

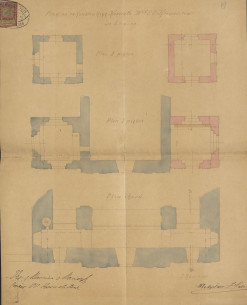

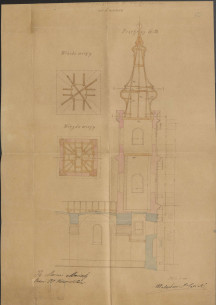

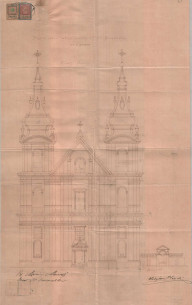

The church was not immediately completed in its present form. Engravings and lithographs from the 18th and first half of the 19th centuries depict the church without towers. The project for the construction of both towers in 1835-1839, which is kept in the Central State Historical Archive of Ukraine in Lviv, was carried out by architect Alois Wandruschka (ЦДІАЛ 742/1/1606). In the 1835 tower extension project, which was approved by the head of the construction department, Josef Markl, we see the north tower extended to the second tier, inside which the bell tower was located, while the south tower had only one tier. According to this project, the northern tower had a pyramidal top. The project was only partially implemented. In photographs from 1901-1906, only the northern tower is visible, as it is depicted in Wandruschka's project, while the southern tower remained at the level of the first tier.

In 1869, a monument to General Józef Dwernicki by Parys Filippi was installed in the church. In 1877, carved steelwork was installed in the presbytery according to a design by architect Władysław Halicki.

In 1906, the church was reconstructed according to a design by architect Władysław Halicki. At that time, the south tower was completed, both towers were given a Neobaroque finish, and the façade, bell tower, and interior altars and frescoes were completely restored (Вуйцик, 2013, 318).

In 1945, the Soviet authorities closed the monastery, and the monks left for Krakow. Homeless people began to settle in the monastery's empty premises. Later, the complex was converted into warehouses, which operated here until the 1970s. The monument to Józef Dwernicki was dismantled from the interior of the church and, after restoration in 2001, installed in the Latin Cathedral.

The monastery housed dormitories for the polygraphic technical school, as well as the KGB listening service. Since the early 1980s, part of the monastery building has housed separate departments of restoration workshops. In 1968–1982, the garden near the church became the site of the "Republic of the Holy Garden," where Lviv hippies and other informal groups gathered.

In the early 1980s, the Lviv Restoration Workshop (since 1990 — the Scientific and Restoration Institute "Ukrzakhidproektrestavratsiia") began engineering and restoration work on the heating and ventilation of the premises with the aim of adapting the monastery and church for use as a museum. The work was suspended due to resistance from the KGB, and the issue was only resolved in 1989. At the same time, the murals, defensive walls, and cellars were restored, and work was carried out to improve the grounds.

In 1990, Studite and Redemptorist priests, together with lay people, began to hold services at the entrance to the church. The vacated monastery premises were transferred to the Studite Order of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church. In 1992, the Publishing Department, better known as the Svichado Publishing House, began its work here and continues to operate to this day. The Institute of History of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church also operates at the monastery.

The Studite monks renovated the church and replaced the roof. Now the church is covered with copper sheeting. A stained-glass window has been installed above the choir loft, and four side altars have been added to the interior.

Architecture

The Discalced Carmelite Church of St. Michael the Archangel is oriented along a west-east axis and features an elongated rectangular plan, adjoined by a monastic cell building with an inner courtyard. Stone steps lead up to the main portal along the slope of the hill.

The monument is stone, three-nave, with a transept and massive supporting pillars in the interior. The building is covered with a gable roof featuring a ridge turret. In plan, it has the shape of an elongated rectangle. The façades are divided by pilasters with restrained architectural decoration; the windows are semicircular and feature surrounds.

Visually, the interior is perceived as a single nave with side chapels. The transept is covered with spherical vaults, the naves are semicircular with lunettes. The vaults are supported by pillars. The interior space of the side naves is formed by the interiors of the chapels. The width of the main nave is 10.0 m, and the side naves are 3.2 m wide. In the presbyterium, all three naves have domed ceilings, and in the sacristy, there is a groin vault. The monastery premises adjoin the eastern wall, so there is no traditional apse from the outside. The columns of the central nave are decorated with paired pilasters of the Corinthian order.

The main façade is divided by pilasters, flanked by two square towers with multi-tiered Neobaroque tops, between which a modest triangular pediment rises. The façade is simple, without excessive architectural decoration. It is enlivened by the strict rhythm of the vertical lines of the pilasters, which are restrained by the horizontals of the developed cornices of the second tier. The only sculptural decoration of the main façade is the figures of two saints in the niches of the first tier on either side of the main entrance.

Stylistically, it is a Baroque building, which, according to Bohdan Janusz, a researcher of Lviv's antiquities, is the first monument that broke with the Middle Ages and ushered in the true Baroque era in Lviv. The layout of this church is quite similar to that of the Jesuit church, although the buildings differ significantly in appearance.

The interior of the church is Baroque, but it is not as magnificent as the Bernardine or Jesuit churches. It contains valuable art treasures, including sculptures and paintings from the 17th to 18th centuries, with additions made in the 19th century.

The church is decorated with a large tempietto altar made of black and red marble, attributed to the 17th-century Lviv sculptor Oleksandr Prokhenkovych, a student of Jan Pfister. This is the only artistic monument dating back to the time of the church's construction. Their author was the Italian artist Giuseppe Pedretti. The altars of the north and south naves — Christ and St. Tadeusz — date back to the 18th-19th centuries, and their sculptures have been partially preserved. Today, they stand against the eastern wall of the church. The carpentry work on these altars was done by Ivan Bocharskyi. The images on the altars were painted by Hryhorii Chaikovskyi (1709-1757), who was a monk at this monastery. Chaikovskyi received his artistic and medical education in Rome. The church also housed several portraits of his work. There was also one canvas ("Lamentation") by Martino Altamonte. The frescoes were repainted during later restorations.

In addition to the altars, the church has a monument to General Dwernicki by Parys Filippi (1869), a black marble memorial plaque with a portrait of Peter Branicki (1762), a monument to Borkowski-Dunin, and a commemorative plaque to Felicja Boberska by Stanisław Roman Lewandowski.

Currently, only the frescoes, tombstones, and epitaphs from the 19th century remain from the interior decoration. The altars are damaged, and the paintings and sculptures have been lost. The altar of the northern nave near the presbyterium has partially preserved wooden sculptures, in particular, the figure of a flying angel by Lviv sculptor A. Shtyl from the first half of the 18th century.

The territory of the Carmelite complex and its surroundings is enclosed by Vynnychenka, Lysenka, and Prosvity Streets and a square off Korolenka Street. Fragments of the defensive wall have been preserved on the side of Prosvity Street with coats of arms and an inscription referring to King Jan Sobieski. As an accompaniment to the Carmelite church, not far from it on the north side, there is a church and monastery of the Discalced Carmelites.

People

Leszek Allerhand (1931-2018) — was a physician and grandson of the renowned Lviv lawyer Maurycy Allerhand. Together with his parents, he survived the Holocaust in Lviv.

Jan Berens — royal engineer. He designed the fourth and fifth lines of Lviv's defensive bastion fortifications, known as the "Berens Line."

Piotr Bronicki — Polish nobleman.

Jakub Burnet — a Lviv jeweler who donated 15,000 zlotys for the reconstruction of the temple, hoping to be buried there.

Alois Wandruschka — a Lviv architect.

Władysław Halicki — architect from Lviv

Józef Dwernicki — Polish general, whose monument was located in the church.

Aleksander Zasławski — voivode of Bratslav and Kyiv, bearer of the Baklai coat of arms. Founder of the monastery and church of the Discalced Carmelites.

Adam Kłosiński — donated funds for the reconstruction of the church after the attack by B. Khmelnytskyi troops.

Aleksander Kuropatwa — representative of the Polish noble family, coat of arms Yastrebetz. Founder of the church.

Myroslav Ivan Lubachivsky — Supreme Archbishop of Lviv of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, Cardinal of the Catholic Church.

Jan Łahodowski — founder of the Discalced Carmelite church.

Benedykt Mazurkewicz — Benedictine monk, painted the interior of the church.

Voitykh Makukha — Lviv suburbanite who donated his garden for the construction of a church and monastery there.

Giuseppe Carlo Pedretti — Italian artist. He painted the church.

Adam Pokora de Burimo — Lviv builder of Italian origin.

Jan Pokorowicz — Lviv architect and builder.

Dymitr Solikowski — Latin archbishop of Lviv.

Jakub Sobieski — representative of the noble Sobieski family, coat of arms of Janina, father of King Jan III Sobieski, founder of the church and monastery of the Discalced Carmelites.

Parys Filippi — Lviv sculptor. Created a sculpture of General Dwernicki.

Hryhorii Chaikovskyi — Lviv artist. Painted the interior of the shrine.

Anton Shtyl — Lviv sculptor, student and follower of Georg Pinsel. He decorated the altar of the Discalced Carmelite Church.

Elżbieta Jaćmierska — founder of the Discalced Carmelite Church.

Sources

- Науково-технічний архів інституту "Укрзахідпроектреставрація". Акт техстану. Технологія і методологія, фотофіксація, Л-2-1, 1965.

- Науково-технічний архів інституту "Укрзахідпроектреставрація". Паспортизація. Т. І, Л.2-3, 1974.

- Науково-технічний архів інституту "Укрзахідпроектреставрація". Історична довідка Т. ІІІ. Л.2-2. 1975.

- Науково-технічний архів інституту "Укрзахідпроектреставрація". Проект благоустрою території Т. VI. 1976. Л. 2-7.

- Науково-технічний архів інституту "Укрзахідпроектреставрація". Проект реставрації оборонних стін Т.VII. 1976. Л. 2-8.

- Науково-технічний архів інституту "Укрзахідпроектреставрація". Облікова паспортизація на художні твори що збереглися в пам’ятці архітектури. 1993. Л.238-3.

- Іван Банах, Хіппі у Львові, (Львів: Апріорі, 2015), Вип. 3, 135-139.

- Володимир Вуйцик, Leopolitana, (Львів: ВНТЛ- Класика, 2013), 308–323.

- Бартоломей Зіморович, Потрійний Львів (Львів: Центр Європи, 2002).

- Денис Зубрицький, Хроніка міста Львова, (Львів: Центр Європи, 2002), 259.

- Володимир Вуйцик, Роман Липка, Зустріч зі Львовом, (Львів: Каменяр, 1987), 70-71.

- Памятники градостраительства и архитектуры Украинской ССР, (Київ: Будівельник, 1986), Т. 3, 78.

- Юрій Смірнов, "Храм Святого Архістратига Михаїла (колишній костел кармелітів босих)", Галицька брама, 2011, №5-6, 30-37.

- Ігор Сьомочкін, "До історії Босяцької фіртки Львівських фортифікацій", Вісник інституту "Укрзахідпроектреставрація", 2007, №17, 5-14.

- Іван Крип'якевич, Історичні проходи по Львові, (Львів: Центр Європи, 2007), 56-57.

- Andrzej Betlej, "Kościół P. W. Św. Michala Archanioła i klasztore OO. Karmelitów Trzewiczkowych. (Pierwotnie OO. Karmeletów Bosych.)", Materiały do Dziejów sztuki sakralnej na ziemiach wschodnich. Kościoły i klasztory rzymskokatolickie dawnego województwa ruskiego, T.20, Kraków, 2012, 133-163.

- Ignacy Chodynicki, Historya stołecznego królestw Galicyi i Lodomeryi miasta Lwowa: od założenia jego aż do czasów teraznieyszych, ( Lwów: Nakład Karóla Bogusława Pfaffa, 1829), 245.

- Władysław Łoziński, Złotnictwo lwowskie w dawnych wiekach: 1384-1640, (Lwów: Gubrynowicz i Schmidt, 1889), 92.

- Tadeusz Mańkowski, Lwowskie kościoły barokowe, (Lwów: Nakładem towarzystwa naykowego, 1932), 41–48.

- Mieczysław Orłowicz, Ilustrowany przewodnik po Lwowie ze 102 ilustracjami i planem miasta, (Lwów-Warszawa, 1925), 180.

Citation

Andrii Husak. "Vul. Vynnychenka, 22 – St. Michael Church (former church of discalced carmelites)". Lviv Interactive (Center for Urban History, 2018). URL: https://lia.lvivcenter.org/en/objects/st-michael-church/Urban Media Archive Materials