The Lviv rally against celibacy ID: 89

The largest scale protest action against the introduction of celibacy in the Greek Catholic Church took place on Markijana Szaszkiewicza str. in the premises of the Mykola Lysenko Music Society on February 8, 1925.

Story

After the disintegration of Austria-Hungary and joining the Polish state, Lviv lost its status as the capital of a large province and began to play the role of just one of the peripheral centers in Polish socio-political life, much inferior to Warsaw and a number of other cities. For the Ukrainian population of Galicia, the city remained both a symbolic and organizational center, where the headquarters of political parties, scientific, cultural and economic institutions and the editorial boards of most periodicals were concentrated. Most importantly, Lviv continued to be the core of the Galician metropolitanate of the Greek Catholic Church, which was a most important component of Ukrainian identity in the region, whose fate was considered not only a purely ecclesiastical but also a national matter.The rally ("viche") against the introduction of compulsory celibacy for the Greek Catholic clergy became a good illustration of the city's importance for Ukrainian political and ecclesiastical life. It was triggered by the decision of Yosafat Kotsylovskyi, the Bishop of Przemyśl, to ordain to the priesthood only those graduates of the Theological Seminary in Przemyśl who agreed to become celibates. Earlier, in 1920, a similar step was taken by the greatest enthusiast for the introduction of celibacy for the Greek Catholic clergy, Bishop Hryhoriy Khomyshyn of Stanisławów. The position of Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky remained unclear, although most clergy and secular figures suspected him of similar intentions.

Although the idea of celibacy had some rational basis: the difficulty for priests to keep their families in the economic crisis, celibates' being less dependent on secular power, strengthening discipline, focusing on spiritual rather than political matters, etc., the vast majority of Galician Ukrainians, both laypersons and clerics, perceived it very negatively. This position is best explained by the course and resolutions of the rally held on February 8, 1925.

To prepare it, a "Committee for the Defense of Church and People's Affairs" was established in Lviv, headed by 83-year-old Yulian Romanchuk, a former member of the Galician Sejm and Austrian parliament (where he was vice president of the House of Deputies for some time) and a leading populist movement figure from the 1870s. Oleksandr Barvinskyi and representatives of the clergy, Oleksandr Stefanovych and Havryil Kostelnyk, also played an important role in the committee. The preparation of the rally became a task for the Ukrainian National Labour Party (UNTP) milieu, as the committee members decided not to involve radicals, socialists, and Russophiles, the latter because of their pro-government policies. The degree of dissatisfaction with the episcopate's actions is evidenced by the fact that at a meeting of the committee Havryil Kostelnyk called them an "anarchic arbitrariness." Initially, it was planned that Fr. Yaroslav Levytskyi would deliver the keynote speech, but the draft he proposed seemed too radical for the most committee members. Therefore, the mission was entrusted to Bohdan Barvinskyi, considered to be more moderate. After completing the preparations, the committee sent a request to the Lviv Police Directorate to hold a meeting in the large hall of the Mykola Lysenko Music Society on Szaszkiewicza 5 str. (now Shashkevycha square). The police response was positive.

The chosen location for the rally draws attention to several important aspects. The fact that it took place indoors was traditional for the political life of that time, though, considering the number of participants (about two thousand people, according to the newspaper "Dilo"), there may have been need for some open space too. However, the traditional space for Ukrainian demonstrations — the square in front of St. George's Cathedral — was not suitable this time. The rally was being prepared as a public protest against the actions of Greek Catholic hierarchs, including Metropolitan Sheptytsky. Even the meetings of the preparatory committee showed that its tone would be too sharp to sound directly in the heart of the Galician metropolitanate. Another fact is that Szaszkiewicza str. was at that time one of just a few streets in Lviv named after a Ukrainian figure.

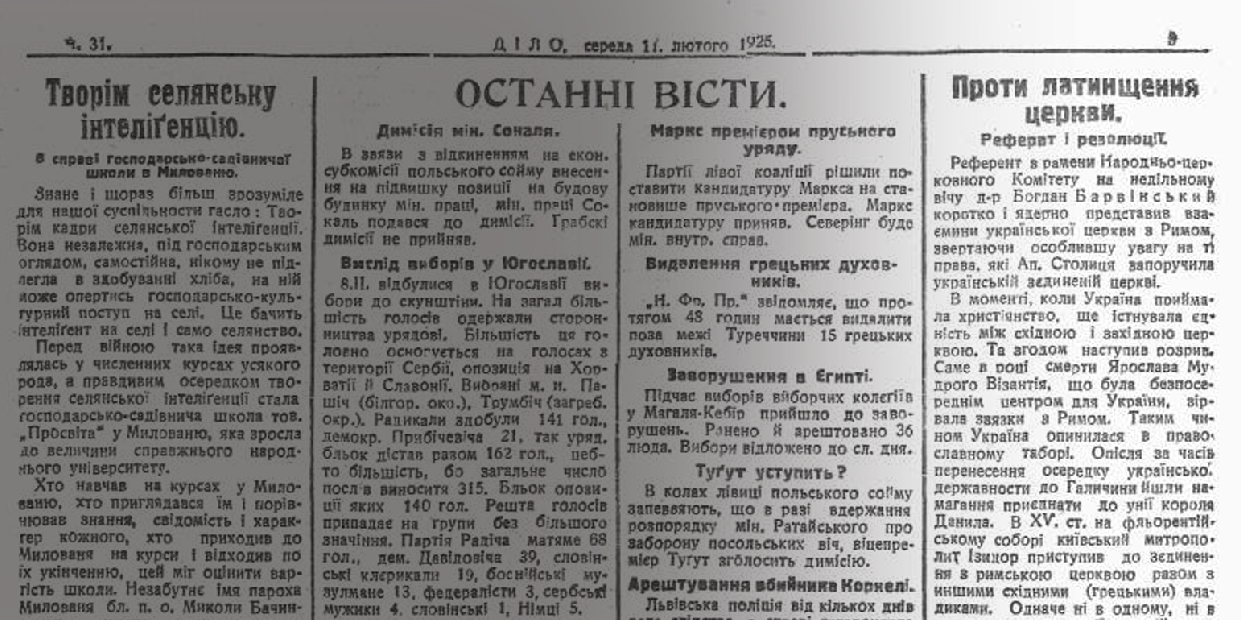

On Sunday, February 8, 1925, at 12:15, the rally was inaugurated by Yulian Romanchuk. The event was based on a speech by Bohdan Barvinskyi, who, according to a journalist of the "Dilo", "briefly and nuclearly" described the history of the Brest Union and the future of relations between Rome and the Greek Catholic Church. The speaker's main thesis was the impossibility of introducing celibacy, because it was contrary to the historical tradition of the church and violated the rights guaranteed to it by Rome. Criticizing the metropolitan and the bishops, Barvinskyi blamed an "invisible hand" for trying to "Latinize" the Greek Catholic Church, meaning Poles and those circles in Rome who wanted to unify the Greek Catholic rite with the Roman Catholic one. Those present greeted the speech with applause.

Bohdan Barvinsky's speech electrified the already categorical audience, this being reflected in the resolutions of the rally. The intention to introduce celibacy was proclaimed as leading to the destruction of the union, the Greek Catholic Church, and the entire Ukrainian people, while the hierarchs' actions were declared arbitrary and unlawful. The historical merits of the married (white) clergy for the Ukrainian society were specially emphasized, particularly in the creation and education of the secular intelligentsia. It was decided to establish eparchial church-and-people's committees (in Przemyśl, Stanisławów and the Central Committee in Lviv) and to prepare an appeal to Pope Pius XI to protest against celibacy.

The one-sidedness, rigidity and pathos of the rally clearly demonstrate a number of important things. The tone of the event reflected the general mood of Ukrainian society in a situation when students of Theological Seminaries in Przemyśl and Stanisławów went on strike against celibacy (and encouraged their Lviv colleagues to join them), the Ukrainian press often using blatant curses at bishops. This shows that St. George's Hill in Lviv not only ceased to be in the lead of Galician Ukrainian policies, as it was during the second half of the 19th century, but in fact became, like the whole Church, a political instrument in secular hands. Even purely ecclesiastical affairs were now evaluated primarily in terms of "national interests." At the same time, the rally's resistance to the idea of celibacy was often based on irrelevant ideas and testified to the reluctance of Galician Ukrainians, including Lviv residents, to recognize the post-war status quo. First of all, in the new conditions the role of married clergy had significantly decreased compared to the Habsburg era for a number of reasons: the wartime hardships, the growth of secular intelligentsia, the spread of new, often anti-church ideas, the unfavourable (unlike the Habsburg times) attitude of the government.

The event's radical disposition influenced Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky's decision not to imitate the actions of other bishops. However, despite the painstaking preparation and a significant number of participants, the Lviv anti-celibacy rally did not cause a significant resonance. With the exception of the "Dilo" and some other UNTP-related periodicals, the Lviv Ukrainian and Polish press ignored it. What is important is the "silence" of the Russophiles, who were also extremely hostile to the idea of celibacy. Nevertheless, political differences caused them to cover only their own anti-celibacy events. Anyway, the biggest obstacle to the resonance of the rally distracting the public from the celibacy issue was the signing of the Concordat between Rome and Poland, which took place a few days later. After all, this document did not satisfy the interests of the Greek Catholic Church, limiting its territorial jurisdiction and making it significantly dependent on the Polish state. So the Ukrainian society had a new, more relevant reason for protests.

Sources

- Львівська національна наукова бібліотека ім. Василя Стефаника, відділ рукописів, фонд 159 (Глинські), справа 51 (Барвінський Олександр. Листи до Глинського Ісидора, 1924-1926);

- Центральний державний історичний архів України, м. Львів, фонд 309, опис 1 (Наукове товариство ім. Шевченка, м. Львів), справа 2574 (Матеріали про проведення народних зібрань у Львові, Станіславові і Коломиї щодо збереження церковної унії, 1925);

- "Проти латинщення церкви", Діло, 1925, Nr. 30, 31;

- Роман Лехнюк, На порозі модерного світу: українські консервативні середовища в Галичині в першій чверті ХХ століття (Львів: Літопис, 2019).