Rynok Square in Lviv

Market Square is among the most ancient and most fascinating areas of Lviv – the vital core of urban life from the Middle Ages to the current day. The Square began to take shape as the center of this “walled city” in the 13th and 14th centuries, planned in accordance with the principles of the Magdeburg Rights. The structural ensemble which currently encircles the Square took shape over centuries, preserving elements and aspects of a variety of styles and epochs. Its appearance was influenced by pan-European architectural trends, urban trends, and the aesthetics of the various ethnic groups which have inhabited Lviv. Each building which stands on Lviv’s Market Square has been designated a Ukrainian National Historic Architectural Monument. The designation of Lviv’s central Market Square as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1998 stands as further testimony to its singularity.

The date of Lviv’s founding is a subject for debate. It is established that the first settlements of the city were located on the slopes of Zamkovy Hory, or Castle Hill, near the Royal Castle. Today Lviv’s oldest churches can be found there: St. Mykola Church, St. Paraskeva Church, the St. Onuphria Monastery, and the Church of John the Baptist. At that time the center of Lviv was the square which currently goes by the name Staryi Rynok, or the Old Market.

During the 13th and 14th centuries Lviv was afforded the right to self-governance, the Magdeburg Rights. The privilege afforded city residents more than just liberal exemption from central government rule, it also greatly influenced the city structure, through the establishment of a new, so-called “designated” city with an organized network of streets and fortifications encompassing it. This new ‘center’ was located to the south, near the ancient road to Halych, the capital of Galicia at the time. In the center of ‘designated’ Lviv appeared a quadrangular, nearly square market plaza, ringed on all four sides by residential buildings. At the center stood the “Rat”, or Town Hall, the home of Lviv government. The town’s central church – the Roman Catholic Cathedral – was located near the square. This configuration was typical in all cities of East Central European of the day to which Magdeburg Rights had been extended.

Lviv had long been a crucial trading city and Market Square the place where that trade was concentrated. Marcin Gruneweg, author of the earliest written account of Lviv (mid-16th century) was duly taken in by the city’s impressive appearance and prosperity, noting that one could purchase a limitless variety of goods, both local and imported, and encounter buyers from every country of the world.

In addition to serving as a market, Market Square was also the center civil government, and the social and spiritual life of town residents. It was a place where a wide variety of events were held, including celebrations of victorious military campaigns, religious observances, and much more. Here also, on the west end of the square near the city council building was the pillory (Polish, pręgierz) where corporal and capital punishments were carried out. It was at this place where, in 1578, the legendary Cossack Hetman Ivan Pidkova was executed.

The city council building was home to more than just the city council, it also headquartered the treasury, the court, the city guard, the city jail, and various shops among others. An obligatory feature of this type of structure was a clock tower which was placed to stand out in the city skyline in order to show from afar the location of the market square. Yet, it also served other functions. In time of fire or the approach of an enemy force, the town trumpeter would signal a warning for town residents. In later periods a bell was used to sound the alarm.

In Lviv, as in many other cities of its type, the council building was not the only structure at the center of its market square; as late as the 19th century, three rows of stone manor homes stood here as well. Together with the council building they formed what was known as the market’s “central block”.

Around the square in the market’s “outer blocks”, stood homes belonging to the wealthiest residents, the patrician class, made up chiefly of merchants and financiers who ran the city council and vital municipal establishments, and who had significant financial, political, and legal influence. Their stone manor houses, correspondingly, reflected the high status of their owners and set the standard for city residential buildings.

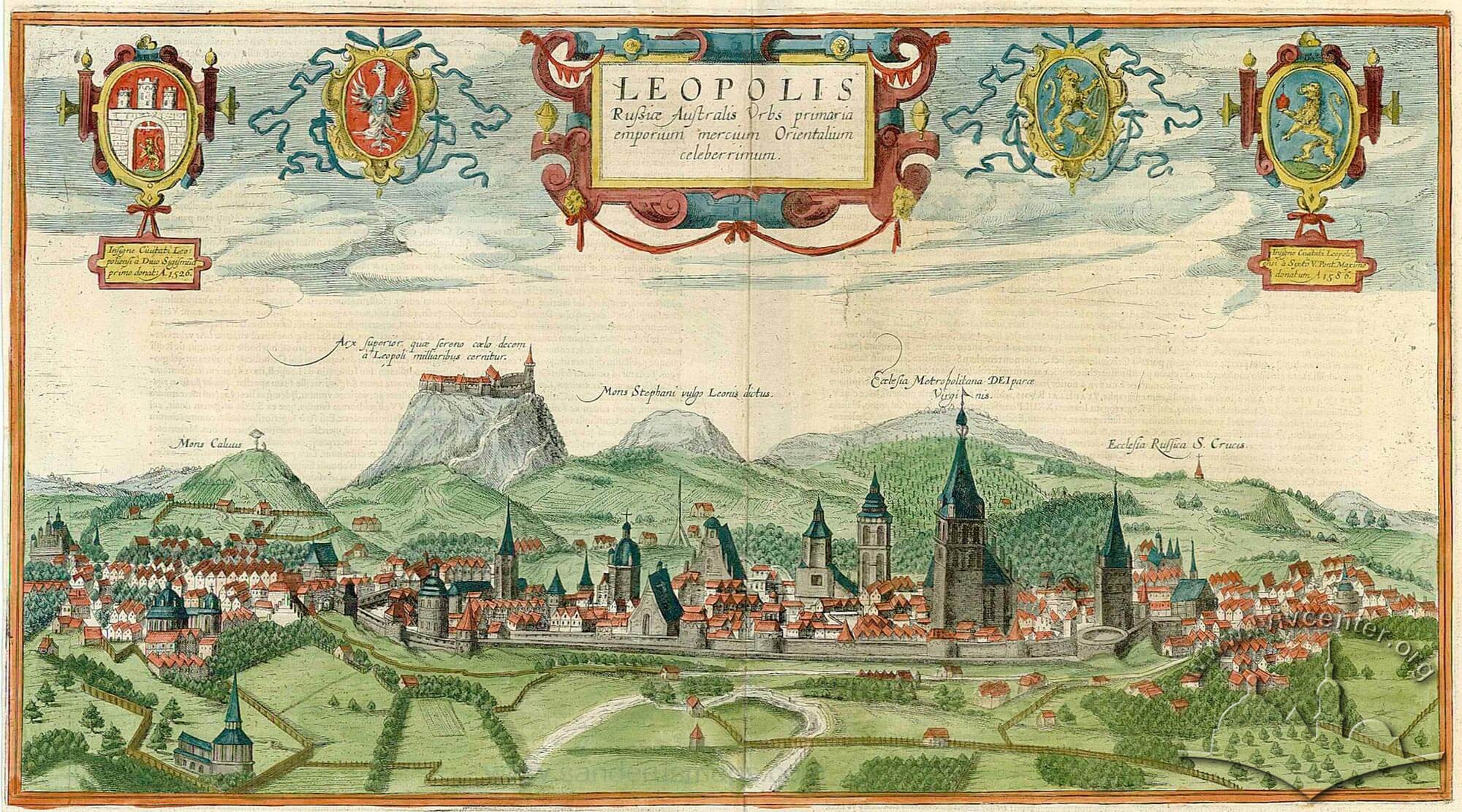

The architectural ‘face’ of Lviv’s Market Square has undergone repeated alterations over time. Medieval (gothic) Lviv architecture was composed primarily of “Prussian Masonry” homes of timber frame and brick, with a steep pitched wooden shingled roof which overhung the façade. Unlike the current appearance of the buildings on the square, at that time buildings were not constructed to form a seamless line along the façade, but were staggered and often with passages running between them. This type of construction can be seen in the Hohenberg engraving illustrated below:

In addition, these homes situated near the market had a kind of “open gallery” or stalls (Ukrainian, pidsinnya) which ran along the perimeter of the square. Similar market arrangements are visible in cities throughout Europe. In Lviv these galleries were wooden, and have not been preserved.

In 1527 nearly the entirety of Lviv was lost in a great fire. The subsequent, renaissance-era renovation of the city arose from its gothic-era foundation, but calling for entirely stone construction inasmuch as the magistrate had entirely prohibited wooden construction. Surviving gothic elements were incorporated into the new structures and are visible to this day in the facades of the brick manor homes at Market Square #16, #26, #44, and #45. At #18 and #28 intriguing examples of late-gothic portal framing construction has been preserved.

This Renaissance trend led to the arrival in Lviv of Italian master craftsmen and architects; commissioned by the city’s wealthiest residents, they oversaw the construction of their new homes. And yet the Lviv Renaissance is no mere facsimile of the Italian style, but represents a clean fusion with local construction tendencies and traditions. Thus frequently a Renaissance façade – as at #6, the Kornyakta Manor, (see photo) – conceals an interior strongly reminiscent of the Gothic: ribbed vaults on the ground floor, with the framing and ribs characteristically finished in white rough stone detail. The characteristic feature that distinguishes this style is the asymmetrical composition of the façade. If a façade was tri-windowed, two windows would be place nearer to one another with the third at a bit of a remove. Other elements include rusticated stone of a type visible in the faceted stonework of the “Black” and “Venetian” Manors (#4 and #14, respectively), and attics which “crown” the structures (#4, #6), in both form and function.

The greater part of the construction on Lviv’s Market Square was completed during the 16th and 17th centuries. Yet with new homeowners and changes in taste came changes in architectural style. A number of Manors were torn down and others rebuilt in their place, some with redone, vivid facades and interiors. One particularly excellent architectural Baroque specimen on Rynok Square is Manor #10 – the former palace of the House of Lyubomyrskyi. Another is the rebuilt Renaissance building refashioned in Baroque style at #33.

At the close of the 18th century with the arrival of Austrian rule in Galicia, Lviv underwent a significant transformation. The dismantling of the town fortifications altered the fortified, medieval character of the city for good. Numerous municipal functions were shifted outside the city limits, in particular cemeteries, which had traditionally been located near churches, a practice especially true of Roman Catholic churches. A park zone replaced the ramparts and trenches, and soon became a popular spot for an evening stroll among Lvivites. In time, a new city center would be formed around the current Prospect Svobody, with well-ordered structures including theaters, hotels, banks, and other civic buildings. A similar approach, though much larger in scale, was followed during the subsequent construction of Vienna’s Ringstrasse.

At the start of the 19th century, four ancient springs on Rynok Square were converted into fountains topped with neo-classical statues of Greek and Roman deities: Neptune, Amphitrite, Adonis, and Diana. The noted sculptor Hartman Witwer is most likely the author of these works.

An important date in the history of Lviv’s Rynok Square is 1826, the year when fire destroyed the ancient City Hall. In order to make room for the new large-scale structure, the entire medieval section of the square was razed. A new City Hall built on an impressive scale and style had long occupied the thoughts of the city’s foreign bourgeois class; a structure that would testify to Austrian Empire rule in Galicia. The fire necessitated the large-scale reconstruction of the square, a project which defines the character of Rynok Square to this day. The square was leveled, new cobblestone laid, and a new order established. Many manor homes were rebuilt in Neoclassical and late-Empire style with four stories (#2, #9, et al.). The final marked change to the appearance of the square came with the construction of new manors at #11 and #32 in the early-20th century. #32 (its alternate address is 2 Shevska Street) was the UniverMag Department Store which went up in 1912. Although the structure manifests stylized elements and architectural motifs typical of the Renaissance – an attic, garlanded and corniced windows, rusticated stonework – the structure is the most recent construction on Rynok Square.

As of this writing, the majority of the brick manor homes on Rynok Square have retained their residential function, though several have been converted into museums (#2, #4, #6, #24), hostels (#3), and others offices, a library (#9), stores, cafés, and restaurants. The City Hall and has served and will continue to serve as the home of the City Council. Visitors to Lviv and residents alike spend their free time on Rynok Square, drawn by the spirit of the Old Town, the historic neighborhood and its architectural treasury, its museums, and its modern establishments alike. Here – in particular during the summer season – concerts, festivals, civic activities, and open air exhibitions are a constant feature of Rynok Square, bearing witness to its role as the crucial center of urban life in Lviv. A space that is able to adapt to every new demand placed upon it, and yet a space that to a vital degree, ever will remain unchanged.

by Olha Zarechnyuk

Yulia Pavlyshyn, editor