House of Solomiya Krushelnytska ID: 253

Short biography of Solomiya Krushelnytska. Acquisition of Krushelnytska's property by the Soviet authorities: nationalized house and forced sale of the villa in Italy with a small monetary compensation.This story is a part of the theme about Soviet Occupation in 1939-1941, prepared as a part of the program The Complicated Pages of Common History: Telling About World War II in Lviv.

Story

In 1903, Solomiya Krushelnytska bought a house on ul. Kraszewskiego 23. At the time of the acquisition of the house, the singer was at the zenith of her fame: she had already performed at La Scala and got applause in Krakow and Warsaw; a tour to Odessa and St. Petersburg was behind while the triumphant role of Madame Butterfly in the opera of Puccini, complicated parts in the works of Wagner and Strauss, as well as touring beyond the ocean were still ahead. Anyway, almost every year Solomiya Krushelnytska came on holiday to Galicia.In September 1939 the singer was on holiday in the Carpathians, in the village of Dubyna near the town of Skole. She did not directly witness the entry of the Soviet army into Lviv and the first weeks of the occupation. Krushelnytska managed to get to her house (ul. Kraszewskiego 23) only a month after the Soviet troops entered Lviv; in late November 1939 she ceased to be the owner of this townhouse: at the request of the Soviet administration, Krushelnytska was forced to sign the nationalization act in the presence of her niece, Osypa Bandrovska, and the then administrator of the house, Yulian Drozdovsky. Of the entire house, the artist had only four rooms left, where she lived with her sister Hanna for the rest of her life.

Since Solomiya Krushelnytska was an Italian citizen at the beginning of World War II, the question arose as to why the singer did not leave Soviet Ukraine. Solomiya Krushelnytska did not keep a diary. For public, her work was as open as her private life was closed.

It was in this house that the singer lived through the Nazi occupation and the return of Soviet rule. Despite her decision to stay, she had problems with obtaining Soviet citizenship and until 25 September 1948 she was a citizen of Italy; after the formalities with citizenship were settled, she lost all property rights in Italy. Krushelnytska’s villa in Viareggio was sold by the Soviet embassy through a lawyer in Rome, Solomiya Krushelnytska receiving a small monetary compensation.

In Ukrainian historiography, Solomiya Krushelnytska has been made an idealized image of a Ukrainian woman through which her very interesting, complex and extraordinary life cannot be seen properly. Many questions remain without answers, especially those concerning the Soviet period. Krushelnytska was not arrested; instead, she was with great difficulty allowed to work at the conservatory. Her name was not as well known and present in public space as the names of her colleagues Filaret Kolessa, Stanislav Liudkevych and others.

Sources

- Оля Гнатюк, Відвага і страх (Київ: Дух і Літера, 2015), 496.

- Галина Тихобаєва, Ірина Криворучка, Соломія Крушельницька: Міста і слава (Львів: Апріорі, 2009), 167.

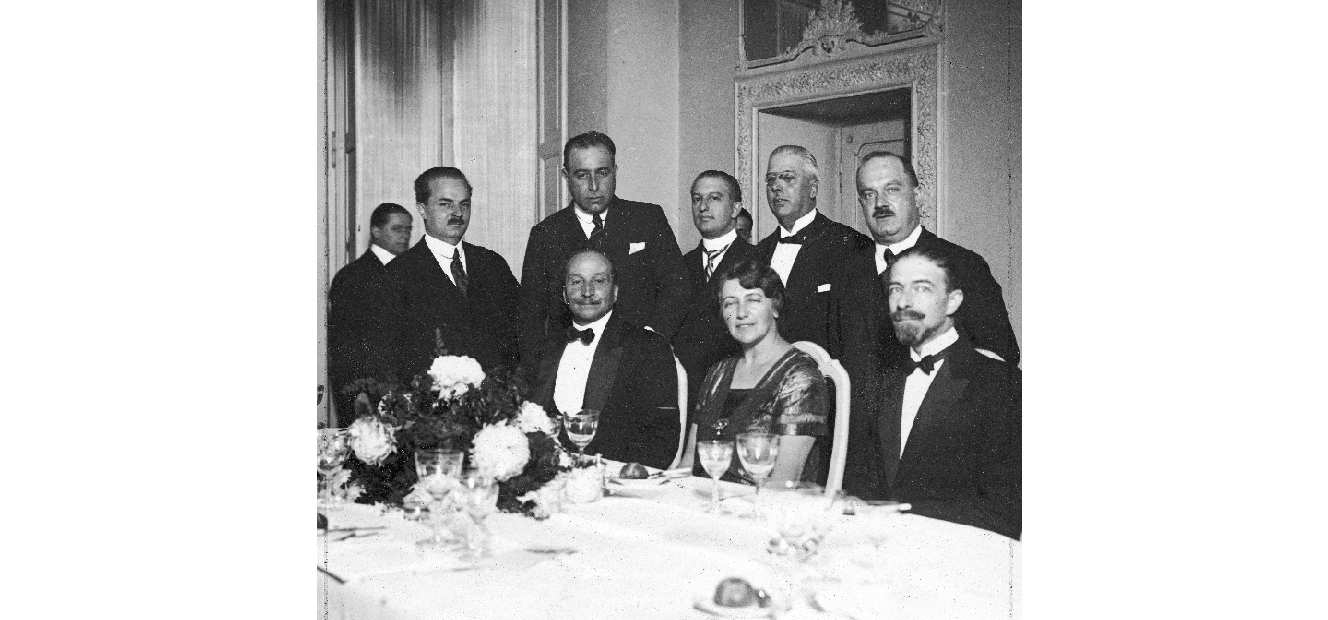

Cover photo: Solomiya Krushelnytska in Rome at the reception hosted by Prince Giovalli after her performance at the Royal Philharmonic, 1924. Source: from the collection of National Digital Archives of Poland (NAC, 1-K-8381).