Stryiskyi Park ID: 20

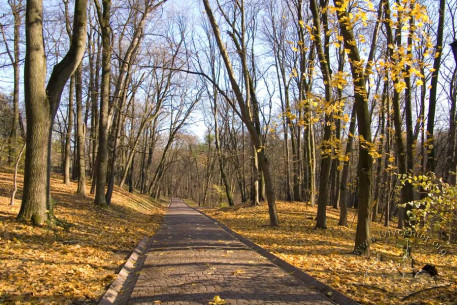

Stryiskyi Park sits in south Lviv between Stryiska Street and the upper part of Franko Street, on a ridge where Soroka Creek had its source. Arnold Röhring – the esteemed “park inspector” of the majestic capital city of Lviv – was the architect in charge of the design of this celebrated park. Work on the territory was begun in 1887. The design of the lower terrace reflects the landscaped pleasure garden approach, while the upper terrace, equipped to host the 1894 regional Expo has a more formal structure. In Stryiskyi Park’s more than 50 hectares of woods grow maple, chestnut, alder, birch, beech, oak, sycamore, acacia, linden, pine, and other varieties of trees.

Story

Stryiskyi Park in Lviv was founded on land that marked the early southern outskirts of the city known as Stryi, which was near an ancient cemetery that closed in 1823. The lot for the new park had been a section measuring 70 Frankish (a cultivated plot of land between 20-30 acres, ed.) fields, which had been granted to the city by Polish King Kazimierz already in 1356. The land remained long undeveloped either as pasture or for construction. According to Zygmunt Stankiewicz, already in the mid-17th century, “there’s nothing to report about the local thickets, bogs, or hills, and only wild animals and evil people seek refuge in these isolated stretches, and the locals avoid the place”, (Stankiewicz, 1928, p67).In the 19th century this dismal situation took a turn for the better. Following the political reforms of the late-1860s, the local city administration and the liberal Lviv establishment tried in every way possible to underscore the particular status of the city as the capital of the autonomous Kingdom of Galicia. It is in this context that the idea of the creation of an expansive park zone in Lviv with a new, great park on this isolated southern outlying region suddenly seemed such a brilliant idea. Work on the park began in 1879 led by the Lviv City Council advisor Stanisław Niemczynowski, (Miasto Lwów, 1896, pp179, 349).

Arnold Röhring, Lviv’s “park inspector” at the time, drew up the plans for Stryiskyi Park, the largest and most impressive of his city landscaping designs. His plans called for 40,000 trees to be planted on the territory. “It was in 1887 that the park which is now the pride and glory of our town came about, with its refined ecology and extraordinarily thoughtful seedling plantings, and its aesthetically arranged paths, routes, lanes, and flowerbeds”, (Stankiewicz, 1928, p67).

But the story of Stryiskyi Park’s development does not end in 1887. Within a year the city had acquired an adjacent parcel of around 30 morgs (approximately 18 hectares, ed.) on the park’s northeast side at a cost of 5,000 zloty (Miasto Lwów, 1896, p227). By the late-1880s – early 1890s, the park’s upper terrace had been laid in, complete with central lane and fountains.

In 1894, the upper terrace hosted the grandiose – especially by Galician standards – regional Expo which was attended by more than 1, 150, 000 visitors. The project was dedicated to the theme of “progress” and to presenting the social, agricultural, and cultural successes of the autonomous Kingdom of Galicia in the best possible light. More than 100 pavilions in varying historical styles were erected on the park territory, including small open air museums, fabriques, and other objects. The exhibition’s chief architect, Franciszek Skowron, is credited with the design of the Expo; he was assisted by Julian Oktawian Zachariewicz, Juliusz Hochberger, Zygmunt Gorgolewski, and other celebrated Lviv architects. “The regional exhibition of 1894 created…an authentic village, marvelously constructed”, (Stankiewicz, 1928, p68). Only a few solitary buildings from this complex have managed to survive until the early 21st century. And thus, this Stryiskyi Park Expo achieved a certain symbiosis with the great European and American Expos of the latter half of the 19th century on which it was modeled.

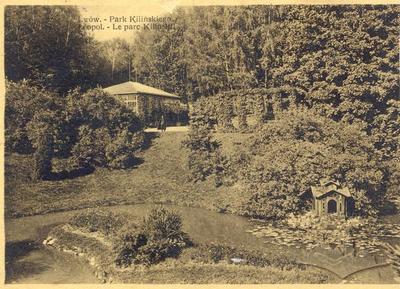

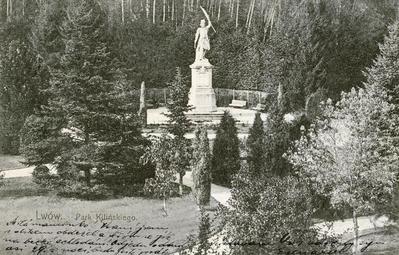

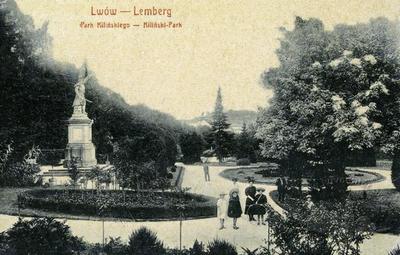

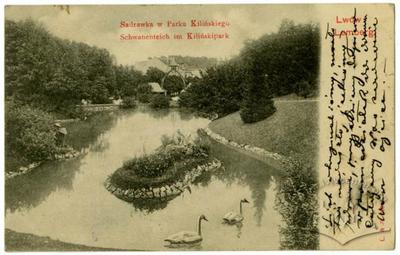

And as the Expo was dedicated to the centennial of the insurrection led by Tadeusz Kościuszko, the exhibition included a pavilion housing a monumental panorama painting of the Battle of Racławice created by Jan Styka, Wojciech Kossak, and several more artists. A memorial statue to Jan Kiliński by Julian Markowski was erected in the park’s lower terrace. Unveiled in 1895, the statue left Stryiskyi Park with yet another name –Kiliński Park. A plant conservatory was also built nearby during that period.

A number of other significant events took place in Stryiskyi Park following the initial 1894 extravaganza, a few of which are listed here: from 1922, the “Eastern Auction” fairs were held here; in the early 20th century, in the park environs football stadiums were built here for the Polish clubs “Blacks”, “Pogon”, “Active Pastime Society”, as well as the Ukrainian “Sokil-Batko” Club (Orłowicz, 1925, p10).

In the 1950s, architect Heirich Schvetsko-Vinetskyi designed an entrance architrave for the Parkova Street approach to the park. The former ‘palace of artists’ and the Racławice Panorama rotunda were converted into sports facilities and the park was enlarged by annexing a portion of the former “Eastern Auctions” section. At this time a so-called “children’s park” was added with a narrow-gauge railway, built at the site of the old Sokil-Batko FC stadium, (Architecture of Lviv, 2008, p603).

Architecture

Stryiskyi Park is located north of the city center. At the close of the 19th century it was bordered on the south by the outlying areas of Kulparkiv and Persenkivka, on the north by the territory of the historic Stryi Cemetery (closed already in the previous century). It was touched on the east by the Hanlivska (Sofiivka) Road and on the west by Stryi Road (later, Stryiska Street). The park territory occupied the heart of Lviv’s former first administrative district, the old Galician suburb. The territory of the future park remained an inaccessible, swampy waste and overgrown gulch until the end of the 1870s.On modern maps of Lviv, the Stryiskyi Park district is shaped like a wedge between the start of Stryiskyi Street, Samchuka Street, and the terminus of Franka and Kozelnytska Streets. On its north and west are Bohdan Khmelnytskyi Park and the Infantry Academy, on its east – the villas of the Sofiivka neighborhood. Parkova Street leads to the main entrance of the park on the lower terrace side and its architectural ensemble from the late-1890s.

In the late 19th century the establishment of a public park on the city’s southern outskirts was guided by the logic of the direction of Lviv’s municipal territorial development. At that time the city’s ‘green zone’ enclosed its historic center bi-directionally: on the east and on the west. Along its eastern edge Lviv had the established park zone that included Vysoky Zamok, Lonszanivka, Lychakova, Pohulianka, and Sofiivka parks. On its west side it had the dynamic growth of fashionable estates and gardens of Lviv’s “West End” which bordered on the Jesuit Gardens. The establishment of a large, new park on the city’s south side would join the urban parklands in a single system, a unified ring of green (similar to the park systems of the cities of Manchester and Liverpool).

Stryiskyi Park is laid on hills which are part of the Lviv Heights. Its structural axis runs along valley formed by Soroka Creek, which was a tributary of the Poltva River. It is here that the park’s central lane has been placed with curving paths leading from it up the slopes to the upper park terrace. “Kiliński (Stryiskyi) Park is on the south side of the city…it was created in 1879 on a lovely parcel of land where a clean breeze blows. As the city’s largest and least complicated park, it quickly became a favorite place for walkers”, (Miasto Lwów, 1896, p320).

The park’s layout serves as testimony to the professionalism of its designer, Lviv parks inspector Arnold Röhring, and his particular genius with landscaping. His ideas for Stryiskyi Park were taken from the landscaped pleasure garden approach already successfully employed in Lviv by Karl Bauer.

This project traces its genesis to the “English” park, and yet, as in most Lviv parks, it evidenced a departure from the sentimental symbols and tendencies so common to the era of romanticism. Lviv’s Stryiskyi Park is a typical city park built during the era of positivism and ‘scientific’ historicism. Indeed, in a further departure from the English park style of the 18th century, Stryiskyi has a clearly defined outer boundary. Its territory is crisply delineated by the surrounding blocks and thoroughfares.

The paths and lanes of Stryiskyi Park (excepting the upper terrace) have an informal structure in the manner of the English park. A pond with swans is also an important compositional element. Yet it is important to note the lanes’ informal arrangement and the uneven contours of the pond are the result of thoughtful design. In a departure from the half-tone, classic English park, the territory of Stryiskyi Park evidences fluid contrast and rich palette: “the lovely carpet of flowers that surround the swan lake during the growing season lend to its attractiveness and splendor…”, (Miasto Lwów, 1896, p320). Stryiskyi Park unites the features of the pleasure garden with those of the woodland park.

Lawns and picturesque walks run throughout the park; they possess a more formal, “French” structure in those areas of the park where there are/were structures (the 1894 Expo pavilions). The upper terrace is modeled on the baroque-classical park. With terraced flower beds and circles, fountains and structures sitting near the central lane and reflecting a Beaux-Arts sensibility. (One may recall that the Hetman’s Ramparts post-1888, and the lower part of the Jesuit Gardens adjacent to the Galician Council house also reflect this academic movement in architecture).

The character of Stryiskyi Park thus evolved as a stylistically eclectic park dating from the era of historicism, yet one that deliberately and fluidly combines various aspects of a historical garden-park aesthetic. The park is comprised of three parts, each with distinctive landscaping and layouts: the lower park, the upper park terrace, and the later-constructed children’s park.

According to Michał Kowalczuk, in the park of the mid-1890s grew “red and sycamore maples, chestnut, alder, birch, weeping beech, oak, sycamore, acacia, linden, and different kinds of pine, fir, juniper, yew, larch, American pine, and a large variety of shrubbery” (Miasto Lwów, 1896, p320, and repeated in Krypiakevych, 1991, p.113).

Here we are again obliged to point out a difference with the 18th century English park: Stryiskyi Park reflects a naturalistic ecology and configuration though, indeed, one which combines botanical variety in a way never encountered in nature. Its botanical arrangement includes a section of imported flora and - what were in that period - exotic plants. For instance, the park has a Gingko tree, a species now seen only in botanical gardens.

According to the reports of Olena Stepaniv, “the park soil is clay, with a sandy mix in places, loam here and there, largely dry, though suitable for a park” (Stepaniv, 1992, 44).

In the 1890s the total area of the park stood at 47.61 hectares (Miasto Lwów, 1896, p320), a number which has grown over time, and the park now covers 52 hectares.

Related buildings and spaces

People

Karl Bauer– landscape architect, park designerJuliusz Hochberger – architect

Zygmunt Gorgolewski – architect

Julian Oktawian Zachariewicz – architect

Kazimierz III – King of Poland

Jan Kiliński – Polish insurgent

Michał Kowalczuk – architect, architectural critic, guidebook author

Wojciech Kossak – artist

Tadeusz Kościuszko – leader of the Polish insurgency

Julian Markowski – sculptor

Stanisław Niemczynowski – civic activist, city counselor

Franciszek Skowron – architect

Zygmunt Stankiewicz – engineer, ethnographer

Olena Stepaniv – historian, geographer, civic activist

Jan Styka – artist

Arnold Röhring – landscape architect, park designer

Heinrich Schvetsko-Vinetskyi – architect

Sources

- Architecture of Lviv: Times and Styles, 13th-21st centuries. Biriulyov, Yuryi, ed. Lviv: Center of Europe Publishing, 2008.

- Barański, F. Przewodnik po Lwowie: Z planem i widokami Lwowa. Lwów: 1902.

- Krypyakevych, Ivan. Historical Walks Around Lviv. Lviv: Kamenyar, 1991.

- Miasto Lwów w okresie samorządu 1870-1895. Lwów: 1896.

- Orłowicz, M. Ilustrowany przewodnik po Lwowie: Ze 102 ilustracjami i planem miasta. Wydanie drugie rozszerzone. Lwów – Warszawa: Książnica-Atlas, 1925.

- Posatskyi, B. “The Architecture of Totalitarianism (1940-1956) ”, Architecture of Lviv: Times and Styles, 13th-21st centuries. Biriulyov, Yuryi, ed. Lviv: Center of Europe Publishing, 2008. pp. 578-605.

- Stankiewicz, Z. „Ogrody i plantacje miejskie”. Lwów dawny i dzisiejszy: Praca zbiorowa pod redakcja B. Janusza.Lwów: 1928, p. 62–71.

- Stepaniv, Olena. Contemporary Lviv: A Guidebook. Lviv: Phoenix, 1992.

Citation

Ihor Zhuk. "Stryiskyi Park". Lviv Interactive (Center for Urban History, 2012). URL: https://lia.lvivcenter.org/en/objects/park-stryiskyi/Urban Media Archive Materials