Vul. Sianska, 16 – former Great Suburban Synagogue ID: 432

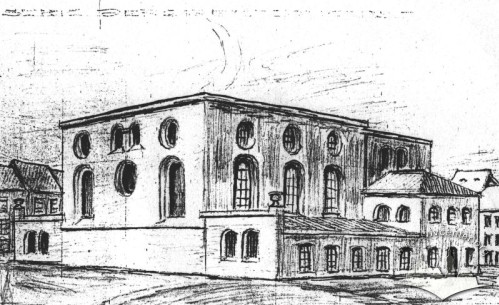

The suburban synagogue in the former Krakivske suburb was a defensive structure. During all its existence, its appearance changed several times. In autumn of 1941 the synagogue was blown up by the Nazis, and its ruins were dismantled in the late 1940s.

Story

10 July 1624 — king Zygmunt III (Sigismund III) granted permission for the construction of a synagogue in the Krakivske suburb.1632 — the synagogue's basic block with the men's prayer hall was constructed.

1635 — south women's galleries, or ezrat nashim, were added by permission of king Władysław IV.

Late 17th–early 18th c. — a women's gallery over the pulish (vestibule) was built

Mid-18th c. — the synagogue was covered with a high Baroque-style mansard roof.

1864-1865 — the entrance and small windows to the prayer hall from the south women's gallery were bricked up (architect Józef Engel).

1871 — the synagogue was reconstructed under a project designed by architect Michael Gerl: a tier with round windows was added and a low roof was arranged.

1912 — the wooden ceilings in the west women's galleries were replaced with concrete ones.

1914 — the vestibules in the side galleries were reconstructed (architects Włodzimierz Podhorodecki and Henryk Salver), beams were restored, electric lighting was installed in the women's part (engineer O. Piotrowski), sixteen windows were installed, etc.

1919 — the façades were repaired; the authentic vault of the ground floor women's galleries was replaced without permission; painting works were carried out by the "Bracia Fleck" company.

1920 — the works, managed by Leopold Reiss, were finished: the wooden ceiling of the pulish was replaced with a reinforced concrete one. Under his project, the main entrance in the main façade was arranged. The synagogue's walls were covered with paintings designed by brothers Fleck.

Autumn of 1941 — the synagogue was blown up by the Nazis.

Late 1940s — the ruins of the synagogue were dismantled.

Ancient synagogues of the Krakivske suburb were wooden. Because of frequent fires their age was short-lived. They were located very close to the city walls, near the Krakivska gate, in the midst of the Jewish district's rather dense housing. One of these wooden synagogues was depicted by Martin Gruneweg, a traveler and chronicler, who attached the drawing to his description of Lviv. Gruneweg, who lived in Lviv from 1582 to 1601, in his late 16th century diary observed: "In my days, a new synagogue was built on the site of the old one. While building it, the roof was made too high... because of it, they had to pay a fine and to lower the roof by half, so now it seems broken" (Gruneweg, 1980).

This synagogue can be seen in the oldest drawing of Lviv, made by Aurelio Passaroti in 1607-1608, and in an engraving by Frans Hogenberg, based on the drawing of Passaroti and published in 1618 (Kostyuk, 1989).

In front of the synagogue, there was an area with Jewish kiosks where trade was carried on. In 1619 the Jesuit school students devastated the Jewish district, destroying the synagogue almost completely. It was rebuilt, but already in 1623 it was burned down in a great fire, along with the rest of the Krakivske suburb's buildings. After the fire the Magistrate prohibited erecting any buildings at a distance shorter than 400 cubits from the city walls. A contract, granted by king Zygmunt III on 10 July 1624, provided for a number of permissions for the suburban Jews: they were allowed to build up a new street (i.e. a district) stretching from the Poltva river eastward to the Benedictine nuns' convent; to build a synagogue in another place: in the lowland of the so-called Poznański yard, which stretched from the old synagogue northward up to the square of St. Theodore; to buy plots for the construction of their own homes at the city wall. From 1462 the yard was owned by a Jewish family; in particular, in the early 17th century it belonged to Abraham Moszkowycz, a landowner and a possessor (Bałaban, 1990, 21; Bałaban, 1906, 214).

For the construction of a new synagogue permission was needed from the Catholic authorities. Granting it, the then Archbishop of Lviv Andrzej Pruchnicki warned: "... the infidel Jews should not build a magnificent and costly synagogue, but just a large and average one". In particular, it was noted in the resolution that "...the dome should be modest, lowered by three parts, in the Italian way" (Bałaban, 1990, 21; Bałaban, 1924).

The stone synagogue was constructed in 1632. Originally it consisted only of a large square prayer hall (20.10 x 19.28 x 11 m), indicating a numerous community. In 1635 king Władysław IV gave his consent to the construction of a women's prayer room (ezrat nashim) (Kapral, 2001).

After the completion of the latter, the synagogue size was approximately 24 x 35 m. It looked like a large cubic structure, dominating in the middle of the densely built-up Jewish district, and had a high pyramidal mansard roof. The women's galleries were covered with a folded-plate roof. Lest the synagogue should rise above residential buildings, as was required by the contemporary law or devotional duties, the high prayer hall was recessed by nine steps. According to the then requirements, in case of an attack the synagogue should serve as a defensive structure. Although it is not recorded in the documents, but we know that the Great Suburban Synagogue withstood more than one siege, especially in the second half of the 17th century. Since to successfully stand a siege it was necessary to be able to shot from the top, initially the synagogue walls must have had a loopholed defensive attic hidding a folded-plate roof, typical of ancient stone synagogues. In Lviv of that time, Renaissance-style attics decorated patrician townhouses in the Rynok (Market) square and the town hall, as well as some sacred buildings, including the tower of the Benedictine monastery (1627) and the Nachmanowicz synagogue (1582). The synagogue's Renaissance-style attic was probably destroyed during the pogroms of the Jewish district. Around the mid-18th century the synagogue was covered with a high fractured Baroque-style roof, as seen in a 1772 engraving by Perner.

Unfortunately, the name of the author of the Great Suburban Synagogue has not been discovered. According to Sergey Kravtsov's hypothesis, it could be a guild master Jakub Medlana (Giacomo Madlena) who came from the Swiss canton of Graubünden. However, he could not complete the synagogue as he died in 1630, while the building was finished only in 1632. Ambroży Przychylny, the chief assistant of Paweł Szczęśliwy during the construction of the "Golden Rose" synagogue, and his constant partner Adam Pokora (de Larto) were probably involved in its construction. Przychylny and Pokora established good relations with Lviv Jews; in particular, they built a townhouse for Solomon Friedmann, a wealthy citizen, on what is now Staroyevreiska street 34. Ambroży Przychylny (d. 1641) arrived in Lviv in the late 16th century from the town of Engadin in the canton of Graubünden, Switzerland, and in 1591 was accepted as a master to the Lviv guild of stonemasons; he was several times elected the junior guild master, and in 1613 and 1630 he was elected the senior guild master. After the death of Paolo Romano, a famous Lviv builder, Przychylny married his widow, a daughter of Wojciech Kapinos, who accompanied him in completing the Assumption Church.

It was due to the Great Suburban Synagogue huge size that a new constructive solution was invented: four columns carried a system of ceilings consisting of nine equal vaults. An important factor was also new canons established by Mosche Isserles, a Krakow rabbi (1530-1572); according to them, the Bimah should be located in the middle of the prayer hall. The Lviv Great Suburban Synagogue became the prototype of many Jewish shrines built according to a nine-field planning and spatial pattern. European scientists, including Georges Lukomsky, called the nine-field synagogue "the Lviv type". The fact of its appearance in Lviv was obviously influenced by the then local sacral architecture, whose most famous examples included cross-in-square churches of the Byzantine type: the old church of St. George (1363) and the Armenian Church (1363), erected by builder Dork, as well as the Ruthenian (Assumption) church (1629), which was built by Paolo Romano and Ambroży Przychylny.

The gloomy appearance of the Great Suburban Synagogue plain façade was similar to the Lviv churches of that time, including the church of St. Lazarus, built by Przychylny, or the architectural complex of the Benedictine nuns' convent. The attic over the profiled stringcourse could be similar to the attics of Lviv patrician townhouses (e.g. the Lorentsovychivska-Anchevska townhouse), the town hall or the castle in the village of Stare Selo, built under the management of Przychylny.

In old times in the Great Suburban Synagogue vestibule the pillar of shame was established, and those condemned by the court of the community were tied to it.

The names of some prominent figures of Jewish culture are connected with the synagogue located in Lviv's Krakivske suburb. In particular, in 1652-1667 years its Rabbi was Dawid Ha-Lewi Segal, one of the most famous commentators of the ritual code of Yozef Caro, the author of a well-known work entitled "Ture Zahav".

Even in the mid-19th century the Great Suburban Synagogue looked like a Renaissance building covered with a Baroque-style roof. From archival materials the synagogue's later construction history is known. Throughout its existence, it was expanded and various extentions were added spoiling its appearance and causing destruction. In particular, a second tier added to the south women's gallery, whose wall was laid directly on a vault, caused cracks in the latter. In 1864-1865 at the suggestion of architect Józef Engel, the entrance and a small window to the prayer room were bricked up (ДАЛО 2/1/731: 4-5, 39).

The general condition and appearance of the synagogue required a renovation. In 1870 the community leaders Chaim Birnbaum and Schmelke Sokal commissioned architect Michael Gerl to design a project for its reconstruction. After the reconstruction under this project in 1871 the synagogue became a Neoclassicist-style building. To the Great Suburban Synagogue, small sanctuaries were attached in the mode of separate chapels, including those belonging to the guilds of tailors and butchers, prayer rooms of brotherhoods, Talmudic schools and others.

In 1926, it housed small synagogues of different societies — "Hayutim Gedolim", "Menakrem", "Melamdim". "Nosey Katov", "Sovhe Tzedek". All seats in the synagogue were secured for their owners, they were sold or inherited, the situation evidenced by a lawsuit for a place.

Even before the First World War, in 1912, a reconstruction of the Great Suburban Synagogue started under projects designed by two architects, Włodzimierz Podhorodecki and Henryk Salver. Under the project of Podhorodecki, the replacement of wooden ceilings with concrete ones was started in the west women's galleries. However, the work was more than once interrupted because of warfare. In 1914 the side galleries' vestibules, damaged during the war, were reconstructed. The beams were restored and electric light was installed in the women's part (engineer Oskar Piotrowski), sixteen windows were arranged, etc. During the war rafters over the exterior galleries were partially burned down (ДАЛО 2/1/731: 12; ЦДІАЛ 701/3/217).

The synagogue suffered damage in the time of the November 1918 pogrom, committed by Polish lumpenproles. The interior was partially damaged at that time. In memory of these events, a plaque reading "In memory of the fire, which occurred in the days of the pogrom on 19 Kislev 5579" was installed over a column capital, intentionally left unrestored.

The postwar reconstruction works were carried out under a project designed by Leopold Reiss and approved by the Grono konserwatorskie. In 1919 the plastering of the façade, begun in 1914, was finally finished. The distinctive vaults in the ground floor women's galleries were replaced without permission. The painting works were done by the "Bracia Fleck" company. In 1920, under the management of Reiss, the wooden ceiling in the pulish was completely replaced with a reinforced concrete one and the floors were relaid. It was under the same architect's project that the main entrance was arranged in the main façade. Under a project designed by Gerl, the west façade had entrances on the extreme axes of its seven-axis main part. Reiss suggested that a central entrance with three doors should be arranged. On the inside, this entrance looked quite presentable, with stairs leading to the recessed pulish. Between the doors, there were two aspersoria on pedestals. The Grono konserwatorskie had several comments on the project designed by Reiss: the modest rails should be installed at the wall and not separately on balusters; the place at the aspersorium should be paved with stone plates and not with chamotte ones; given the fact that this is a monument, any changes must be coordinated with the Magistrate, and especially the reconstruction of the two side vestibules for women; the ancient art baldachino should be fixed and cleaned. All steps must be made of Ternopil or Terebovlia stone. The works were carried out by Andrzey Jaworski, a stonemason who was commissioned by Reiss to make the stairs; L. E. Schrage who was responsible for woodwork; N. Belicki and Bautmusereich who were responsible for metalwork and metal products. In 1919-1926 the Great Suburban Synagogue's community leaders were Chaim Wolf Taube, Dawid Reicher, Hersch Karl, Eizig Rappaport, Mojszesz Horowitz, Mojszesz Zic, Chaim Israel Friedmann (ДАЛО 2/1/731: 2-3, 33, 35-38; ЦДІАЛ 701/3/553).

The synagogue's walls were covered with paintings under a project designed in 1918 by brothers Eryk and Maurycy Fleck. The Suburban Synagogue was a rich shrine, as evidenced by its inventory, compiled in 1920. Among the synagogue items the following ones were notable: a very large silver and gilded crown of the Torah, one large and two small crowns, a lot of silver utensils like trays, boxes, cups (one dating back to 1662), six chandeliers, lanterns, twelve kaporets, thirty-seven Torahs, of which twenty-one not used, one horn shofar, two Megillah scrolls, candlesticks (ЦДІАЛ 701/3/1101 б).

The Great Suburban Synagogue was blown up by the Nazis in autumn of 1941; its ruins were dismantled during the Soviet occupation of Lviv in the late 1940s. Today there are kiosks of the Dobrobut market in its place. The remains of the synagogue are covered with a layer of soil, raised above the day surface. It is probable that in the course of archaeological excavations it would be possible to discover the foundations and fragments of buildings.

Architecture

Originally, the Great Suburban Synagogue of Lviv was a typical defensive structure, which looked like a cubic block covered with a folded-plate roof and topped with an attic. In the 18th century it had a high Baroque-style mansard roof, which was replaced with a low one in 1871, with the raising of walls having round windows which illuminated the attic. The east wall was accentuated by two paired windows resembling the tablets of the covenant. The block of the main prayer hall was on three sides (south, north, and west) encircled by lower synagogue extentions. The cubic main prayer hall was lighted through elongated semicircular windows, three in each of the north and south walls; in the east wall, two arched windows with a round window between them were arranged. The west façade could be arranged along the same compositional pattern. The pattern with a round window on the axis of the east and west façades was used in the ancient synagogues of Sataniv (1630), Husiatyn (17th century), Medzhybizh and other towns. Later, when a women's gallery was built over the Suburban Synagogue's pulish, three large three-centered openings were arranged in the west wall of the prayer hall to connect it with the matroneum; after the second tier of the women's galleries was constructed, the elongated windows on the axes were replaced with round ones. The main block's north and south façades were adjoined by the ground floor women's galleries, covered with cross vaults and connected with the prayer hall by distinctive small window openings, six in each of the north and south walls.A spacious prayer hall, whose area was almost 400 square meters, was covered with a system of cross vaults supported by four octagonal columns (1.23 m thick) with Corinthian capitals. Thus the planning structure of the men's prayer hall became a three-nave and hall-type one. Columns and arch walls divided the prayer hall ceiling into nine almost equal fields (the central one was the smallest). The position of columns, distanced from the Bimah, made it possible to avoid a shortcoming, characteristic of those synagogues, where the Bimah in the form of four pillars was, due to its massiveness, too isolated from the community. A new monumental design significantly increased the interior space, drawing attention to the Bimah.

The centricity of the men's prayer hall in "Lviv-type" synagogues was emphasized by the identical layout of the walls. The peculiarity of the vault in nine-field synagogues led to their three-part structure. Each wall was divided by a rhythm of pilasters into three parts with a window in each. The east wall was somewhat different as the Aron Hakodesh was placed on its axis. The light fell into the room from three sides through large window openings. Apart from a vertical division by pilasters, the prayer hall walls were divided horizontally. A decorative belt with a motif of the blind arcade in the form of triforia ran below the windows. In the blind arcade fields, the signs of the zodiac were located: a decorative motif associated with the twelve tribes of Israel. The magnificently decorated Torah niche had an original marble framing with a perfect combination of arabesques and letters, with the words "God helped on that day" entwined with them. On the east wall, on both sides of the Aron Hakodesh, there were oil paintings with verses from the Psalms and the Pentateuch. In other oil paintings, the landscapes of the Mount of Olives, Jerusalem, Bethlehem, the Temple Mount and some others were depicted. At the altar, a brass Menorah was located, cast by K. Frank, a foundryman from Wroclaw, in 1775.

The Great Suburban Synagogue's peculiar feature was a gallery for students (3.38 x 0.79 m), arranged at the prayer hall west wall at a height of 4.15 meters, which could be accessed via fifteen steps with a forged metal handrail. This gallery was unique, as no other synagogue had anything like that in Poland of that time. In the southwest corner of the main prayer hall, at the door, an oil lamp with eternal flame (Ner Tamid) was arranged.

In 1918 the synagogue walls were covered with unique paintings designed by brothers Eryk and Maurycy Fleck. On a piece of cardboard, which has been preserved, some fragments of these murals are shown in saturated colors. Traditional symbolic images were depicted in the midst of magnificent plant decoration. In particular, the Torah was depicted to the left of the window with the shield of David, the Menorah with the Star of David – to the right of that window. In a belt under the blind arcade, filled with inscriptions, two framed paintings from the Promised Land were placed: the Wailing Wall and Rachel's Tomb. In the corners of the sailing vault, four symbolic animals were depicted: a lion, an eagle, a deer and a bull.

People

Bautmusereich — a carpenterBelicki N. — a carpenter

Chaym Birnbaum — a head of the Jewish community

Yozef Caro — author of the famous "Ture Zahav" work

Józef Engel — architect

Eryk Fleck — artist and decorator

Maurycy Fleck — artist and decorator

K. Frank — foundryman from Wroclaw

Solomon Fridmann — wealthy Jewish Lviv citizen

Chaim Israel Fridmann — one of the heads of the Great Suburban Synagogue's community in 1919–1926

Michael Gerl — constructor

Martіn Gruneweg — traveller and chronicler

Dork — architect of old (14th c.) churches in Lviv, St. George and Armenian church among them

Frans Hogenberg — engraver

Moises Horowic — one of the heads of the Great Suburban Synagogue's community in 1919–1926

Mosche Isserles — a rabbi from Krakow

Andrzey Jaworski — a stonemason

Wojcech Kapinos — a guild constructor from Lviv

Hersch Karl — one of the heads of the Great Suburban Synagogue's community in 1919–1926

Sergey Kravtsov — architect, born in Lviv, professor at Jerusalem University

Georgiy Lukomski — Russian scholar

Jakub Medlana — Lviv guild constructor, who came from the Swiss canton of Graubünden

Abraham Moszkowycz — a landowner and a possessor who owned the Poznański court in early 17th c.

Aurelio Passaroti — fortification engineer

Oskar Piotrowski — engineed

WłodzimierzPоdhorodecki — architect

Adam Pokora / deLarto — Lviv guild constructor

Andrzej Pruchnicki — Lviv archbishop

Ambrozy Prykhylnyi — Lviv guild constructor

Eizig Rappaport — one of the heads of the Great Suburban Synagogue's community in 1919–1926

Dawid Reicher — one of the heads of the Great Suburban Synagogue's community in 1919–1926

Leopold Reiss — architect

Paolo Romano (Paweł Rzymianin) — Lviv guild constructor

Henryk Salver — architect

L. E. Schrage — a carpenter

David Ha-Levi Segal — synagogue's rabbi, one of the most famous commentators of the ritual code of Yozef Caro

Schmelke Sokal — Lviv guild constructor Lviv guild constructor

Paweł Szczęśliwy — Lviv guild constructor

Chaim Wolf Taube — one of the heads of the Great Suburban Synagogue's community in 1919–1926

Moises Zic — one of the heads of the Great Suburban Synagogue's community in 1919–1926

Zygmunt III (Sigismund III) — Polish king

Sources

- Державний архів Львівської області (ДАЛО), 2/1/731.

- Центральний державний історичний архів України у Львові (ЦДІАЛ), 3/217/277.

- ЦДІАЛ, 3/217/333.

- ЦДІАЛ, 3/217/553.

- ЦДІАЛ, 3/217/683.

- ЦДІАЛ, 3/217/1101.

- Бойко О., "Будівництво синагог в Україні", Вісник інституту "Укрзахідпроектреставрація", (Львів, 1998, ч. 9).

- Бойко О., "Оборонні синагоги Західної України", Народознавчі зошити, (Львів, 2000, ч. 2).

- Вуйцик В. "До питання про об’ємно-планову композицію старої катедри Св. Юра", Вісник інституту "Укрзахідпроектреставрація", (Львів, 2004, ч. 4).

- Геврик Т., "Муровані синагоги в Україні і дослідження їх", Пам’ятки України, 1996.

- Груневег М., "Найдавніший історичний опис Львова", Жовтень, 1980, № 10.

- Зіморович Б., Потрійний Львів (Львів, 2002).

- Зубрицький Д., Хроніка міста Львова (Львів, 2006).

- Історія Львова в документах і матеріалах (Київ, 1986).

- Історія Львова (Львів, 2006, Т. 2)

- Капраль М., Національні громади Львова XVI–XVIII ст. (соціально-правові взаємини), (Львів, 2003).

- "Каталог синагог", Вісник інституту "Укрзахідпроектреставрація", (Львів, 1998, ч. 9).

- Костюк С., Каталог гравюр XVII–XX ст. з фондів Львівської наукової бібліотеки ім. В. Стефаника АН УРСР (Київ, 1989).

- Кравцов С., "О происхождении девятипольних каменних синагог", Еврейское искусство в европейском контексте, (Иерусалим-Москва, 2002).

- Кравцов С., "Синагоги Західної України: стан і проблеми вивчення", Вісник інституту "Укрзахідпроектреставрація", (Львів, 1994).

- Меламед В., Евреи во Львове (XIII – первая половина XX века), (Львов, 1994).

- Наконечний Є., "Шоа" у Львові (Львів, 2004).

- Bałaban M., "Bożnice obronne na wschodnich kresach Rzeczypospolitej", Nowe życie, (Warszawa, 1924, 199).

- Bałaban M., Dzielnica żydowska: jej dzieje i zabytki, Biblioteka Lwowska. (Warszawa, 1990, т. III).

- Bałaban M., Żydzi lwowscy na przełomie XVI i XVII wieku (Lwów, 1906).

- Czerner O., Lwów na dawnej rycinie i planie (Wrocław, 1997).

- Grotte A., Deutsche, böhmische und polnische Synagogentypen vom XI bis Anfang des XIX Jahrhunderts (Berlin, 1915).

- Kapral M., Przywileje królewskie dla lwowskich żydów w XIV–XVIII wieku (Studia Judaica, 2001, № 1–2).

- Kowalczuk M., Cech budowniczy we Lwowie za czasów polskich (do roku 1772), (Lwów, 1927).

- Kravtsov S., "Gothic Survival in Synagogue Architekture of Ruthenia, Podolia and Volhynia in the 17th–18th Centuries", Architectura (Műnchen-Berlin, 2005, № 35).

- Kravtsov S., Juan Bautista Villalpando and Sacred Architecture in the Seventeenth Century (Jsan. – 64:3, September, 2005).

- Schall J., Historia Żydów lwowskich (Lwów, 1936).

- Schall J., Przewodnik po zabytkach żydowskich Lwowa (Lwów, 1935).

- Zajczyk Sz., "Architektura barokowych bożnic murowanych w Polsce", Biuletyn naukowy Politechniki Warszawskiej (Warszawa, 1933).