Vul. Ivana Fedorovycha, 27 – former Golden Rose Synagogue (Taz, Turey Zahav) ID: 274

The synagogue was constructed in Renaissance style in 1582-1595 from brick and stone by architect Paweł Szczęśliwy (Pavlo Shchaslyvyi) and funded by the wealthy Nachmanowicz family. The synagogue would have been one of the oldest within the current borders of Ukraine. Yet in August 1941, all its religious objects were plundered and in 1943 it was demolished by explosives by the Nazis. The ruins that remain today, long neglected but undergoing some preservation efforts recently, are a symbol of the tragedy of Lviv’s Jews.

Story

1582 – Synagogue’s main section, with men’s prayer-hall was constructed.1595 – prayer hall extended by adding a porch. Three arched apertures hewn through the prayer-hall’s western wall, divided by two strong angular columns. Galleries added above the new western part of the synagogue joined with the prayer hall by means of three hewn-through windows. Floor of the prayer-hall laid with stone. Walls covered with wall-paintings.

1601 – southern galleries added

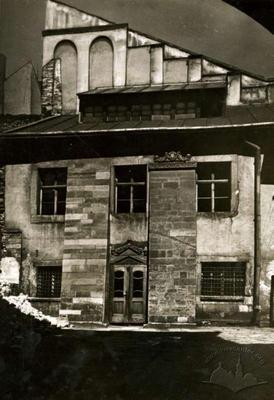

Late 18th century – small porch added to synagogue from the side of the courtyard with a Hebrew inscription above the entrance: “Our teacher and Rabbi David Ha-Levi prayed here”.

1603 – Kahal moves its insignia and the courhouse to the synagogue. The Nachmanowicz synagogue becomes “Great City Synagogue”.

1606 – after extensive court proceedings the synagogue was transferred to the Jesuits, while the community moved to their old synagogue.

1664 рік – many valuable reliquaries stolen from the synagogue.

Eighteenth century – attic dismounted

1801 – the synagogue diminishes in significance.

By 1863 – the synagogue’s condition unsatisfactory

1914 – stairs, threatening to collapse, taken apart. The original arch-roof over the porch, dating from 1595, as well as the arch-roofs of the side galleries, were removed. New arch-roofs constructed, not appropriate for the building.

1915 – reconstruction of two stone columns and heads, clearing of arcades and stone columns above the capitols of first-floor pillars by mason Wojciech Jabłoński; photofixation by Wlodzimierz Podhorodecki (Volodymyr Pidhorodetsky).

1917 – reconstruction of two columns (foundation widened and crumbled stones replaced under one) by master mason (carver) Aloiz Traversa.

1918 – the Conservation Society joins the renovation effort, proposing to restore the synagogue in its original appearance.

1921 – the once-dismounted vaults reconstructed and walls repaired; the strengthening of columns concluded in changing their hexagonal section to a rectangular one with concrete bases. Renovation work proceded according to a project by Reis. All of the wall-paintings were plastered over, the whitestone borders of the windows were destroyed, etc.

1934 (June 26) – synagogue proclaimed a national monument of architecture.

1941 – the synagogue is robbed of all its reliquaries.

1943 – the synagogue is demolished by the Nazis. Janusz Witwicki takes measurements of the remaining ruins and performs reconstruction project.

2007 – archaeological excavations held on the site of the Golden Rose.

The “Golden Rose” synagogue was one of the most spectacular late-sixteenth-century Renaissance architectural landmarks of the city. Constructed in 1582 (as evidenced by a Hebrew inscription on the keystone in the center of the ceiling, bearing the date כשם ויקדא, or the year 5342). Initially, it was constructed as a private synagogue for Yitzhak ben Nachman (Nachmanowicz), a senior of the Jewish Assembly in Lviv, President of the Lublin Jewish Diet in 1589, a chief financier of the Polish King Stefan Batory, and one of the richest city residents. In 1580, Nachmanowicz acquired a parcel of land from the city authorities, known as the Olesko Lot. It owed its name to Jan z Sienna, a Polish landowner of Olesko town, who had received this parcel of land as a gift from the Polish king in the middle of the fifteenth century. The Olesko parcel stretcged from former Żydowska Street (also known as Blacharska Street, Fedorova Street) to the city walls, while the so-called Olesko House stood in place of today's building No. 27 on Fedorova Street. The house later deteriorated, and the vacated area was filled with new buildings. A brothel was built in the backyard, while closer to the street, and occupying the breadth of the parcel, a treadmill (kerat) was constructed, leaving only a narrow lane leading to the brothel. In front of the treadmill was an empty space left from a building lost to fire, which was separated from the street by a fence. The brothel stood close to the city walls, on a spot where later the house of the Suskint (Suskintowicz) family was constructed (today Arsenalna Street, Nos. 3 and 5), with its windows facing the square and the treadmill.

In 1571 a devastating fire occurred, destroying the entire southeastern part of the city. All of Ruska Street with the Assumption Church, the entire Jewish district, the city armory and the fortification towers, as well as the treadmill and the brothel went up in flames. It was after the fire that the fire-devastated Olesko Lot was bought by an elder of the city's Jewish community Yitzhak ben Nachman (Nachmanowicz). The building of the synagogue arose in place of the treadmill that had been devoured by flames in 1571. The laws of the day required the Polish king’s permission for construction of the synagogue. Nachmanowicz received the permission on 24 March 24 1581. Wishing to impress the city community, Nachmanowicz invited one of the most renowned city architects, Paweł Szczęśliwy (Pavlo Shchaslyvyi), who came from Northern Italy and designed many representative buildings in the city. Szczęśliwy’s authorship is confirmed by papers, dating from 1604 and 1606 in connection with court proceedings between the Jesuits, who had recently arrived in the city, and the Jewish community, for the synagogue's land, where the Jesuits wanted to build their residence. The testimony from Szczęśliwy, whom the papers mention as a mason, confirms the auhorship of the synagogue: “I was building the new school…”. (Source: Архів інституту «Укрзахідпроектреставрація», спр. Л-37/3 Александрович В. Руїни синагоги «Золота Рожа»; Вуйцик В. Львів – місто европейське // Вісник інституту Укрзахідпроектреставрація. – Львів, 2004. – Ч. 14. – С. 182-184.; Jaworski F. Złota Róża // Tydzień. Dodatek do Kurjera Lwowskiego. – Lwów, 1902. – № 32. – S. 502).

Additionally, Szczęśliwy testified in court to having constructed all the buildings in Oleska Square – a blacksmith’s forge, followed by the house of Mordechay ben Yitzhak (Mark Isakowicz, today Fedorova Street, No. 27), the house of Yitzhak ben Suskint (Isaac Suskintowicz, today on Zaarsenalna Street), and the synagogue. Constructed in 1582, the building was small, and almost a perfect square in plan. It consisted only of a men's prayer hall, with a small adjacent building from the West side, with a porch and a counsel-parlor. This fact is mentioned by Szczęśliwy: “The school was 18 elbows in length, and [had] two additional vaults.” (Source: Архів інституту «Укрзахідпроектреставрація», спр. Л-37/3 Александрович В. Руїни синагоги «Золота Рожа»).

Nachmanowicz started the construction of the synagogue without prior permission from the Roman Catholic clergy, which later caused him problems. As early as in 1583 Archbishop Jan Solikowski complained to Rome about construction of the synagogue, and the subsequent construction was halted for twelve years. Initially the synagogue remained private, as confirmed by papers retrieved from the Lviv City Archive. For example, on February 13, 1587, local honorable Stanisław Scholz Wolfowicz, whom Nachmanowicz owed money, was granted the right of “intromission,” meaning seizure of Nachmanowicz's house and the new building, referred to as the Jewish School. However, the scope of further construction revealed Nachmanowicz's real intentions, to give the community a new, public prayer house.

In 1594, construction resumed again when Nachmanowicz was granted the permission to construct a women's gallery above the western porch. However, Nachmanowicz’s early death put the plans on halt, and subsequent construction was carried out by his sons Mordechay and Nachman ben Yitzhak. (Marko and Nachman Isakowicz). The women's gallery and porch were added in 1595 under supervision of Szczęśliwy with participation from master masons Ambroży Przychylny (real name Ambrosio Nutclauss), Adam Pokora (de Larto) and Zaccary Sprawny (de Lugano). The 1595 reconstruction is mentioned in a document from the above-mentioned court proceedings, where Szczęśliwy testified that “they [sklepy, the two vaults] were later taken down, after which the [new] vaults made the school circa 30 elbows high. Additionally, above where those vaults [which had been taken down] had been, is a vault, on which the Jewish women hold their prayers.” Przychylny’s testimony offers a somewhat more detailed description:

“This new school is larger than the old one, for it used to be 18 elbows long and 16 wide, but later its two vaults, which had been adjacent to it, had been taken down, and [the new ones were] added, wherefore it now has 28.5 or 29 elbows. Because of this, also, above the place where those vaults had been, there is an arch-roof, above which the Jewish women make their prayers. And there are so many Jewish men, children and women there that when the floor was adjusted or laid in the synagogue, it was impossible to remain there because of the vapors from all the breathing, for there are a great many of them there, and everyone has their own place, paid for, where every Jew has their own bench.” (Архів інституту «Укрзахідпроектреставрація», спр. Л-37/3 Александрович В. Руїни синагоги «Золота Рожа»).

In the course of the reconstruction, the prayer hall was widened by cutting three arched openings in the western wall, divided by two strong angular pillars, and adding a porch. The galleries added above the synagogue's new western wing were joined with the [men’s] prayer hall by means of three windows. All of the new apertures had pointed arched endings. The walls of the synagogue were covered with murals, possibly by a certain Isaac, a local Jewish artist, whose name is mentioned in the municipal records from 1597. Finally, the floor was laid and thus the construction finished.In 1601 Mordechai Isakowicz bought the neighboring Sokolowska parcel (to the south from the synagogue), where he built a scholars’ house in the courtyard, and the women’s galleries of the synagogue. At the same time and at his own expense, Nachman Isakowicz built a hospital on another plot of land (to the northeast from the synagogue), which he had bought for this purpose. Until September 25, 1603, the Nachmanowicz synagogue was a family prayer house, though even in their father Isaac's days visitors were welcome at the services, and allowed to remain at the synagogue for half an hour after. On September 25, 1603 the kahal moved its insignia and the courthouse to the synagogue, which was subsequently known as the Great City Synagogue. Initially the porch of the synagogue also served as a court and place of detention (both institutions were later moved to the neighboring house). However, the very same year, the Jesuit Order was granted lands by the city wall (the eastern part of former Żydowska Street) by the Polish king Zygmunt III based on the assumption that the city council had acted illegally in selling these parcels to the Jews. The king's idea was that the Jesuits should build their monastery here. In 1606, after extensive court proceedings the building of the synagogue was transferred to the property of the Jesuits, whereas the Jews were forced to move to the old synagogue. According to Zimorowicz, “[in] 1608. … the Jews [were] shedding golden tears over the fall of their synagogue, and furthermore their expulsion beyond the city walls.” (Зіморович Б. Потрійний Львів. – Львів, 2002. – С. 141).

However, as the synagogue was in private property and its entrance lay through the house of Mordechai ben Yitzhak (Isakowicz), who did not grant the Jesuits the right to pass there, the prolonged litigation with the Jewish kahal left the Jesuits with nothing. There is a legend connected to these events, according to which the synagogue was saved from claims of the Gentiles by Isaac Nachmanowicz's daughter-in-law, Rosa, who sacrificed herself to the Roman Catholic Bishop of the time, Rev. Zamojski, in his residence. This legend was retold by Majer Bałaban:

«This happened in the days of the Polish kings. The old synagogue was destroyed by fire, and donations were being gathered for the construction of the new one, in stone. Gold was flowing in from different countries that Lwów traded with, and the city itself was rich and pious. The roof of the new synagogue was to be beautiful and high – to be seen from all around, proclaiming far beyond the walls the greatness of the King of Israel. And a bride, pious and kind, lived in the capital of the crownland at the time, named Rose – for even as a rose sends out her aroma, she gave alms to the poor, and her home was ever a refuge for the destitute, the unfortunate, the hungry. Even in her father's home she had been called die guldene Rojze, the Golden Rose, for her kindness. This maiden, who saw and felt her people's pain, sacrificed her entire fortune as ransom for the synagogue. However, the [Roman Catholic] Church authorities would not hear of it. – Let her bring the money herself, – was the Bishop's final word. Rose doubted, for she was a maiden of great and enchanting beauty. However she went to the Bishop and remained [at his residence], in return for which he returned the synagogue to her brothers. Great joy came to the community, and light went out from the windows of the synagogue, which was seen all the way to the Bishop's residence. Rose saw it as well. Having fulfilled her mission, she committed suicide. The Jewish bride is mourned to this day.” (Bałaban M. Dzielnica żydowska: jej dzieje i zabytki // Biblioteka Lwowska. – Warszawa, 1990. – T. III).

The Jesuits harrassed the Jewish quarter many more times, robbing the synagogue. Many reliquaries were stolen from the synagogue in the course of the great pogrom of 1664.

For many years the Nachmanowicz synagogue remained a center of culture and learning for the local Jews. The name of the famous Jewish scholar David Ha-Levi Segal, one of the most prominent commentators of ritual code of Yozef Caro, and author of the famous work “Ture Zahav,” as well as the names of prominent rabbis, including Zwi Aschkenazy, Haim Rappoport, Leib Bernstein and Yakob Ornstein are associated with the synagogue. In the late eighteenth century a small porch was added to the synagogue from the side of the courtyard, with a Hebrew inscription over the entrance: “Our teacher and rabbi David Ha-Levi prayed here.” The synagogue eventually came to be known as Turei Zahav (The Golden Lines), after the name of Ha-Levi's work. Later Turei Zahav became Rejza Zahav – the Golden Rose. This name went rather well with the legend about Yitzhak ben Nachman's daughter-in-law.

Until 1801, the Nachmanowicz synagogue functioned as the main synagogue of the city. After construction of a new Great synagogue, the «Golden Rose» diminished in importance, never regaining its former significance, until it was destroyed.

Over the course of its existence the synagogue underwent many changes to its original look. Older elements were removed in numerous renovations, while new ones were added to fit the demands of the times. For example, the attic was reconstructed in the eighteenth century. By 1863 the synagogue was in an unsatisfactory condtion; according to the conclusions of the Construction Committee of the Municipal Council, a number of deficiencies needed to be removed. In particular, renovation of the stairs leading to the women's galleries and a new ceiling under the galleries in the porch section were required. However, these repairs were not undertaken at the time. In the early twentieth century, the Minor City Synagogue was ill suited to serve as a House of Prayer, both in its exterior and in its interior. According to local historian Franciszek Jaworski, the synagogue known as Turei Zahav was

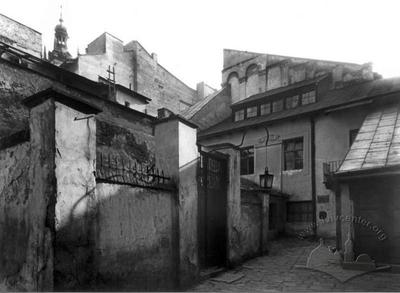

«obstructed by the walls of the shabby buildings of Blacharska and Zaarsenalna Streets, among the dirty lanes of the Jewish quarter… To see the synagogue one ha[d] to pass through the gate of the building…, look into the courtyard and be disappointed by the look of a mean-looking backyard building with a porch, whose external appearance neiteher reveal[ed] its ancient origins, nor the beauty of its interior. And truly, only once inside, [was] the artist and the architet seized by a sense of wonder when looking at the cruciform gothic arch-roofs, built with late-Renaissance detail and the original construction of the stone altar, built in the form of a portal. This curious and, at the same time, rare artefact of ancient Lwów architecture is at odds with its surroundtings to such an extent that inadvertently it creates the feeling of a pearl, hidden… in the garbage-heap». (Jaworski F. Złota Róża // Tydzień. Dodatek do Kurjera Lwowskiego. – Lwów, 1902. – N 32. – S. 502).

Thus, the synagogue was in dire need of renovation. In the early twentieth century its measurements were taken by local architect Michal Kowalczuk, who proposed to reconstruct the synagogue in its original 1595 appearance. It was necessary to renovate the women's section of the synagogue, which failed to meet elementary security requirements, as it could be accessed only through single, very narrow stairs. Nevertheless, the community intended to have the synagogue completely renovated, motivating their intention with the fact that the synagogue was the most valuable historic landmark of the Jewish community in the city.

Fundraising was organized in 1912-1913, and in 1914 the synagogue's board, headed by Abram Korkis and Mark Rohatyn, ordered to dismount the stairs, which were by then about to collapse. On their own initiative, without agreeing their actions with the Conservation Society and the City Council, the community also dismounted the original 1595 arch-roofs in the porch, as well as the arch-roofs of the side galleries. The new arch-roofs were not appropriate to the building. The city authorities ordered a stop the renovation and demanded that a project be submitted for approval before the workd could continue. A committee consisting of engineer Henryk Salwer and architect Leopold Reis, as well as government commisars Jakób (Yakub) Diamand and Dawyd (David) Maschler), and community leaders Korkes and Menkes, concluded that the synagogue's condition was satisfactory, but that the old arch-roofs should be reinstalled. The invited architects Salwer and Reis proposed two possible solutions. Reis's project envisioned two fire exits with stairs leading into the street in the northern and southern walls behind the altar. The project also envisioned the opening of a door leading to the porch in the western wall. Engineer Salwer proposed to widen the existing western entrance, explaining that the creation of two entrances (from the north and south, as Reis suggested) would limit the available space of the women's section, and allow for even fewer seats. The eighteenth-century porch was taken apart according to Reis's project just before the start of the First World War and, at the same time, the restoration work started, led by Salwer and under the supervision of Rabbi Osia Hescheles (Osiah Hesheles). Electric lighting of the synagogue was provided by the Electra company owned by engineer T. Balko and associates (T. Balk&co). The renovation work was interrupted by the Russian occupation of Lviv in 1914-1915. However, contracts with various repairmen were signed by late 1915. Reconstruction of two stone columns and capitols, as well as clearing of the arcades and stone columns above the heads of the first-store pillars were agreed upon with mason Wojciech Jabłoński. Numerous complications and delays arose because of the war. Funds were scarce. In one instance, the community promised to pay after the war (this was the case with the photofixation, performed by Volodymyr Pidhorodetskyi (Wlodzimierz Podhorodecki) on January 14, 1915. In 1917, the master-mason (carver) Aloiz Traversa reconstructed the two columns, widening the foundation and replacing stones that had crumbled under one of them.

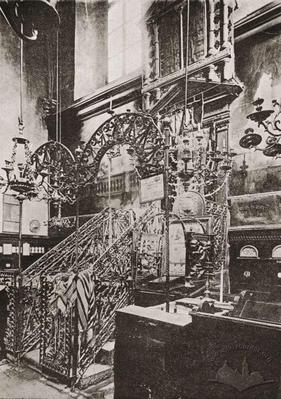

In 1918 the Conservation Society joined the renovation, proposing to reconstruct the building in its original appearance, restoring among other things the attic with cornices, and lowering the roof above the galleries to reveal the gothic western windows of the prayer hall. The society stressed the need to involve renowned architects in the process. However, after a competition was held and won by Jozef (Yosef) Avin, the synagogue community continued the renovation based on the earlier project by Reis. 1921 saw the reconstruction of the old dismounted arch-roofs (from a mixture of lime and cement), and the repairs of the walls, the strengthening of the columns was completed by replacing their hexagonal section by a rectangular one with concrete bases. After these renovations the synagogue was rather more modest in appearance, having lost many of the elements of décor – thus, among other things, all the wall-paintings were plastered over, and the whitestone borders of the windows were destroyed. The requisite repairs were far from completed even when, on June 26, 1934 the synagogue was proclaimed a national (all-Polish) monument of Renaissance architecture. The interior of the synagogue also remained modest, while several valuable architectural elements remained, such as

“the mizrach on the eastern wall, an artfully decorated beam with a forged grate, a large seven-shoulder chandelier, funded by Dr. Menahem de Jona in 1690, several artistic chandeliers, reflecting tin-plates, a donation-box and a water basin by the entrance, as well as the so-called Chair of Elijah for the circumcision ceremony. (Schall J. Przewodnik po zabytkach żydowskich Lwowa. – Lwów, 1935).

In august 1941 the synagogue was completely robbed of its reliquaries, and in 1943 it was demolished by the Nazis. The explosion brought down the ceiling of the prayer-hall, as well as the southern wall and galleries adjacent to it.

In 1943 Janusz Witwicki took the measurements of the remaining ruins and designed a reconstruction project. His project envisioned a high attic with a crown of props and volutes for the synagogue. A model of this project now remains on a plastic panorama by Witwicki, today in Wrocław, Poland.

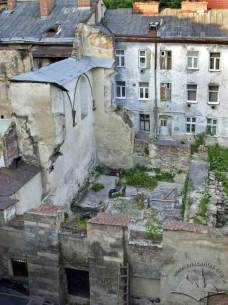

In the Soviet period the building lay in ruins. Attempts by the municipal authorities to conserve the ruin in 1988-1989 only brought further harm. The bases of the “Tuscany” columns were hewn apart, while the stone borders of the beam and the stair by the niche of Aron Ha-Kodesh were broken. The remains of the original floor were dismounted at the same time. The remaining northern wall, along with fragments of the eastern and western prayer-hall walls, and a part of the western wall of the porch were conserved. The original Renaissance portal from 1595 and the eighteenth-century doors remain standing from the side of the courtyard, which is accessible through a passageway leading from the house No. 27 on today’s Fedorova Street. The main façade of building No. 27, constructed in 1913 displays a memorial plaque to David Ha-Levi. The idea of reconstructing the Golden Rose was embodied in a project by architect Serhii Kravtsov, which recreates the synagogue as of the early seventeenth century. In 2007, archaeological research led by Yurii Lukomskyi discovered remnants of elements of the whitestone construction, and revealed the foundations of the western stone of the synagogue (dating from the eighteenth century), as well as wooden bits of the burnt treadmill.

Architecture

The Golden Rose synagogue was constructed as a fortified building, as it stood next to the city walls. The synagogue's thick walls were built of brick and stone, and the building topped by a high Renaissance attic. The attic was decorated with “blind” arcs with bay-windows and concluded in a crown of props and volutes. The floor of a synagogue was customarily positioned several steps below ground level. The women's galleries were on the second level of the porch and southern wing. The stairway into the galleries was on the outside, by the western façade. All the walls of the buiding displayed high prolonged bay-windows trimmed with whitestone borders. The entrance into the synagogue lay “through a low door to the low-ceilinged part. Three arcs between the pillars which supported the women's gallery and the western wall, created a frame that served as the background for the synagogue proper.” (Schall J. Przewodnik po zabytkach żydowskich Lwowa. – Lwów, 1935).The prayer hall was covered with two sections of a gothic ceiling on stone ribs with five headstones.

The square beam with rounded corners stood in the middle of the prayer hall and was disproportionally large. Stairs led to it from the north and south sides. The arrangement of the interior was centered around Aron haKodesh (altar closet), situated in the middle of the eastern wall. The closet had the appearance of a Renaissance portal with a triangular fronton, richly decorated with whitestone carvings with stylized plant and ornamental motifs. Stone sacrifice postaments with sand for the candles stood on either side of the Aron haKodesh, while the walls were decorated with flower pots in Classicist style. A pulpit for the cantor stood next to the altar. The beam and the Aron haKodesh were richly decorated with forged metallic elements. The walls were covered with traditional paintings with Hebrew inscriptions and a plant ornament. The synagogue was rich in its interior splendor, which included silver chandeliers, caporets, menoras, etc. The southern corner of the porch, adjacent to the prayer hall, held the eternal flame, the Ner Tomid. The left side of the remaining whitestone portal of the main entrance has a marble donation-box (significantly damaged) with a Hebrew inscription, consisting of the acronym MARI. Today the synagogue is in ruins – only parts of the northern, western and eastern walls, as well as the foundations of the beam and the portal of the main entrance remain.

Related buildings and spaces

People

Józef Awin

– (1883, Lviv — 1942,

Lviv, Yanivsky concentration camp) was an engineer, architect, restorer,

photographer, graphic artist, painter and watercolorist, historian and theorist

of art, collector.

Awin won a contest for the best reconstruction project of the Golden Rose synagogue after WWI.

Zwi Ashkenazy – renowned Rabbi of the TaZ synagogue («Golden Rose»)Leib Bernstein – Rabbi of the TaZ synagogue

David Ha-Levi Segal – Rabbi of the synagogue, one of the most renowned commentators of the ritual code of Joseph Caro, author of the famous «Ture Zahav».

Isaac – a local Jewish painter, possibly an author of the paintings of the synagogue

Isaak Nachmanowicz, Yitzhak ben Nachman – founder of the synagogue, owner of the land, local merchant, senior member of the Kahal, President of the Jewish Diety in Lublin in 1589, chief financier of the Polish King Stefan Batory.

Wojciech Jabłoński – master mason who reconstructed two stone columns and capitols, and was also responsible for clearing the arcades and stone columns above the capitols of the first-floor pillars.

Jan z Sienny – owner of the so-called Olesko plot of land, which he received as a gift from the Polish king in the mid-fifteenth century, and where the Golden Rose synagogue was constructed.

Korkes and Menkes – synagogue community leadersMenachem Margolioth (1740-1801) – spiritual teacher, Rabbi of the TaZ synagogue

Mordechay ben Yitzhak (Marko Isakowicz), Nachman ben Yitzhak (Nachman Isakowicz) - sons of Isaak Nachmanowicz, patrons of the synagogue.

Yakob Ornstein (Jakob Orenstein) – Rabbi of the TaZ synagogue

Włodzimierz Podhorodecki (Volodymyr Pidhorodetskyi) – architect who performed the photofixation of the synagogue in 1915.

Ambroży Przychylny, (real name Ambrosio Nutclauss), Adam Pokora (de Larto) and Henryk Salwer – architects and engineers who restored the synagogue.

Zachary Sprawny (Zaccary de Lugano) – master masons, who built the synagogue in 1565 under Szczęśliwy.

Paweł Szczęśliwy (Pavlo Schaslyvyi) – architect who designed the synagogue.

Haim (Chaim) Rappoport – Rabbi of the TaZ synagogue

Leopold Reiss – architect who performed repairs and restoration works.Aloiz Traversa – master mason (carver). In 1917 he reconstructed two columns, widening the foundation under one of them and replacing the crumbled stones.

Sources

- Центральний державний історичний архів України у Львові, ф. 701: Юдейська громада Львова, оп. 3, спр. 333, спр. 683.

- Александрович В. Руїни синагоги «Золота Рожа». Історична довідка // Архів інституту Укрзахідпроектреставрація, спр. Л-37/3.

- Бойко О. Будівництво синагог в Україні // Вісник ін-ту Укрзахідпроект-реставрація. – Львів, 1998. – Ч. 9.

- Бойко О. Синагоги Львова. – Львів, 2008.

- Вуйцик В. Львів – місто европейське // Вісник інституту Укрзахідпроектреставрація. – Львів, 2004. – Ч. 14. – С. 182-184.

- Груневег М. Найдавніший історичний опис Львова // Жовтень. – Львів, 1980. № 10.

- Долинська М. Львів: простір і мешканці. – Львів, 2005

- Зіморович Б. Потрійний Львів. – Львів, 2002.

- Зубрицький Д. Хроніка міста Львова. – Львів, 2006.

- Історія Львова в документах і матеріалах. – Київ, 1986.

- Каталог синагог // Вісник інституту Укрзахідпроектреставрація. – Львів, 1998. – Ч. 9. – С. 90-95.

- Капраль М. Привілеї національних громад міста Львова XIX-XVIII ст. Львів, 2000.

- Кравцов С. Синагоги Західної України: стан і проблеми вивчення // Вісник ін-ту Укрзахідпроектреставрація. – Львів, 1994. – Ч. 2. – С. 12

- Могитич Р. Планувальна структура львівського середмістя і проблеми його датування // Записки наукового товариства імені Т. Шевченка. Праці секції мистецтвознавства. – Т. CCXXVII. – Львів, 1994.

- Bałaban M. Żydzi lwowscy na przełomie XVI i XVII wieku. – Lwów, 1906.

- Bałaban M. Dzielnica żydowska: jej dzieje i zabytki // Biblioteka Lwowska. – Warszawa, 1990. – T. III.

- Grotte A. Deutsche, böhmische und polnische Synagogentypen vom XI bis Anfang des XIX Jahrhunderts. – Berlin, 1915.

- Janusz B. Przewodnik po Lwowie. – Lwów, 1922. – S. 37.

- Jaworski F. Złota Róża // Tydzień. Dodatek do Kurjera Lwowskiego. – Lwów, 1902. – N 32. – S. 502.

- Księga przychodów i rozchodów miasta 1404-1414 / Wyd. A. Czołowski // Pomniki dziejowe Lwowa z archiwum miasta. – T. II. – Lwów, 1896.

- Kravtsov S. Turei Zahav Synagogue in Lviv // Bet Tfila. – Braunschweig-Jerusalem, 2006. – №2.

- Kravtsov S. Gothic Survival in Synagogue Architekture of Ruthenia, Podolia and Volhynia in the 17th-18th Centuries // Architectura. – Műnchen-Berlin, 2005. – №35;

- Kravtsov S. Turei Zahav Synagogue. L’viv, Ukraine. Digital reconstruction. – Jerusalem, 2006.

- Łoziński W. Patrycyjat i mieszczaństwo lwówskie. – Lwów, 1890.

- Schall J. Przewodnik po zabytkach żydowskich Lwowa. – Lwów, 1935.

- Zubrycki Sas J. Zabytki miasta Lwowa. – Lwów, 1928. – S. 2;