The Ossolineum and the First Exhibition of Antiquities in Lviv (1861) ID: 90

Story

Prehistory

In the 1830s-1850s, in the wake of romanticism, interest in the past and in ancient monuments began to slowly emerge in Lviv. Newspapers published articles that often related to architectural objects and encouraged readers to pay attention to the natural beauty of their native surroundings or contained ethnographic sketches. For example, a series of articles about Lviv churches prepared by Felicyan Łobeski and published in the weekly supplement of the Gazeta Lwowska became quite noticeable. Descriptions and images of Galicia's towns and localities were made by Bogusz Stęczyński, an amateur and traveller, who emphasized the sad and decayed condition of places with a once-glorious past, his publisher Kajetan Jabłoński adding that "we don't need to go to our neighbours for beautiful views" (Stęczyński, 1847). In the publications of Teodor Bilous, a teacher and later a Ruthenian deputy of the Galician Diet, one can see the disappointment and shame at the deplorable state of towns and villages, especially the folk architecture of the Ruthenians and their churches, which, he believed, should be replaced by strong and lasting architecture (Bilous, 1856). Along with local history sketches, pure inventions appeared sometimes in the Lwowianin, a newspaper published by amateur Ludwik Zieliński. After disapproving reviews by famous Polish scientists August Bielowski and Józef Kraszewski were published in Poznań and Wilno (now Vilnius) press, the periodical was closed (Charewiczowa, 1938, 54-58).

Exhibition's Idea

In that period, academic historians rarely turned to the study of material monuments, focusing on the study of written sources, such as chronicles. Among authors of this kind were Ruthenian historians Isydor Sharanevych and Vasyl Ilnytskyi, whose works, Ancient Lviv and Ancient Halych, respectively, were published in Lviv in 1861. Archaeological research, which would compare data from written sources and evidence of material objects or their remains, became a topic for discussions two decades later.

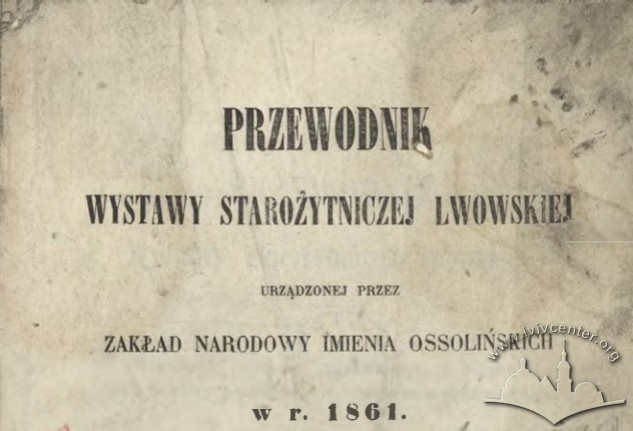

In the mid-19th century, there was no institution specifically dealing with heritage issues in Lviv. This task was decided to be undertaken by the Ossoliński National Institute, which had been operating since 1827 primarily as a library of Polish literature and a publishing house. In the spring of 1861, the director of the institution, August Bielowski, a historian and professor of the Franciscan University, announced that the first exhibition of antiquities would be held within its walls. In the announcement, he emphasized the importance of researching monuments of the past in a scientific way as the approach of local historians was unsystematic and often insufficiently critical.

It was assumed that private collectors would send monuments and art objects to the institution, Ossolineum employees would help to professionally describe them and compile a catalogue, and visitors would have a rare opportunity to see things that were otherwise inaccessible to the public, closed, for example, in the palaces of aristocrats. After the end of the exhibition, all objects had to be returned to their owners. This approach was borrowed from similar exhibitions held in Warsaw (1856) and Kraków (1859).

It was declared that the exhibition had charitable, scientific and national aims. "Such a grouping of national monuments... will refresh and complement the image of the ages in the memory... and will prove to strangers that we have not only virtues and national feelings, but also scientific respect for our past..." a newspaper reported after the first meeting of the exhibition committee in January 1861. The scientific and national issues were closely intertwined in it; Polish heritage came to the fore, and the history of the region was presented in inseparable unity with other parts of the divided Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. "The role of Lviv is... to complement Polish exhibitions with the topic of Red Ruthenia" (Czytelnia dla młodzieży, 1861, Nr. 23, pp. 181-183).

Among the organizers of the Lviv exhibition were several persons from the Ossolineum, who later collaborated with the conservator of monuments Mieczysław Potocki — in particular, Fr. Ivan Stupnytskyi and Kazimierz Stadnicki. Józef Lepkowski, a leading archaeologist from Kraków and co-organizer of the exhibition held there in 1859, was invited for consultation. Since he was unable to participate, Karol Rogawski, who also worked on the Kraków exhibition, arrived instead. An aristocrat (count) from the village of Olpiny near Tarnów and a revolutionary who took part in the 1846 events, he was an amateur archaeologist and a member of the State Council in Vienna. In 1863, Rogawski was appointed a conservator of monuments; later he had an important part in the founding of the National Museum in Kraków. Therefore, for Lviv residents, the Scientific Society in Kraków was a clear reference point, several organizers of the Lviv exhibition being its members or correspondents.

The organizers hoped that the exhibition would cause a stir and contribute to the development of interest in monuments of the past. They tried to attract visitors from the widest possible circles, as the opening hours and the entrance fee indicate. The exhibition was open every day and without weekends in the afternoon hours (3-7 p.m.), thus allowing employees to see it. On Sundays, the entry to the exhibition was the cheapest (10 kreuzers against 30 on other days), potentially attracting those who would not normally attend such events at all, for example, workers or maids. It was planned that someone from the organizing committee would be present at the exposition every day to tell those interested about the objects on display and provide explanations. The morning hours on Wednesdays were reserved as a time for visiting scholars, when the director and custodian of the Institute's stocks were present. On that day, the entrance fee was 1 gulden (Głos, 1861, nr. 91, p. 4). Moreover, the organizers hoped that the exhibition in Lviv would be an occasion for interested persons from afar to visit the city.

Although the organizers openly referred to the Kraków and Warsaw exhibitions in their statements, they did not mention any other similar exhibitions within the Austrian Empire. In 1861, several significant events took place in the empire: first of all, the Art and Archaeological Exhibition of the Society of Antiquities (Alterthumsverein) in Vienna. All crown lands of the empire, including Galicia, were called to take part. A small number of exhibits, mainly archaeological finds, were sent to the exhibition by the Ruthenian National House, an institution that became fully operational only later. No one else from Lviv took part. In the Central Commission for the Protection of Monuments, this non-participation was explained by the holding of the Third Exhibition of Polish Antiquities in Lviv, mentioning in the same context the insignificant involvement of Hungary, which was also planning its exhibition in Pest in the spring of 1861. Lviv did not mention Vienna, and Vienna in a similar way mentioned Lviv with only one word (Mittheilungen, 1861, Heft 1, pp. 21-22). In Lviv newspapers, one can come across only an exhibition of antiquities in Paris mentioned, with a note that a similar one was planned in Lviv (Głos, 1861, Nr. 15, p. 4).

The exhibition was located in the left wing of the Ossolineum building, in five rooms on the first floor. Each room contained different types of monuments. In the first one, manuscripts, diplomas, seals, numismatics, etc. could be seen. In the second room, there were Turkish tents and carpets, żupans of hetmans Stanisław Żółkiewski and Stefan Czarniecki, sabers and belts, gold and silver objects, furniture from the property of Polish kings and "famous men."

In the third room, there were church items, while the fourth one contained a collection of arms, provided to a large extent by the magistrate and by the military commandant's office in Lviv, and other things. In the fifth room, paintings and archaeological finds were placed (Dziennik literacki, 1861, Nr. 34, p. 276).

Reviews

The result of the exhibition, as one of the Lviv reviewers wrote, did not justify the expectations, although it became a significant event for the city’s intellectual milieu. Among the reasons cited was a low response from collectors, as well as communication problems: at the time of this event, Lviv did not yet have a railway connection, which prevented the participation of people from outside the city. The way the objects were displayed was criticized, it was mentioned that no artist or photographer took pictures or photos of the exhibition; the catalogue was inconvenient to use as well.

"I have already seen [similar exhibitions] in France, England and Germany... and they only remind us how poor we are," wrote an anonymous columnist, using the common argument of those times that Lviv and the region were poor in monuments. Among a number of other remarks, he also noted the feeling of discomfort caused in him as a visitor by the glorification of historical heroes and generally considered the focus on the past to be inappropriate. "While we work in the sweat of our brows to revive the living, they resurrect the dead. The grave air blows to me from there, while I want to live and spread life around me" (Głos, Nr. 117, pp. 1-2).

Another extensive review in a little-known Lviv newspaper emphasized the special position of Poland compared to other countries in the West. Allegedly, it was this that determined the different nature of the exhibition, the ultimate need to attract wide circles of the population and the seriousness of the attitude to the past (which was not entertainment). It also highlighted the Lviv magistrate's participation in the exhibition and the closedness of the Town and County Records (pol. Akta grodzkie i ziemskie) archive, which was under the care of the Austrian government and did not participate. The importance of attracting collectors from outside the city to the Lviv exhibition was explained by the fact that "...local collections are too small, because in ancient times Ruthenia was like a phoenix, constantly reborn from the ashes and fires, and in recent times the largest preserved collection went under the [state] monopoly" (Czytelnia dla młodzieży, 1861, Nr. 23, pp. 181-183).

Among Ruthenian (Ukrainian) scholars, who also took part in the preparation of the exhibition, were Isydor Sharanevych and Vasyl Ilnytskyi, a professor of history at the gymnasium and its director, who had collaborated with the Ossolineum for a long time. Fr. Ivan Stupnytskyi, chancellor of the Greek Catholic Church, a collector and a numismatist, known among Lviv residents as a supporter of the idea of Polish-Ukrainian cooperation, later a long-term vice-marshal of the Galician Diet, also participated.

One of the few Ukrainian newspapers published in Lviv at that time, the Russophile Slovo, did not publish news about the exhibition. This periodical rarely commented on matters of cultural life, focusing instead on news from the Galician Diet and the State Council, publishing speeches by Ruthenian politicians and articles from the province about the injustices suffered by the Ruthenians of that time, as well as reports concerning the language. In 1861, it continued to condemn the positions taken towards the Ruthenians by Polish papers, the Głos and the Przęgląd powszechny, which were the chief periodicals reporting on the exhibition. Only at the end of the year, a few months after the exposition was closed, the Slovo published a feuilleton entitled "Antiquity." The text had a direct reference to the exhibition only in the first sentence and was written in Aesopian language about the Polish institution abusing Ruthenian history, similar things going on since time immemorial and leaving the Ruthenians (Ukrainians) with the possibility of only minimal participation in a subordinate position (Slovo, Nr. 87, pp. 429-431).

After the exhibition

After the exhibition was over, in 1862-1863, the Ossolineum had a card catalogue of its library collections designed and a larger and more comfortable reading room space arranged. The vacated premises were turned into a museum for antiquities, whose concept was drawn up by Wincenty Pol and Fr. Ivan Stupnytskyi. On this occasion, in October 1864, Pol read a report on the monuments of Lviv in the Ossolineum and emphasized the need for their institutional protection. In his opinion, such an institution could be municipal and this responsibility should be taken on by the City Council. As a successful example, he cited the City Archive that was "exemplarily organized by our esteemed friend Jan Wagilewicz" at that time (Pol, 1865, 390). He emphasized the need to establish permanent institutions on a number of other occasions, including when delivering popular lectures in Lviv on various topics like history of literature in 1864-1865.

The conservator Mieczysław Potocki, who, coming to Lviv from his estate in Kotsiubynchyky, had an opportunity to hear Wincenty Pol's report, took it as a basis for his further work, as well as the list of Lviv objects Pol compiled, considering these valuable monuments. Having chosen objects for restoration, he invited Pol and Stupnytsky to help him in these matters; according to his proposal, the Central Commission nominated them the Commission's correspondents. It is possible that during this visit he also got to know the future conservator of monuments, Karol Rogawski; his correspondence with the latter at the turn of 1865 reveals interesting details and personal motivations of the conservator regarding his work. In the following year, 1865, it was in the Ossolineum that Potocki reported on his first achievements in the protection of monuments.

* * *

The Ossolineum never became a monument protection institution, but the exhibition held there provided an impetus in this direction. The need for such an institution in Lviv, whether in the form of a society or in the form of a government service, was discussed within its walls and in its environment in the 1860s. From the very beginning, there was a clear focus on the unity of the once divided lands of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the dominance of the Polish view on the history of the city and the region, the national and scientific aspects being closely intertwined.

People

Sources

- Центральний державний історичний архів України у Львові (ЦДІАЛ), 130/1/821. Перелік предметів, надісланих Народним домом на виставку старожитностей у Відні, 1860

- Okolice Galicyi Macieja Bogusza Stęczyńskiego, (Lwów: Nakładem Kajetana Jablońskiego, 1847)

- "Sprawozdanie z czynności zakładu narodowego imienia Ossolińskich, czytane na posiedzeniu publicznem dnia 17 października 1861 r. przez zastępcę kuratora Maurycego hr. Dzieduszyckiego", Biblioteka Ossolińskich, t. I, 1862, s. 392-403

- "Sprawozdanie z czynności zakładu narodowego imienia Ossolińskich, czytane na posiedzeniu publicznem dnia 12 października 1864 roku przez Maurycego hr. Dzieduszyckiego kuratora-zastępcę", Biblioteka Ossolińskich, t. VI, 1865, s. 381-393

- "Przemówienie Wincentego Pola na posiedzeniu w zakładzie nar. im. Ossolińskich dnia 12 października 1864 roku", Biblioteka Ossolińskich, t. VII, 1865, s. 389-396

- "Sprawozdanie Mieczysława Potockiego, konserwatora budowli i pomników wschodniej Galicyi", Biblioteka Ossolińskich, t. VIII, 1865, s. 342-377

- θеодоръ Бѣлоусъ, Древнія зданія въ справненіи съ ньінѣшними, (Львовъ: Въ печатнѣ Ставропигійской, 1856)

- "Wystawa starożytności ojczystych we Lwowie", Biblioteka Warszawska, 1861, t. III, s. 690-698

- "Wystawa starożytnicza we Lwowie", Czytelnia dla młodzieży, 1861, Nr. 23, s. 181-183

- August Bielowski, "Przewodnik", Dziennik literacki, 1861, Nr. 34, s. 276

- "Odezwa Kuratorji literackiej Zakładu narodowego imienia Ossolińskich", Dziennik literacki, 1860, Nr. 99, s. 791

- "Kronika", Głos, 1861, Nr. 11, s. 4

- "Kronika", Głos, 1861, Nr. 15, s. 4

- "Kronika", Głos, 1861, Nr. 91, s. 4

- "Listy wnuka do dziada, II. Lwów dnia 16. maja", Głos, Nr. 117, s. 1-2

- "Kronika", Głos, 1861, Nr. 119, s. 3

- Karl Weiss, "Die kunstarchäologische Ausstellung des Wiener Alterthumvereines", Mittheilungen der k.k Central-Commission für Erforschung und Erhaltung der Baudenkmale, 1861, Heft 1, s. 21-22

- "Korrespondencya Tygodnika illustrowanego z Galicyi", Tygodnik illustrowany, 1861, Nr. 107,

- "Kronika", Przegląd powszechny, 1861, Nr. 57, s.3

- И., "Древность", Слово, 1861, Nr. 87, с. 429-431

- Łucja Charewiczowa, Historiografia i miłośnictwo Lwowa, (Lwów, 1938)

- Bernard Kalicki, Przewodnik wystawy starożytniczej lwowskiej urządzonej przez Zakład Narodowy imienia Ossolińskich w r. 1861, (Lwów, 1861) https://rcin.org.pl/dlibra/doccontent?id=132574

- Joanna Paprocka-Gajek, "Wystawa starożytności" z roku 1856 w pałacu hrabiostwa Potockich, Muzeum Pałacu Króla Jana III w Wilanowie, https://www.wilanow-palac.pl/wystawa_starozytnosci_z_roku_1856_w_palacu_hrabiostwa_potockich.html

- Наталя Булик, "До питання про формування археологічної науки в Галичині у ХІХ столітті", Матеріали і дослідження з археології Прикарпаття і Волині, Вип. 9, (Львів, 2005)