During World War II, more than 5 million Red Army soldiers were taken prisoners by the Germans, 3.5 million of whom died. Over 1.3 million people were killed or driven to death in POW camps in occupied Ukraine. This means that Soviet prisoners of war were the second largest category of victims of the Nazi regime after the Jews. Violence against them and the Holocaust were closely linked also due to the fact that the Jews present among them also had to be identified and shot. Sometimes such executions took place directly on the battlefield. In fact, Jewish Red Army soldiers can be considered one of the first victims of the Holocaust.

In Lviv, the center of Nazi violence against Soviet prisoners of war was the so-called Citadel, a fortification complex where Austro-Hungarian, Ukrainian, Polish and Soviet garrisons were stationed alternately. From June 30, 1941, this territory was occupied by the German military and in July it began to be used to keep Soviet prisoners of war. Initially, the front assembly point number 18 was located there and, later, a stationary camp for privates and sergeants — the Stalag 328. The commandant of the latter was Major Blut. The territory of the Citadel was surrounded by a 2.5-meter-high wooden fence, on top of which 4 rows of barbed wire were stretched. Nevertheless, residents of the streets adjacent to the Citadel could see what was happening there from the windows of their homes. Many Lviv residents witnessed columns of exhausted prisoners of war escorted through the city streets from the railway station to the Citadel. So, as in the case of the Holocaust, it was a form of undisguised public violence.

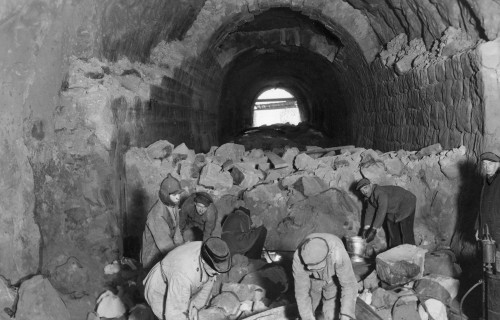

All buildings in the Stalag area were surrounded by two rows of barbed wire 3.5 m high, so the movement of the prisoners was limited. Until the autumn of 1941, they were kept in the open air, and then began to be transferred to the barracks. Starvation, consequences of injuries, unsanitary conditions, spread of infectious diseases led to high mortality rate. Many went crazy over the lack of food as they had to eat leaves and bark from trees and to catch cats and dogs accidentally wandering into the territory of the Citadel; in search of something edible they rummaged in piles of garbage. The typhus epidemic in the autumn of 1941 claimed several hundred lives every day. Virtually no medical care was available, although there was an infirmary in the Stalag. Another reserve infirmary, where patients were sent, was located in the former convent of St. Macrina. However, the lack of medicine made the prospects of those who were taken there hopeless. The dead were taken out and buried at the Janowska cemetery. Attempts by Lviv residents to help prisoners of war, for example through the Ukrainian Red Cross system, had minimal consequences and were often blocked by the Nazis.

Work teams composed of prisoners of war were engaged in various kinds of forced labour in the city. For any routine violation prisoners were punished by beating or execution. At the same time, the Nazis tried to recruit them to the so-called "eastern" formations of the Wehrmacht, turning the prospect of starvation into an attractive incentive to enrol in the service of the Nazis. A camp police of about 60 people, led by former Red Army officer Andrey Yakushev, was formed in the barracks from among the prisoners of war. The police differed from the rest of the prisoners by their blue-painted uniform and armbands with the letter "P" (i.e. Polizei — police). They lived in privileged conditions, were given better food and were able to visit brothels, therefore becoming a reliable tool for maintaining a brutal regime.

From each new group of prisoners of war that arrived at the Stalag, officers, political workers, and Jews were selected, who were kept for some time in even worse conditions and later were shot dead in the Lysynychi forest on the outskirts of Lviv. At the same time, Jews were kept separately, in the so-called dungeon, punishment cell in the basement of the barracks, while the others were kept in the "tower of death", as it was called by the prisoners themselves. There they were not provided with food at all and were kept half-naked even in the cold season. Even the camp police avoided going to the "tower of death" because there was a constant stench there, given the lack of toilets and the ban on letting out those who were kept in it. When several hundred people (there are indications that about 300 at a time) were gathered there, they were transported by trucks to the place of mass killing.

According to postwar Soviet estimates, 284,000 prisoners of war passed through the Stalag in 1941-1944, half of them died. Obviously, these data are greatly exaggerated. It is known that the planned adaptation of the Citadel buildings to accommodate 12,000 prisoners of war was not implemented. Therefore, they were designed for a maximum of 10,000 people. According to Colonel Felix Henker, who commanded all the POW camps in the District of Galicia from September 1941, 8,000 people were kept there at the same time. The number of prisoners of war was constantly changing and depended, among other things, on the situation at the front. As of April 1942, there were 2,900 people there, 1,500 in June and 5,600 in August, when prisoners of war began to arrive from the so-called Barvinkove pocket. Due to the lack of statistics for the entire period of the Stalag operation, it is impossible to specify the number of its victims at this stage of research.

Most of the survivors were later sent to camps in Germany. From 1942, French and Belgian prisoners of war were kept in the Stalag, as well as Italians from 1943. The conditions of their detention were much more tolerable, and the Soviet prisoners of war had even to serve them, for example, as porters.

In Soviet times, the territory of the Citadel was in no way memorialized, although such ideas did exist. They were intensified by a public trial of former camp police commander Yakushev, which took place in 1977 at a branch of the District Officers' House in Lviv. As a result, Yakushev was sentenced to death, the process being actively covered in the press.

Since 2007, the building of the former "tower of death" has been converted into a five-star hotel (Citadel Inn. Hotel & Resort). The owners of the hotel are trying to conceal the history of this place by installing a stone with the euphemistic inscription "In eternal memory of the event." The events of World War II are not mentioned at all in the "History" section of the hotel's website. In addition, the description of the hotel creates a romantic image of this place and emphasizes the refined style of the institution:

The Citadel was built not for the Lviv protection from outer enemy, but for the safety of the Austrian government and frightening the citizens.

Actually, Lviv Citadel was never used as intended.

You will be able to admire Lviv from the unusual perspective – in the retrospect of time, among the luxuriance of Austrian imperial style, in the midst of majestic views and medieval spirit.

Other facilities in the Citadel, including those where the camp barracks were located, warehouses, infirmaries, and others, are still used primarily for commercial purposes. The only reminder of the camp for Soviet prisoners of war, once situated there, is a memorial cross with the following inscription: "This cross was erected in memory of 140,000 soldiers belonging to the nations of Europe — Ukrainians, French, Poles, Russians, Italians, Jews, Belarusians, Belgians, who defended their homes and their countries and died here in the Nazi concentration camp "Stalag 328" in 1941-1944. May their memory live for ever!"